This article was produced with the support of Wärtsilä Energy

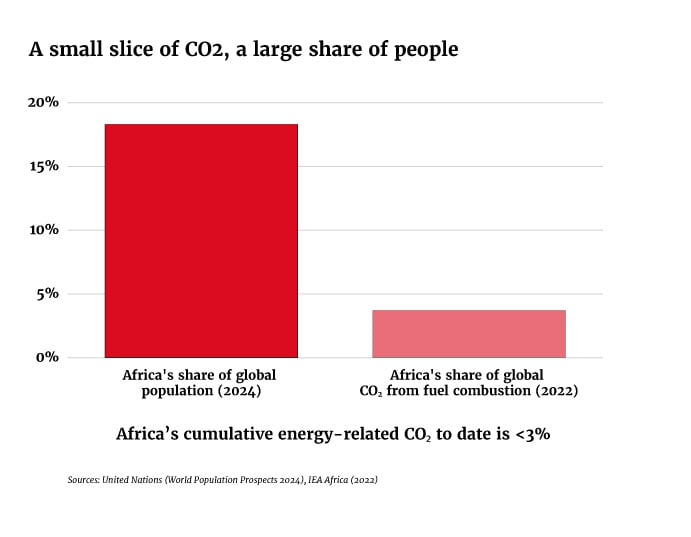

Africa is home to 17% of the world’s population yet produces only around 4% of global CO₂. On a per-capita basis, the continent emits roughly one tonne of CO₂ each year, the lowest of any continent. At the same time, Africa contains the world’s largest pocket of energy poverty. The critical question is not whether to reduce carbon, but how much temporary pollution can be tolerated on the path to energy prosperity, and under what conditions.

Reassessing an old question

Conventional thinking on energy has divided into two camps. One insists on zero fossil fuels, a moral stance that often clashes with fragile grids and frequent blackouts. The other advocates gas as the sole solution, appealing to funders but unfeasible in regions without gas infrastructure.

A more pragmatic approach is what I call lean carbon: a minimal, time-limited overdraft of emissions to secure reliable power now, under strict covenants that ensure an early peak and rapid decline. It is carbon on credit, a capped facility rather than an open-ended licence.

An old curve in a new context

The Environmental Kuznets Curve illustrates an upside-down U, showing how pollution rises at low incomes, peaks, and then declines as countries grow richer and introduce stronger regulations. Africa can achieve a lower and earlier peak than historic industrialisers because renewables are now cheaper, technology is more advanced, and coal can be largely avoided. The policy aim is to flatten the curve: accept a modest rise in emissions now to reach the downward slope sooner.

Reality, not dogma

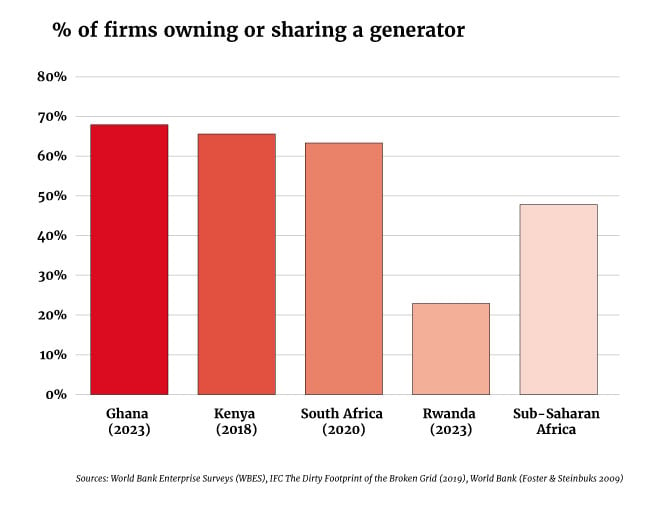

The present reality is not a continent neatly powered by wind and solar. Millions of diesel generators already hum in courtyards and factories because the grid is unreliable. Studies suggest that self-generation accounts for approximately 6% of installed capacity in sub-Saharan Africa, at a punishing cost of $0.30 to $0.70 per kWh, several times typical grid tariffs. When utilities fail, governments often lease emergency diesel in bulk, in some cases costing three to 4% of GDP. A clean statement in a strategy does not change the physics of a failing system.

Intermittent renewables alone cannot yet stabilise weak grids at scale. They require firm capacity, storage, or both. The sensible choice is planned, efficient firm power that complements solar and wind, rather than the messy reality of unplanned, dirtier backup generation.

The gas-only challenge

If fossil fuels are unavoidable, natural gas is preferable to oil products, producing fewer local pollutants and roughly half the CO₂ per kWh compared with coal. However, a gas-only strategy is unrealistic in much of Africa because pipelines and LNG infrastructure are scarce and markets are small. Outside a few corridors, such as the West African Gas Pipeline from Nigeria to Ghana and the line from Mozambique to South Africa, regional gas infrastructure is limited. Grand schemes to expand these networks have moved slowly, and most countries lack the demand density to finance pipelines or import terminals. Insisting on gas everywhere now often means no power at all.

Policymakers have improvised. Ghana, for example, plugged supply gaps with a floating power ship that initially ran on heavy fuel oil and later switched to domestic gas once supplies and connections were available. Senegal has commissioned heavy fuel oil-capable plants designed to convert to gas when new fields and pipelines come online. These are bridges intended to shorten the dirty phase, not invitations to lock in high emissions.

A workable lean-carbon pathway

A credible lean-carbon strategy is neither an immediate switch to all renewables nor a permanent reliance on gas. It requires three essential components.

First, new power plants must be able to switch fuels. Stations should start generating immediately using heavy fuel oil or diesel if necessary but be designed to transition easily to natural gas once it becomes available. Modern reciprocating engines, which can start and stop quickly, are ideal substitutes for solar and wind during periods of low generation.

Second, fossil fuel use must decline over time. These fuels should be deployed only when required, primarily for system stability or during renewable-scarce periods. Where fossil fuels are currently the only means of electricity generation, efforts should be made to decarbonise them systematically. This approach ensures that emissions per unit of GDP fall rapidly, even before absolute emissions peak. The priority is to displace diesel generators, which provide the dirtiest and most expensive kilowatt-hours on the continent.

Third, covenants must enforce compliance. To ensure the “carbon overdraft” remains limited and temporary, clear deadlines for switching to cleaner fuels, limits on total emissions, and power purchase agreements that reduce payments to conventional plants as renewables and storage expand are essential. Financing should focus on the entire energy system—renewables, backup power, and improved transmission—rather than individual plants.

Funders are adapting cautiously

Development financiers are shifting from blanket bans to conditional support for transitional projects. An increasing number argue that gas should be part of Africa’s just energy transition if integrated into national climate plans and structured to de-risk the shift to cleaner power. The most effective funding attracts private capital to entire systems, not stand-alone assets. Hybrid solutions that immediately reduce diesel use and accelerate renewable adoption are the priority.

Why a temporary rise in emissions is acceptable

Two points are critical for the climate ledger. First, Africa’s historical contribution is tiny. Sub-Saharan Africa, excluding South Africa, has emitted well under 1% of cumulative CO₂ since the industrial revolution; including South Africa, the figure remains below 2 per cent. Second, the opportunity cost of delay is enormous. Energy-starved economies grow more slowly, making future clean transitions harder to finance. A modest, time-bound rise to around 5% of global CO₂ as grids stabilise would still leave Africa’s share small, particularly if it displaces diesel generation and follows a clear plan to decline thereafter.

Managing risks

The primary risk is lock-in today’s temporary bridge could become tomorrow’s motorway. Contracts must include conversion deadlines and decommissioning triggers, require modular plants capable of switching fuels, and mandate transparent emissions dashboards. Stop-loss clauses should be in place if milestones are missed. Another risk is short-term cost minimisation, which may favour the lowest upfront tariff at the expense of reliability and integration costs. Procurement should focus on whole-system costs and carbon, not only cents per kWh.

Finally, while storage costs are falling, telling low-income countries to wait for cheaper batteries is not climate policy; it is deferring development. High capital costs already hamper clean projects. It is better to expand energy access with discipline, reduce diesel immediately, use growing demand to finance gas and storage, and retire fossil fuels on schedule.

The ask

For energy ministries and regulators: publish peak-and-pivot plans that indicate when emissions will peak and the mechanisms to reduce them. Integrate overdraft covenants into every firm-power tender. Allow dual-fuel plants where necessary, but mandate gas-ready design, switch-by dates, and emissions-intensity floors.

For development financiers and multilaterals: fund hybrid systems and grids rather than single-fuel projects. Reward early fuel conversion and managed retirement. Use guarantees to reduce the cost of capital for storage and transmission.

For developers and independent power producers: prioritise low-carbon firm power rather than short-term savings that create long-term lock-in.

Africa is not seeking permission to pollute; it is seeking permission to end energy poverty rapidly while ensuring emissions peak early. This is the lean-carbon bargain: a small, declining hump instead of a long, dirty plateau, and a faster path to the sunnier side of the Kuznets curve. Partners must help ensure the overdraft remains small and is repaid swiftly.

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google