In January this year, the world’s emerging artificial intelligence (AI) markets were rocked when Chinese company DeepSeek released a model they claimed to be significantly cheaper than the dominant US alternatives.

When announcing the launch of their “R1” model – an open-source large language model that works in a similar way to services such as ChatGPT – DeepSeek said they were able to train the model for just $6m, compared to the more than $100m US giant OpenAI spent producing ChatGPT-4. The massive cost savings were achieved because DeepSeek’s models require the use of far fewer advanced chips.

The news sparked a market rout on Wall Street, with investors fearing that major US tech firms could be undercut by cheaper rivals in China. Concerns over the future demand and value of advanced ships saw the American chipmaking giant Nvidia shed almost $600bn in market value on a single trading day – the biggest single-day loss in US history.

New players hailed

In Africa, however, many greeted the news with much more enthusiasm. After all, business leaders and policymakers are now largely united in recognising the potential of AI technology to drive up social and economic outcomes on the continent – or even to herald a period of leapfrogging in which Africa makes enormous developmental strides.

For example, AI tools are already being used on the continent to improve access to healthcare in rural areas, to help farmers achieve stronger crop yields, and to provide educational resources in areas with limited teachers.

But the main barrier to widespread adoption has been cost. As most African companies do not have their own AI-related infrastructure, they mostly have to rely on foreign cloud suppliers such as US-based Amazon Web Services (AWS).

These services allow companies to build and scale AI applications without having the advanced in-house computing that would otherwise be needed. However, African startups can find themselves paying monthly fees of $1,000 or more to access this, which is prohibitively expensive for most.

Kennedy Chengeta, an AI-focused entrepreneur and academic based in Pretoria, welcomed the DeepSeek news at the time. He told African Business that “cost has been one of the most significant barriers to AI adoption in Africa” and that “cheaper AI models like DeepSeek have the potential to dramatically reduce these costs.”

“By offering affordable, pre-trained models that require less computational power, DeepSeek enables businesses to adopt AI without the need for significant investment in infrastructure or talent,” he said.

Rashida Musa, CEO of AI integration firm rAlma, has noted that “young minds now have access to a low-cost opportunity to develop really ingenious solutions. [DeepSeek] is going to open the door to so many more bright minds to access this technology.”

The underlying numbers suggest a shift would hardly be surprising: DeepSeek costs just $0.27 to handle one million “input tokens” – the chunks of text users send to an AI model – and $1.10 to generate one million output tokens. By contrast, OpenAI’s GPT-4o models costs $5 and $15 respectively for the same tasks.

Threat of over-reliance

In some quarters, the increasing dominance of Chinese AI is raising hopes that Africa could stand to benefit from much cheaper access to potentially transformative technology. However, others are raising concerns that Beijing could leverage this as a way to exert its influence.

Akhil Bhardwaj, an associate professor at the University of Bath in the UK who studies the implications of AI adoption, argues that, from the Chinese government’s perspective, the proliferation of its AI technology “is a very smart way of increasing the likelihood that the government of another country will become beholden to you because you are just too important for their digital infrastructure.”

“There is a reason that the UK, for example, doesn’t outsource all of its manufacturing of vital aircraft components to China,” he says. “Even if they play in good faith, why would you put yourself in a position where you might be held hostage by a nation that has different sovereign interests to your own?”

Alberto Lemma, a research fellow and economist at the Overseas Development Institute in London, is similarly concerned about the power this potentially gives to Beijing.

“China has the luxury of not having to worry about election cycles and five-year terms, which means they always take a longer-term view,” Lemma tells African Business. “They aim for their commercial expansions to eventually allow them to influence the political structures of the countries in which they invest.”

Chinese firms proliferate

Lemma points out that Chinese companies are already investing relatively large sums to build data centres on the continent as a way of securing an early foothold in Africa’s AI market.

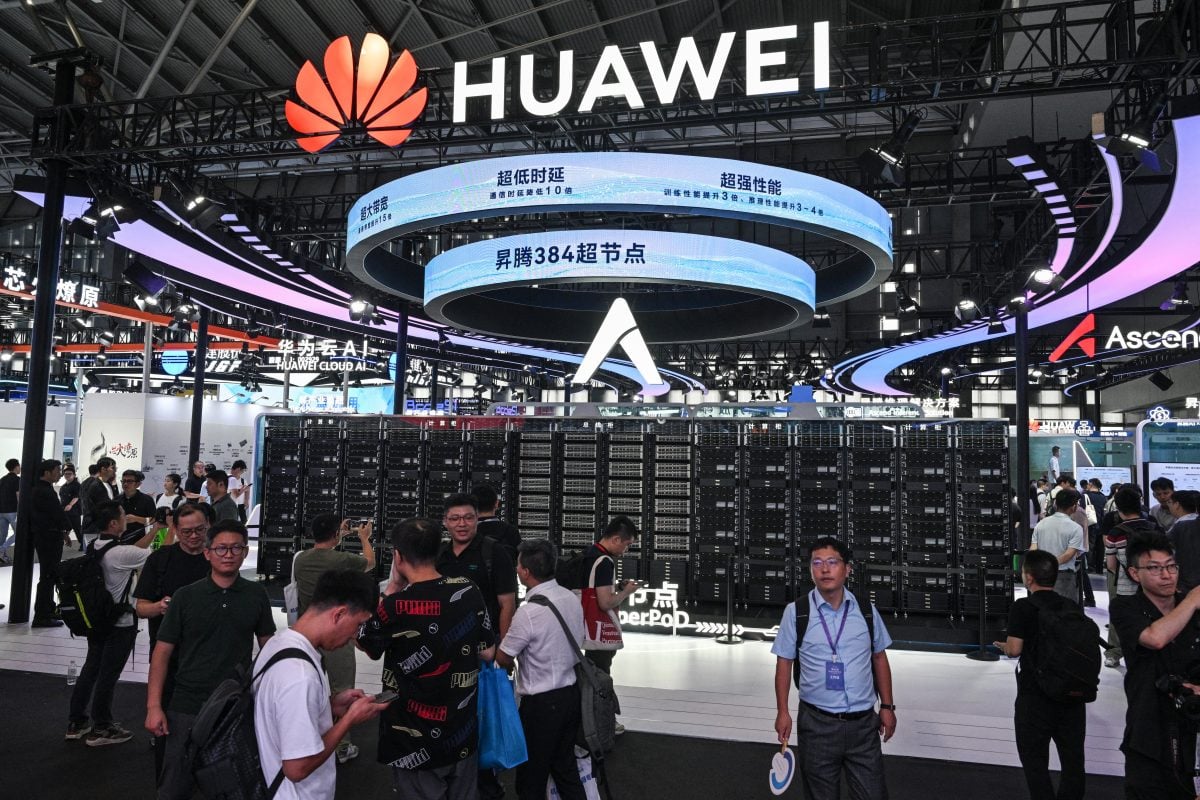

Telecommunications giant Huawei opened a data centre in South Africa in 2019, with the company saying its cloud business had grown “more than 16 times over” by 2024. In that year, it also became the first company to establish a cloud region in North Africa with the opening of premises in Egypt.

At the same time, it announced a new Arabic large language model alongside plans to invest $300m to further develop its AI capabilities in the Egyptian market. In total, Huawei plans to invest $430bn in North Africa as part of its “Intelligent Future” plan.

Meanwhile, Alibaba Group has also launched a data centre in Johannesburg, with further plans to invest in African AI infrastructure.

US firms have also made moves – last month, for example, Nvidia invested in pan-African Cassava Technologies to help expand its digital infrastructure – but their investments are not yet on the same scale.

Lemma tells African Business that “there are many different ways this control over infrastructure can be leveraged for geopolitical outcomes.”

“You can leverage infrastructure funding for political favouritism, but you can also leverage infrastructure funding to increase dependency on Chinese debt,” he adds.

“There is also another more speculative angle – but not so speculative as to make it unrealistic – which is the possibility of state-sponsored third-party actors using the information and data gathered through these kinds of investments to then influence different political outcomes.”

“Of course it is not just the case that African countries can be susceptible to this, but it is certainly a lot easier to get away with doing such things under the radar than elsewhere because there is less regulation and oversight,” Lemma says.

“There is also a vested interest for China to be able to influence geopolitical structures in Africa due to the large critical minerals reserves on the continent.”

For many African governments, these warnings are likely to sound overblown. A majority of African countries maintain friendly relations with China and – having long relied on Beijing to deliver cost-effective infrastructure projects like roads, ports and railways – are less likely than Western countries to see China as a geopolitical rival.

Africa is underrepresented in global AI

Another major incentive for powers such as China and the US to gain a foothold in Africa’s AI industry is the abundance of untapped data that exists on the continent. Africa currently represents just 2.5% of the global AI market and, as Lemma points out, the continent, which represents just under 20% of the global population, accounts for only around 5% of the global AI workforce.

This underrepresentation means that African data is distinctly lacking in current AI models – with the global consultancy firm McKinsey noting that “African data contributes little to AI model training due to historically unequal access and data collection.”

While this can often mean that existing AI technology is not sufficiently able to process African languages or make accurate decisions in a specifically African context, it also means that the continent is a source of untapped data that is increasingly valuable to the world’s major tech powers.

Bhardwaj tells African Business that “when you think about what is needed to power AI, what becomes clear is that data is the new gold. But where is new data going to come from?”

“It is going to come from places that have not produced much data before: places such as Africa.”

In some ways, the debate around which AI partners are most suitable for Africa are pre-emptive given most countries on the continent do not yet have sufficient infrastructure in places to harness this technology on a broad scale.

For many in Africa, the chance to access new technologies for the first time is likely to outweigh risks posited by experts based in Europe and the US.

Small African businesses are more likely to rue the ongoing lack of affordability of US AI platforms than fixate on the potential future dangers of embracing Chinese technology.

Nevertheless, Bhardwaj suggests a need for a more general caution, highlighting the need to Africa to shield itself from unnecessary economic and geopolitical risks across the board.

“There is too much fear of missing out – but this should not drive policy,” Bhardwaj says.

“People need to slow down and think about what AI actually means in practice. My advice to policymakers would be: do not think about AI can work for you, think about how this can fail, and let that be a starting point.”

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google