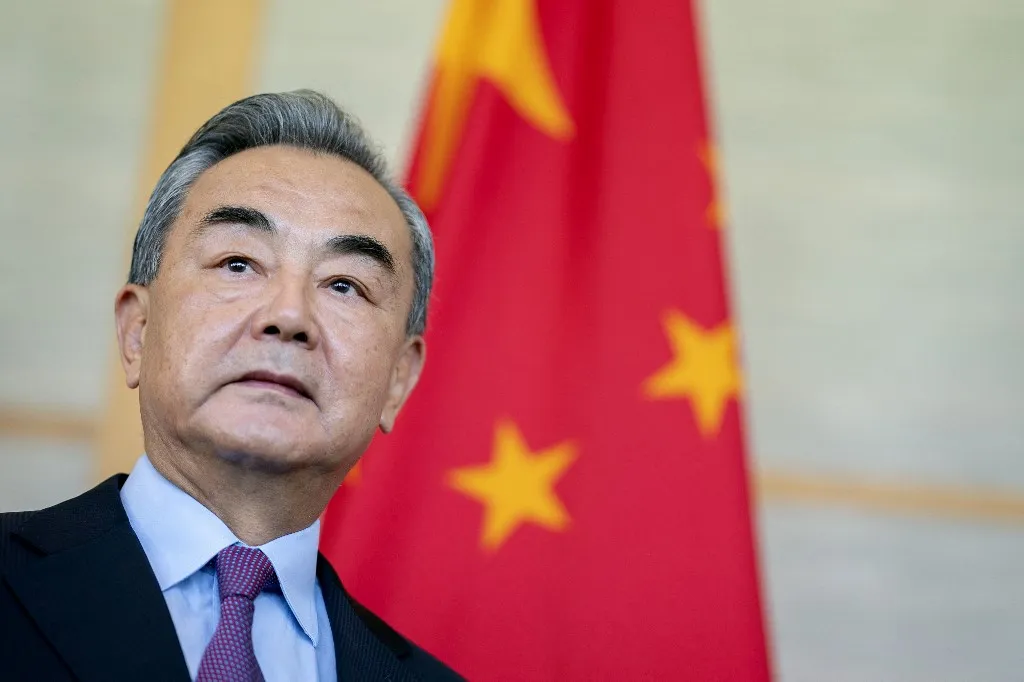

With African economies under severe strain from surging commodity prices and the tailwinds of Covid-19, hopes were high when Wang Yi, China’s top diplomat, took the stage for a major African debt announcement in August.

With a pomp not seen before in debt talks, Wang said Beijing had forgiven 23 interest-free loans to 17 African countries. He noted that the loans had matured, but remained tight-lipped about the total value and their recipients.

For cash-strapped African economies, many of whom count China as their largest bilateral creditor, the news that outstanding balances on Chinese government loans would be cancelled was well received. Around half of the continent is either in debt distress or at risk of it, with debt as a percentage of GDP worryingly high. All told, the world’s poorest countries – many of them in Africa – are facing $35bn in debt-service payments in 2022. Around 40% of that total is owed to China, according to the World Bank.

Interest-free loans vs interest bearing loans

However, while interest-free loan forgiveness could make a difference to Africa’s very poorest nations, it does not come as much of a surprise. In fact, no-interest loans make up a sliver of China’s lending to the continent. Some African governments even treat them as grants.

While the pageantry around the announcement could indicate an attempt by Beijing to tackle allegations of “debt-trap diplomacy”, analysts say it is unlikely to have an impact on China’s interest-bearing loans. And the current negotiations over Zambia’s debt obligations do not suggest Chinese banks are in a particularly forgiving mood.

Chinese lending to Africa peaked in 2016 at $29.5bn. By then it had already fuelled an infrastructure boom across the continent. As the leading external financier of infrastructure in Africa, Beijing built or upgraded 10,000km of railway, 100,000km of highway, 1,000 bridges and 100 ports, according to Chatham House, not to mention power plants, hospitals and schools. Kenya has Africa’s first urban expressway and a standard-gauge railway linking Nairobi and Mombasa thanks to Chinese credit.

Lauren Johnston, a professor at the University of Sydney’s China Studies Centre, says Chinese lending on the continent was initially underpinned by tumbling interest rates following the global financial crisis and a search for new markets, as well as a desire by Beijing to foster global development.

Today, she says, there’s a more immediate challenge in having to “manage a loan portfolio in the presence of global tensions and post-pandemic economic challenges.”

According to AidData, a research lab, interest-free loans account for less than 5% of the $843bn in Chinese loan commitments to 165 governments globally between 2000 and 2017. In the past two decades, China has written off at least $3.4bn of debt, almost all interest free loans to African countries, according to researchers from Johns Hopkins University.

They are considered part of China’s largesse in Africa, comparable to Beijing’s recent construction of Zimbabwe’s new parliament or a Lusaka’s state of the art conference centre, which came at no cost to either southern African country.

“Beijing has been doing debt write-offs of interest-free loans for 22 years,” says Deborah Brautigam, director of the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins. “These interest-free loans come from China’s central government budget and have already been completely accounted for, like grants and unlike bank loans.”

While the write-offs are not new, experts say the pomp around the announcement is, reflecting Beijing’s frustration with allegations of debt-trap diplomacy, particularly from the US.

Both the Trump and Biden administrations have accused Beijing of deliberately lending to countries it knows cannot meet their obligations for political leverage, for instance to prompt a vote in China’s favour at the United Nations General Assembly or smooth the way for a well-placed Chinese port. A 2020 State Department document warned directly of China’s “predatory development programme and debt-trap diplomacy.”

Beijing ‘irked’ by debt-trap allegations

Harry Verhoeven, senior researcher at Columbia University in New York, says the accusation does not hold water. In Djibouti, Uganda and South Sudan, which are often touted as possible debt trap victims, there is no evidence of Beijing making any such requests, he argues.

That has not stopped China from pushing to change the narrative. “It’s very clear that now, being on the receiving end of this kind of language for four or five years, Beijing is really quite irked by all of this,” Verhoeven says. “There is a felt need to push back and to actually show parts of African public opinion – perhaps even globally – that China is not the bogeyman the US and some of its Western allies are trying to make it out to be.”

During Kenya’s tense presidential election in August, winner William Ruto made Chinese debt a political football, vowing to publish secretive government contracts with Beijing and put an end to his predecessor’s excessive borrowing. Beyond the continent, Sri Lanka’s mounting public debt, some of it owed to China, led tens of thousands of Sri Lankans to storm the presidential palace in Colombo in July, perhaps worrying indebted African governments. Sri Lanka defaulted on its $47bn external debts last year.

Beijing dismisses the debt-trap claims as a hollow attempt by the US to reduce Chinese influence in Africa and boost its own. In August Wang condemned America’s “zero-sum Cold War mentality”.

While Hannah Ryder, chief executive of Development Reimagined, an African development consultancy in Beijing, has described interest-free loans as “the lowest-hanging fruit”, interest-bearing loans, which account for the vast majority of China’s lending, are quite another story.

Commercial loans can be restructured or reprofiled, but are almost never considered for cancellation, analysts say. Rather than coming through the government’s foreign aid programme, they go through China’s banks, which insist on being repaid. And with the Chinese economy stagnating somewhat compared to a decade ago, due in part to Beijing’s “zero-Covid” strategy, which shut down whole cities, that is unlikely to change.

“Chinese banks are reluctant to cancel or reduce the principal on bank loans inside China; doing this abroad would be unpopular among Chinese citizens,” says Brautigam. “Chinese banks want to be repaid in full.” In recent years China has reorientated its economy and is paying more attention to domestic and regional affairs. The boom times for African governments seeking Chinese loans appear to be over.

“Given the global economic winds that we see at the moment it’s important for Chinese lending institutions to be able to recoup much of the money they have made available to others,” says Verhoeven.“There was a time when China could just write off these things and say keep the change. Those days are over.” In fact, in the last couple of years Chinese lending to Africa has decreased significantly.

Johnston is open-minded about long-run prospects for debt relief. “Perhaps, far down the track [China] may offer debt relief,” she says, “[but] my sense is that China will first endure a long period of re-scheduling until ideally the loans are repaid.”

Zambia debt talks: a sign of things to come?

While expectations of write-downs or haircuts on interest-carrying loans are low, many see Zambia, which became the first African country to default on its debt during the coronavirus pandemic, as a vital test of how much debt relief China will be willing to stomach.

Most of Africa’s debts to China are owed by five countries – Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Zambia – some of whom are seeking to reduce their reliance on Chinese loans in the future.

Zambia owes roughly $17bn to a combination of multilateral lenders, commercial bondholders and sovereign creditors, and a third of it to China. The country is requesting $4.8bn in debt relief over the next three years. Debt restructuring is being handled through the Common Framework for Debt Treatments, set up in 2020 by the G20 cohort of wealthy countries.

Restructuring got off to a slow start, with some blaming China for the delay, which Beijing denies. Yet the second meeting resulted in a breakthrough commitment, allowing the International Monetary Fund to sign off on a $1.3bn lending programme. In July, Zambia’s finance ministry announced it was cancelling $2bn of undisbursed loans from external creditors, $1.6bn of them from Chinese banks.

China initially wanted to eschew the Common Framework altogether, Beijing’s ambassador to Zambia said in August, before a call between President Xi Jinping of China and President Hakainde Hichilema of Zambia convinced China to join the talks. Many have been surprised by China’s willingness to negotiate in the face of its first debt crisis.

Still, negotiations remain tense. Analysts say China favours extending maturities over write-downs, even though Zambia’s finance minister, Situmbeko Musokotwane, told journalists in September that “the choice between haircuts and stretching the repayment period… is a matter of negotiations.” He added that some creditors “will choose to have their money faster” while others would opt for repayment over a longer period.

While Zambia is a useful test case, Verhoeven is wary of extrapolating it to the rest of the continent. “Zambia is pretty exceptional in terms of the composition of its debt, its important role as a copper producer, its history of defaults,” he says. “Zambia is not representative of the average African country and its debt profile, which is part of the reason I think why China has been willing to be, by Chinese standards, quite generous.”

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google