It was impossible not to see the irony last Thursday, when the Africa pavilion in COP30’s blue zone erupted in flames, sending delegates fleeing for their lives. Mercifully, no-one was seriously hurt. But as global temperatures rise, the sight of infernos ripping through parched landscapes is becoming all too familiar. The number of people exposed to wildfires has increased by 40% in the last 20 years, with 85% of those affected in Africa.

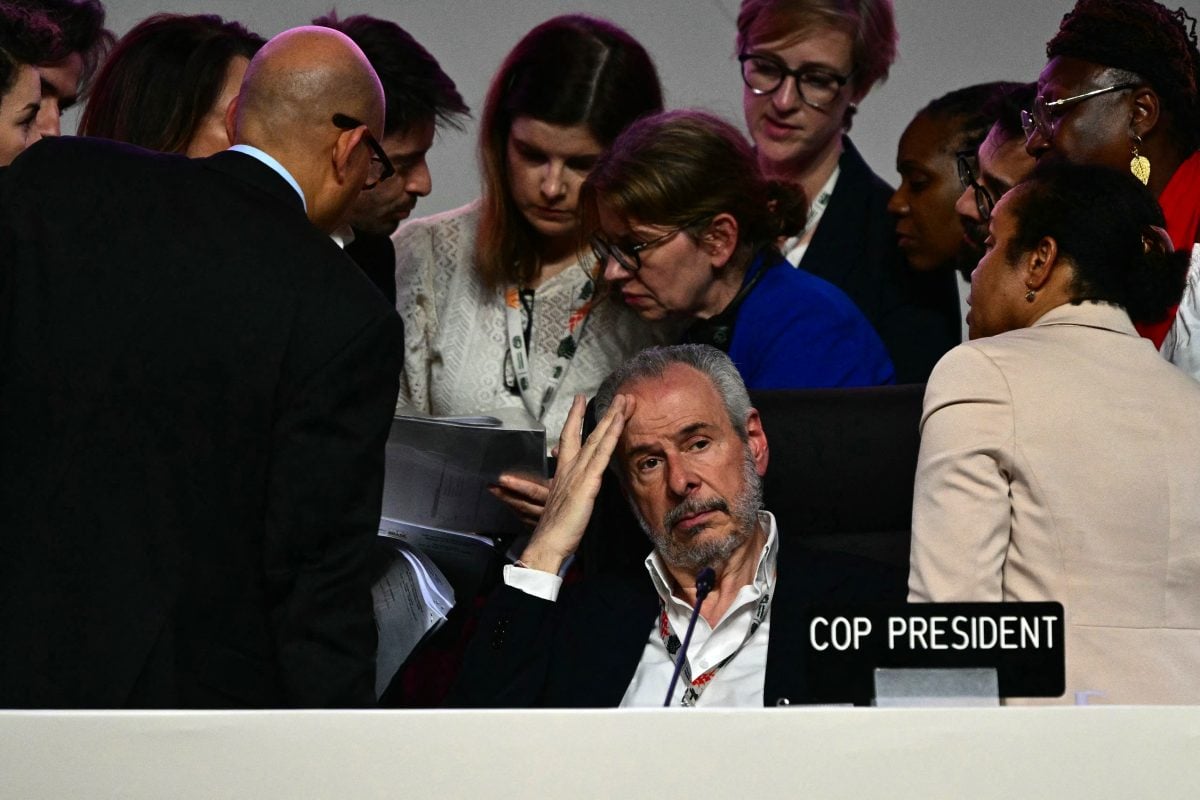

Over the course of two weeks of negotiations in the Brazilian city of Belém, the gods appeared to send multiple signs imploring global powerbrokers to take action on climate change. As well as the fire in the Africa pavilion, a biblical downpour briefly flooded the Pacific islands pavilion. Yet there is only modest evidence that negotiators got the message.

A series of familiar debates ended with familiar outcomes. Once again, the talks became bogged down in language on phasing out fossil fuels. Once again, promises on climate finance for the Global South are unaccompanied by a concrete plan for delivery.

There were, however, a handful of topics that became much more prominent at this year’s COP. In particular, the location of the talks in the Amazon focused minds on a threat affecting large parts of both South America and Africa – deforestation.

Frustration for forest finance

Brazil’s initiative to stem the loss of forest ecosystems – the Tropical Forests Forever Facility – was one of the key talking points heading into COP30.

The concept is based on both governments and private investors putting money into an investment fund. Some of the proceeds of this fund will then be used to reward countries that maintain low rates of deforestation and to support forest communities.

DR Congo and neighbouring countries that are carpeted by the Congo Basin Rainforest – the most important carbon sink on the Earth’s land surface, absorbing more carbon dioxide than even the Amazon rainforest – could be key beneficiaries of the TFFF. The non-profit TFFF Watch estimates DR Congo could net a maximum of $460m a year if the TFFF were fully operational and if it halted deforestation entirely.

However, commitments to the TFFF have been underwhelming. Brazil hopes to raise $125bn for the fund, and bringing COP30 to the Amazon provided a unique platform to solicit contributions. Just $6.7bn in pledges were announced before and during COP30, however, of which $3bn comes from Norway. The total pledges mean the TFFF is still far below the $25bn needed to bring the initiative into full-scale operation.

“I think there’s some degree of concern in terms of what we are seeing about the future of TFFF, especially when you look at the implications of not being able to secure the initial pledges,” says Tiago de Valladares Pacheco, Africa forest lead at The Nature Conservancy.

“There’s a cautious approach to it, which is not encouraging,” Pacheco adds, referring to the reticence of some governments to invest in TFFF. Without a significant ramp-up in contributions before next year’s COP, Pacheco fears the TFFF could prove to be a “missed opportunity”.

Glenn Bush, who leads a capacity-building initiative for protecting forests in DR Congo at the US-based Woodwell Climate Research Center, is somewhat more positive.

“I wish we’d had more. I wish we could raise the $25bn primary tranche,” he says. “But I’m actually very pleased that we’ve got the commitments.”

The TFFF did receive a boost towards the end of COP, when Germany – which had delayed a decision on investing in the fund – announced a $1.15bn contribution. Bush remains optimistic that the fund will help conserve Central Africa’s rainforests.

“This is an incredible opportunity, and it’s at a scale the like of which we’ve never seen before for conservation.”

A partial win on adaptation

COP30 was never expected to see a major breakthrough on setting new climate finance goals. That milestone came a year ago in Baku, when negotiators controversially agreed to a ‘new collective quantified goal on climate finance’ of $300bn a year by 2035. This is widely recognised to be only a fraction of what Global South countries need. The Baku text did, however, contain a vague reference to “scaling up” climate finance to the $1.3 trillion a year that developing countries say is required.

Over the past year, negotiators have been working on a “Baku to Belém Roadmap” that would provide a clearer path towards the $1.3 trillion figure. The roadmap was published shortly before the Belém talks began, but ultimately received little attention. The COP30 final text simply states that parties “take note” of the roadmap, without endorsing its approach.

More positively, COP30 was able to reach consensus on tripling finance for adaptation to climate change – a goal that Richard Muyungi, chair of the Africa Group of Negotiators, described as a “red line” for the continent during the final stages of negotiations.

Adaptation finance is one segment of climate finance; it focuses on helping countries to become more resilient to the impacts of climate change, for example by building sea walls to reduce the damage from coastal flooding. It is distinct from “mitigation” finance, which aims to lessen the extent of global warming, for example by replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy.

In the final deal, negotiators agreed to “call for” adaptation finance to “at least” triple by 2035. This only partially satisfied the Least Developed Countries group, which had sought a tripling by 2030. There is also some ambiguity about exactly what is being tripled, since no specific figure was included in the text. Extrapolating from the 2025 adaptation goal of $40bn produces a figure of $120bn a year.

“African countries, particularly the most vulnerable, made clear that COP30 needed to deliver resources for resilience,” says Lily Hartzell, senior policy adviser at think tank E3G. “And while the goal to triple adaptation finance by 2035 certainly represents a compromise, it is a concrete step to address their growing needs.”

Building on Belém

Catherine Koffman, Africa director for the UN-backed Green Climate Fund, tells African Business that COP30 saw “a movement towards accelerating implementation.”

“The days of doing pilots are gone,” she says.

“It’s all about platforms, country and regional platforms. And there were many that were actually announced at COP, there were many that were actually promoted at COP, because COP is seen as an opportunity to trigger that financial capital inflow.”

Koffman adds that African governments are increasingly recognising that the private sector will be part of the solution on climate finance.

“There was definitely an acknowledgement that we cannot reach these targets without engaging the private sector to make sure that we, from inception, are ideating and designing investment platforms that will be investable.”

She lists a number of “non-traditional” financial instruments that African countries could use to raise finance. As well as earnings revenues through the carbon markets, Koffman points to sustainability-linked bonds and loans, climate resilience bonds and “debt-for climate” swaps. The latter involve restructuring a country’s debt to reduce its debt servicing costs, in return for a commitment to use part of the savings to fund adaptation. Barbados became the first country to launch such an instrument in 2024.

While the direction of travel towards strengthening adaptation is a little clearer after COP, the path ahead is still shrouded in uncertainty. The need to get creative is a message certain to be heard more often in the years ahead.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google