In Freetown, Sierra Leone’s capital, the build-up of waste at hundreds of illegal dumpsites across the city appears never-ending. Piles of plastics and other rubbish clog waterways and wash-up on beaches, creating numerous health hazards, increasing the risk of flooding and threatening the livelihoods of the country’s fishermen. The open air burning of waste also releases various noxious gases.

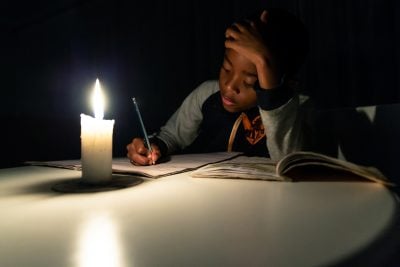

At the same time, Sierra Leone’s electricity supply is extremely fragile. Just 21% of households have access to power from the grid. Even the few that do have a connection enjoy only patchy access, since the country’s hydroelectric facilities struggle to generate power during the dry season. The government can barely afford an alternative supply from a floating power station operated by Turkish company Karpowership, which has turned off electricity on several occasions due to payments disputes.

The problem of having too much waste and not enough power appears to have an obvious solution: to generate electricity by burning waste.

Infrastructure development company Infinitum Energy is aiming to do exactly this in Freetown. It hopes to start work on a 30 MW waste-to-energy facility later this year, which is designed to generate power through incinerating 365,000 tonnes of waste annually.

“The big impact is going to be the reliability,” says Lindsay Nagle, Infinitum’s CEO, who points out that Freetown’s residents are lucky at present if they get more than a few hours of power each day. “We’re adding 40% more electricity to the grid,” he tells African Business, noting that the waste-to-energy facility will provide baseload power, rather than the intermittent supply that comes from solar panels.

Infinitum aims to have its facility operational by late 2027. But not everyone is convinced that waste-to-energy represents a good solution for Africa – and, despite a number of plans on the drawing board, progress has been very limited so far in making waste-to-energy a reality on the African continent.

A “monumental” opportunity?

Waste-to-energy is far from a new technology. Many European countries have been generating energy through burning waste for decades. In Sweden, 52% of waste is incinerated to generate energy in the form of both heat and electricity. Another 47% is recycled and just 1% is sent to landfill.[ii]

Yet Africa welcomed its first modern waste-to-energy infrastructure only in 2018, when the Reppie facility opened in Addis Ababa.

Several other African countries, as well as Sierra Leone, are also exploring waste-to-energy projects. In Lagos, for example, the state government signed a deal last year with Dutch company Harvest Waste Consortium to develop a waste-to-energy facility with a capacity of up to 75 MW. The state government has also signed a Memorandum of Understanding with cement giant Lafarge to use waste as a feedstock at one of the company’s production facilities.

Nagle is convinced that the time is ripe for Africa to harness the benefits of the technology. “We know waste-to-energy works,” he says.

Yet he does acknowledge some challenges. While Nagle says that “in an ideal world”, all Freetown’s waste would be diverted from dumpsites towards incineration facilities, he admits this won’t happen overnight. Currently, he says, only around 20-30% of the city’s waste is collected – the rest being simply dumped informally. Infinitum plans to pay nominal amounts to Freetown’s residents for collecting waste, which Nagle hopes will bring the collection rate to 60% when the plant starts operating, and then to 80-90% within five years.

Once this feedstock is sent to the waste-to-energy facility, the electricity generated at the plant is to be sold to the Electricity Distribution and Supply Authority, the state-owned utility, under a power-purchase agreement that is currently being finalised.

Nagle adds that there is “monumental” potential to expand waste-to-energy in other African cities, many of which suffer – to a greater or lesser extent – from similar waste and electricity access problems as Freetown.

“If I have my way, we are going to try and put two to three of these into development at various stages every year,” he says. “It’s going to be a wash, rinse, repeat business model.”

Burning question

Despite the apparent benefits from removing waste while generating much-needed electricity, many groups remain fiercely opposed to incinerating waste.

“It is not efficient, it is expensive, it’s economically not feasible, it’s polluting,” says Weyinmi Okotie, a clean energy campaigner at non-profit group GAIA Africa. Waste-to-energy plants release a “cocktail of noxious substances into the environment”, he adds.

One of the problems is that the technology “is not meant for Africa in the first place,” Okotie argues. He says incinerators are designed to handle “dry waste”, which makes up the vast bulk of waste in European countries where waste-to-energy is widespread. In most African countries, however, waste is dominated by organic material that does not burn well.

He warns that the Reppie facility in Addis Ababa has encountered a host of operational difficulties and is operating far below its planned capacity. Local media reported earlier this month that the city administration faces a compensation bill from the utility, Ethiopian Electric Power, after failing to meet its waste feedstock delivery quotas.[iii]

Okotie reserves his greatest fury for the argument that waste-to-energy represents a green source of power. “That’s one of the biggest lies I’ve ever heard in my life,” he says. “How can you say the burning of plastic, which is burning a fossil fuel, is a renewable source of energy? That’s crazy.”

This question is a matter of fierce debate worldwide. Advocates of waste-to-energy argue that diverting waste from landfill sites helps reduce emissions of methane, which is one of the most harmful greenhouse gases. Critics respond that there are better ways of dealing with the organic waste that releases methane, while pointing to data that burning plastics can release as much carbon dioxide emissions as burning coal.

Darron Johnson, regional head of Africa at Climate Fund Managers, an investment group that is helping to fund Infinitum’s project in Freetown, argues that emissions can at least be mitigated.

“The Freetown project will implement circulating fluidised bed technology, which significantly reduces pollutant emissions compared to conventional incineration methods. This technology is designed to comply fully with EU emissions standards,” he says. “Continuous emissions monitoring will be in place to guarantee adherence to these standards.”

Nagle also insists that a modern waste-to-energy will make a major improvement for Freetown. “The status quo is just horrific,” he says, pointing to a litany of health and environmental impacts arising from the city’s current lack of proper waste management infrastructure.

The debate on the merits of waste-to-energy shows few signs of being resolved. What is clear, however, is that Africa faces an increasingly severe problem if projections on increased plastic use prove accurate.

An OECD study published in 2022 estimates that plastic use will increase 6.5 times by 2060 in sub-Saharan Africa[iv] – creating an even more enormous waste management problem, for which all solutions are imperfect.

In this respect, Okotie welcomes efforts to reduce single-use plastics, such as the ban being implemented in Lagos State. “About 30 years ago, we had fine economies and beautiful lifestyles without so many single use plastics,” he says. “So first of all, we need to reduce the amount of plastic we are producing.”

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google