The World Bank’s board has voted to end a long-standing ban on funding for nuclear energy projects, potentially opening the door for several African countries to receive loans from the development lender.

Ajay Banga, the bank’s president, had been pushing the change since taking office in 2023 as part of his efforts to make ending energy poverty the key priority for the multilateral institution. The World Bank has overwhelmingly focused on financing solar and wind energy in recent years, along with other forms of renewable power.

“I think it’s an overdue move, but I’m glad that it’s happened,” says Todd Moss, executive director of the non-profit Energy for Growth Hub. “There’s really no logical reason to take a technology off the table before it can even be considered.”

The World Bank’s ban on funding nuclear energy was originally introduced in 2013, shortly after the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan, which led many developed countries to scale back their use of nuclear power. Japan itself closed all its reactors after Fukushima, but has since brought several back into use, after realising that ditching nuclear left the country dangerously dependent on imported fossil fuels.

Despite continued concerns over the massive cost and lengthy timelines for building nuclear power stations, interest in harnessing nuclear energy is growing both in developed markets and in many fast-growing middle-income countries.

Koeburg nuclear power station near Cape Town, built in the 1980s, currently hosts the only working reactors on the African continent. However, a new nuclear facility, built by Russian company Rosatom, is nearing completion in Egypt, while several other African countries are laying the groundwork for nuclear energy.

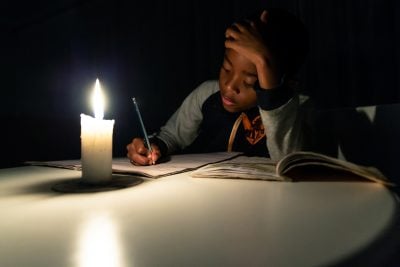

Energy for Growth lists Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia as the African countries that could be potentially viable markets for nuclear power by the 2030s. It says Rwanda and 12 other countries could be ready by 2050.

Catalysing investment

The International Finance Corporation – the World Bank’s private sector lending arm – will now remove nuclear energy from its investment exclusion list. Moss notes that one of the significant features of the decision is the impact it will have on other lenders.

Moss points out that at least 21 other agencies, including bilateral development finance institutions and regional development banks, along with some private investment institutions, had copied the IFC policy – and could now be poised to change course.

“We do think that now the World Bank has lifted its ban, many – not all, but many – of these other public agencies will also lift their bans,” says Moss. “I would expect some catalytic effect.”

The United States, the World Bank’s largest shareholder, had heavily pushed for the relaxation in the bank’s lending policies on nuclear energy. Support for nuclear energy is one of the few areas where there is a large degree of bipartisan consensus in US policy. This partly reflects how many of the companies developing small modular reactor technology – which could be better suited to many African countries that have relatively small energy markets – are based in the United States and are looking for export opportunities.

Oregon-based NuScale signed a preliminary deal with Ghana last year to deploy a SMR in the country.

Meanwhile, the World Bank’s board also discussed ending its restrictions on lending to upstream natural gas projects but was unable to reach agreement. Banga has also argued that producing natural gas should be considered in some circumstances as a way to provide energy access.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google