This article was produced with the support of Standard Bank Group

As countries deliberate on diversifying their energy mix to align with global trends on climate change, they have to find ways to build new value chains to address the negative impacts of the shift away from fossil fuels while simultaneously developing more resilient economies.

Managing the human story of the transition, which includes communities stranded when coal mines close, is key to getting buy in for a changing energy mix. Without this, the process may not be politically sustainable.

Climate change brings with it many challenges, but there are also opportunities that can be leveraged to build more resilient economies. Also needed are strategies to empower Africans to develop their own continent, including local content requirements and industrial policies to drive value addition of local resources.

The just energy transition will not be an easy journey in Africa, given the current dependence on coal, oil and gas in Africa, which accounts for up to 80% of current energy generation and, by some estimates, will continue to account for 60% of the energy mix by 2040.

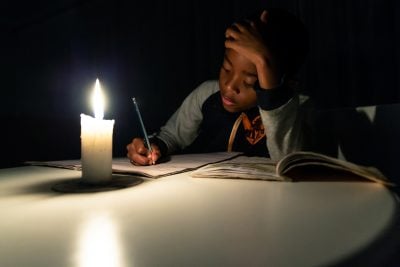

However, the shift to renewable energy in Africa is not just about reacting to international pressure but because it makes sense. It is helping to address the challenge of energy access that has seen up to half of Africa’s population without power and is allowing countries to generate cheaper energy. The cost of wind, solar and battery power has gone down by 80% over the past decade.

South Africa is a case in point.

At Standard Bank Group’s recent Climate Summit in Johannesburg, the Minister of Electricity and Energy, Kgosientsho Ramokgopa, said the country is increasing the share of renewable energy in its mix despite its strong competitive advantage in coal is because it makes sense, not because it is being pushed by western nations to do so.

It is also aware of the need to understand the socio-economic implications of the decisions it is taking. The decreasing cost of renewable energy is assisting the government to manage the affordability conundrum it faces to balance the need for the power utility, Eskom, to raise tariffs sufficiently to meet its obligation to keep the lights on but not so much that economic growth and poverty reduction efforts are undermined.

Competition presented by new players to entrenched state power monopolies is also helping to reduce the cost of power and foster innovation.

But African countries cannot, despite being under pressure to align their climate policies with those in western nations that aim to achieve net zero emissions, just walk away from their current natural endowments.

And funding is a challenge for current and proposed projects. Although climate funds are available, they are well below what is needed for African countries to even get close to net zero, and they are hard to access.

Africa is also out of step with the international focus on mitigation efforts prioritised by industrialised countries, which have contributed to most to emissions. Africa, which has contributed just 4% to global emissions due to its low levels of industrialisation, has prioritised adaptation measures to address its climate change challenges.

According to the Global centre on Adaptation, finance for this approach was only 36% of total climate finance in 2021-2022, and this was down from 39% in 2019-2020.

Key to bridging the funding gap is increasing the participation of the private sector in the energy transition. But a major constraint is the high cost of capital in Africa, as a result of international perceptions of high risk and other factors.

Faster reform of global financial architecture will reduce the cost of capital to ensure it better represents and serves developing countries, as will increasing available concessional finance, which currently represents just 16% of climate funding.

Energy strategies need to also take cognisance of the fact that each country has its own starting point in the transition journey. South Africa, for example, is in a very different place from most other nations, not just in its pursuit of diversified generation but also in relation to its strong financial base and deep capital market, for example.

It is also important that new projects are not just about access but about unlocking productive economic activity to maximise the impact of energy resources on growth.

Public private partnerships will help to improve the effectiveness of African countries’ nationally developed contributions (NDCs), commitments countries make to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions as part of climate change mitigation efforts.

Currently just 25% of NDCs have a developmental component and many lack regional plans. Updating of NDCs for submission in 2025 by signatories of the Paris Agreement gives countries a chance to review their policies, and perhaps place a greater focus on sustainable growth.

The scale of the climate change crisis makes a multistakeholder response imperative as countries in Africa look at their journey ahead to a just energy transition.

Watch the Summit discussions here: https://lnkd.in/dCXG_WVt

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google