This article was produced with the support of Standard Bank Group

The energy transition journey must not be something done for its own sake; we must ensure that the process drives social goals, upliftment and growth, said Luvuyo Masinda, Standard Bank Group’s Chief Executive of Corporate and Investment Banking, in his remarks at the Bank’s annual Climate Summit in Johannesburg on 1 October.

This ethos had to apply to each of Africa’s 54 countries, where all are coming from different starting points.

He pointed out that to achieve a sustainable and just energy transition would require a greater focus on development, building local value chains and extracting the greatest value out of natural endowments where they exist, while still meeting targets towards net zero in the fight against climate change.

“It is very clear this will require huge collective effort. We have gone beyond what is right and wrong to how to do it.”

The event, held in Johannesburg, is the fourth of its kind and one of the cornerstones of the Standard Bank Group’s sustainability strategy.

Transition must be locally just

Sim Tshabalala, Chief Executive of the Standard Bank Group, echoed Masinda’s remarks, saying that Africa was committed to the just energy transition, but it would not be sustainable unless it was “locally just – our communities will not allow it”.

“For Africa to achieve the best outcomes, a wide diversity of opinions and voices needs to be heard to influence the actions we take. And let’s not lose sight of all the opportunities of this transition as we move forward,” he said.

Dr Crispian Olver, executive director of South Africa’s Presidential Climate Commission, aligned his comments to the development debate, saying: “African countries need to see an equitable path to a local transition in a way that builds our value chains, benefits Africans and allows us to meet our targets. If not, the politics around these transitions will come unstuck.”

This includes moving towards a different energy mix where it makes sense, said South Africa’s minister of electricity and energy, Dr Kgosientsho Ramokgopa. He said the coal-dependent country is committed to an exponential increase in renewable energy sources.

“But we must do it, not under pressure from global powers, but because it is in our own interests. As we have the conversation about the just energy transition, we must understand the socio-economic implications of the decisions we are taking.”

Chairman of local power utility Eskom, Mteto Nyati, said “Let’s make sure we are aligned with the geography we are serving while also observing commitments we have made globally.”

Adedayo Olowoniyi, chief technical adviser to Nigeria’s power minister, weighed in on the issue of energy security, saying that every country must use its natural endowment for generation. In South Africa it is coal, in Nigeria it is gas, he said. “If we transition away from it, what happens to that value chain?”

Local content matters

Local content requirements can help to build local value chains, speakers said, but the process needs to be driven proactively and realistically in light of low levels of industrialisation and a deep dependence on imports, speakers said.

They also need to be viewed as regionally driven initiatives to lend scale to such plans and to justify the investment needed.

Funding was also a topic of keen interest at the summit, with speakers raising the challenges presented by the high cost of capital in Africa and in getting projects off the ground, particularly in countries dominated by fossil-fuel generation capacity.

Mark Swilling, co-director of the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, said: “Countries are wrestling with painful choices. These include whether to go slower on energy infrastructure to maximise local content or to go faster by importing what they need and bypassing the local economy.

“What kinds of investment requirements should we be thinking about to find that balance, that sweet spot?”

He said the reform of the global financial architecture is key to unlocking development in Africa’s energy sector by making more capital available to Africa, and at a cheaper cost.

Cost of capital

Most climate financing is debt, he said, with concessional finance being a small part of what is available. “Massive amounts of private sector capital are needed – but this won’t happen if the cost of capital does not come down.”

Between 2010 and 2020, Africa received just 2.4% of global renewable energy investments, and this was concentrated on investment grade countries in North Africa and Southern Africa. Funding is also a critical component of countries’ revision of their National Development Contributions in coming months and years as they react to pressure for a more diversified energy mix in their transition journeys.

Cristina Duarte, special adviser on Africa at the UN, said Africa had been put in a “green energy straight-jacket” by the global community.

“The international community is saying Africa must go green, but it is not providing the conditions.” It is also not recognising that Africa has a different starting point from other regions,” she said.

Also at issue is the fact that Africa is out of step with the global focus on mitigation to drive the energy transition. African countries need to build capacity to adjust to the consequences of climate change, which requires significant investment in adaptation strategies and infrastructure.

In terms of project funding in Africa, speakers mooted the benefits of blended financing to catalyse international capital, particularly where revenues are largely local currency funding. Having a strong balance sheet is also important, given the cost of capital in Africa.

Commercial banks have been responsive to energy reforms in Africa, but concerns remain about project pipelines to support sustainable investment, competitive tariffs, high risk perceptions and the low capital base of many countries.

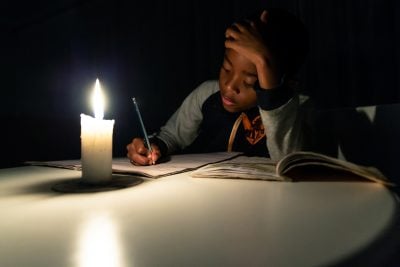

But banks are also supporting local development, said Rentia van Tonder, Head of Power at Standard Bank Group. “We don’t just focus on bankability and risk with our clients, but also look at the difference we can make to lives on the ground.”

“We encourage our clients to look at new projects that may address job losses that may emerge from the transition from fossil fuels, for example.”

A R250bn commitment

The Standard Bank Group has committed to mobilise a cumulative amount of R250bn in sustainable finance by the end of 2026. The Group has managed to reach R129.6bn of this funding so far and is well on track to meet its target.

It aims to achieve net-zero across its lending and investing activities by 2050, and in its direct operations by 2030 for newly-built facilities, and by 2040 for existing facilities.

“This summit is more than just a gathering; it’s a call to action that adds to our dedicated focus which we have lent to sustainability issues,” explains Masinda.

“As we confront the realities of climate change, we must ensure that Africa’s path to a low-carbon future is one that also promotes economic growth, energy access and social equity. Standard Bank is committed to leading this charge, leveraging our expertise, resources, and partnerships to support sustainable development across the continent through products such as green bonds, sustainability-linked loans, and specialised advisory services”.

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google