Political and business leaders across Africa have declared themselves ready to leverage the continent’s resources to boost energy access and facilitate green growth. However, this transition also presents challenges, including the need for substantial investment, infrastructure development, and ensuring equitable access to energy for all populations.

In the July edition of its Energy Series, African Business convened a panel of experts to discuss how African countries can navigate the challenges and take full advantage of the opportunities presented by the transition. The panel included John Leonard Mugerwa, Uganda’s deputy high commissioner to the United Kingdom; Caroline Kende-Robb, senior director of strategy and operational policies at the African Development Bank; Mike Sangster, senior vice president for Africa at TotalEnergies; Fola Fagbule, deputy director and head of financial advisory at the Africa Finance Corporation (AFC); and Adam Kendall, a partner at consultancy McKinsey and head of sustainability practices in Africa.

The discussion was moderated by Hannah Ryder, chief executive officer and founder of Development Reimagined.

Kendall set the stage by observing that the two main drivers that will have an impact on energy transition in Africa are economic and population growth. Economic growth is projected to be around 1.8% annually; the population of the continent is expected to double by 2050. Noting that “increasing energy access is incredibly important for economic development,” Kendall said a pathway to net zero must be integral to the continent’s energy expansion plans.

“Africa has a central role to play in helping the world achieve its net zero ambitions. The modelling we have done shows that without Africa, the world will not be able to get to a 2 degree pathway.” But Africa’s path to transition is hampered by limited capacity and insufficient, unreliable and weak grid networks. Its energy system is highly decentralised, with a high penetration of diesel.

“Everyone points out that Nigeria has an energy system of 4 GW or 5 GW but the reality is that when you look at the decentralised system, it’s somewhere between 40 GW and 60 GW.” This creates an opportunity that can also drive the transition. Africa is a prime market for low-cost renewable energy and has 7 of the 13 top countries with combined solar and wind capacity factors.

Africa also holds nearly 9% of the world’s gas reserves, which Kendall said can be utilised as a transition fuel.

Pointing out that lack of full flexibility in matching demand changes is a challenge for renewables, Kendall said a significant mix of on-grid and off-grid technologies will be needed, as well as a transition from diesel-based decentralised systems to renewable decentralised systems.

Uganda’s transition path

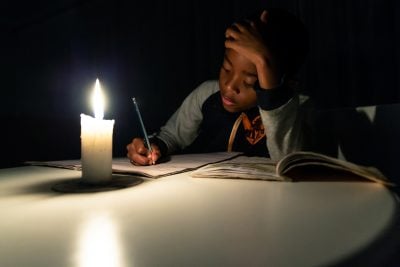

Mugerwa said Uganda was aiming for tenfold economic growth over the next 15 years to reach a target of $500bn. The country’s energy transition plan, finalised in 2023 with support from the International Energy Agency, aims to enhance access to affordable, clean energy in line with Goal 7 of the Sustainable Development Goals. He noted that 90% of Uganda’s current energy comes from renewable sources, such as hydropower and solar. However, only 20% of the population has access to electricity, with rural areas particularly underserved.

Uganda plans to increase its energy capacity from 1.5 GW to 52 GW by 2050. “The government is calling upon the regional development banks, the international financial institutions, and even the private sector,” Mugerwa said, emphasising the necessity for concessional financing to reduce energy prices for both domestic and industrial use.

To further diversify its energy mix, Uganda is exploring nuclear energy options in collaboration with the International Atomic Energy Agency and a South Korean firm. “We are hoping that in the next 6-7 years, we can have about 2 GW from the first nuclear energy plant.” This initiative, he stressed, aims to complement the existing renewable energy sources to meet the country’s growing energy demands.

Fair and just

Kende-Robb said a fair and just energy transition is what Africa needs, including a balanced energy mix that includes both renewables and transitional fuels such as gas to address the continent’s unique challenges and opportunities. “We recognise the need for an energy mix that includes everything,” she said, adding that, despite pressure from some quarters to avoid investing in fossil fuels entirely, “we can’t just change from where we are now to only investing in renewables, even though we have all the resources.”

Highlighting the African Development Bank’s commitment to renewable energy, Kende-Robb pointed out that from 2016 to 2022, the bank approved $8.3bn in energy commitments, with 85% directed towards renewable projects. These projects, including Light up Africa and the Desert to Power project, which aims to provide renewable energy to 250m people across 11 Sahel countries, exemplify the bank’s strategy to integrate Africa into the global economy and improve the quality of life for its people.

Renewable is practical

Fagbule argued that many, himself included, are adopting off-grid power solutions, including rooftop and home solar systems, out of practical need: “while I care about the environment, it is primarily an efficient solution.”

He pointed to AFC’s investments in Infinity Power, which currently operates 1.3 GW of renewable energy assets across multiple countries, with plans to expand to 10 GW by 2030. “Already, it is helping to avoid about 3m tonnes of carbon dioxide.” In Côte d’Ivoire energy access has dramatically increased from 10% to 94% of households in the last decade.

Transitional gas

Sangster also took the view that gas can be utilised as a transitional fuel. While renewable energy has, in the long term, a competitive edge, there are inherent challenges. “If you are going to invest in these large-scale plants and recover it over a 10 to 15 year period, there has to be some [regulatory] stability.” While conceding the challenges including power- buying monopolies, purchasing power of consumers, currency risks and erratic distribution networks, Sangster said Total is nevertheless investing in renewable energy projects on the continent. “We have five in operation in Africa at the moment, and more under construction. We are also looking at another 10-15 projects. We are also part of the project to bring power from Morocco to the UK.”

Responding to a question from the audience, Kende-Robb stressed the importance of adhering to the principles of COP21, particularly the concept of “common but differentiated responsibilities,” which recognises that countries will transition differently due to varying starting points, an approach meant to ensure that transitions do not exacerbate inequalities.

Fagbule noted that while the challenges to energy generation in Africa have long persisted, renewable energy solutions are one of the fastest-growing methods to overcome these issues, allowing for decentralised energy supply. “Ten years ago, we would have loved the opportunity that we have now to be invested in the largest renewable energy platform.”

Sangster pointed to the significant financing challenges associated with meeting Africa’s growing electricity demand: “If you want to have 100 GW, then it’s $100bn.” The Tilenga onshore oil project in Uganda had, he said, created up to 18,000 direct and 60,000 indirect jobs, along with training programs totalling 3m man-hours.

Concluding, Ambassador Mugerwa emphasised the need to recognise the principle of common but differentiated responsibility. While committed to the Paris Agreement and aiming for net zero by 2050, Mugerwa pointed out that without economic growth, the goal of achieving clean energy would be unattainable.

He noted that African countries, like Uganda, will still need oil and gas for the next 20 to 30 years. He cited the difficulties faced in financing the oil and gas pipeline project in Uganda, despite its importance for the country’s development, and called for multilateral financial institutions and the private sector to be realistic about supporting such projects.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google