In early December 2023 the Governor of the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) suggested that the East African country could be about to conclude terms for a $1bn loan from China. Kamau Thugge confirmed that “the National Treasury is engaged with the Chinese government” and noted that, should the cash arrive in time, the loan could be used to help pay off a $2bn Eurobond repayment that is due in June next year.

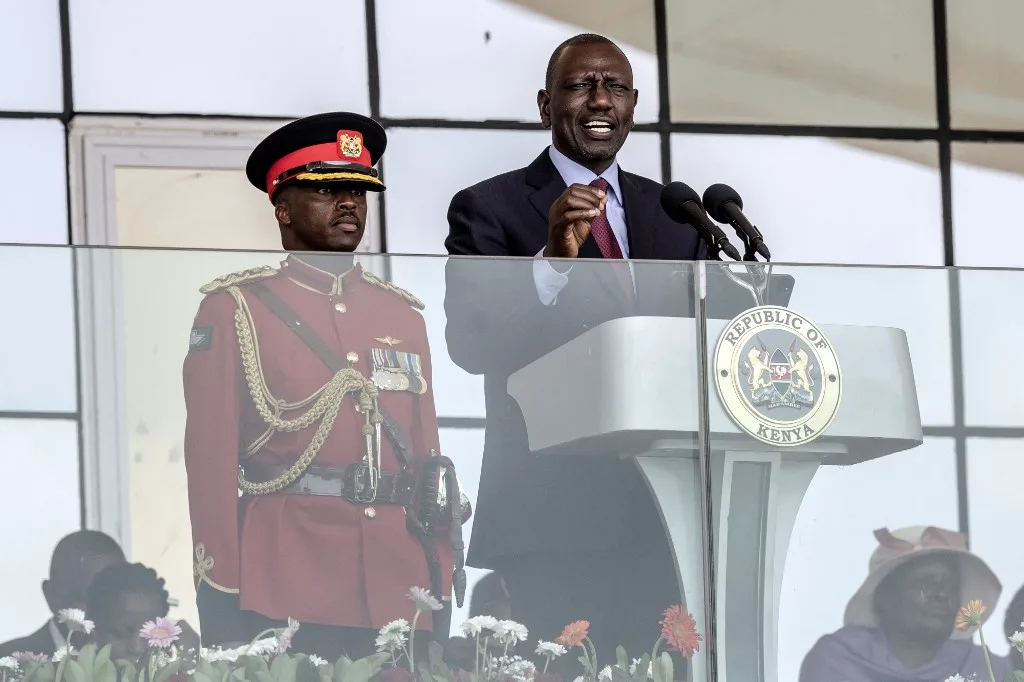

The move comes despite the President of Kenya, William Ruto, striking a hawkish tone on China during his election campaign in 2022, Ruto railed against the Chinese-financed loans agreed by his predecessor, Raila Odinga, which were used to fund a variety of infrastructure projects – but which Ruto blamed for contributing to Kenya’s large and growing pile of debt. The country’s debt currently stands at more than $70bn, around two-thirds of its gross domestic product.

During the campaign Ruto also promised to publish details of opaque government contracts with China, to deport Chinese nationals working in Kenya illegally, and to reduce Kenya’s dependence on Chinese loans.

Almost immediately after taking office, however, Ruto changed his tune on Kenya-China relations. At a meeting with Liu Yuxi, China’s special representative on African affairs, shortly after his inauguration, Ruto said “we cherish the robust friendship that Kenya enjoys with China.”

In October this year, Ruto also attended the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, where he opened talks on the potential $1bn loan and held discussions on debt restructuring plans.

Economic imperative

Fergus Kell, research analyst at the Chatham House Africa Programme in London, also tells African Business that “it should not be forgotten that, in his first term as deputy president from 2013 to 2017, Ruto was an active contributor to the Kenyatta administration’s turn towards China and the agreement of the major $5.3bn railway project loans that make up the dominant share of Chinese loans to Kenya.”

He adds that this development should not necessarily be seen as Kenya seeking to align itself with China geopolitically. “Any new lending is less about a decisive shift back towards China, and more of an acknowledgement of wider macroeconomic realities,” he says. “Kenya desperately needs financing to complete development projects and roll over existing loans but has effectively been locked out from international bond markets.”

Jared Osoro, an economist based in Nairobi, also rejects the idea that Ruto is seeking to initiate a geopolitical shift and argues instead that the loan is “an economic imperative”.

“As far as the management of public debt is concerned, the Kenyan government cannot afford the luxury of choosing” who its creditors are, Osoro says. “It is a question of whether the government can access resources in a manner that supports Kenya’s recovery programme and helps Kenya avoid the debt distress situations seen in other African countries such as Ethiopia, Ghana, and Zambia.”

Renewed focus on China

While some analysts believe the fresh $1bn loan is crucial if Kenya is to repay the maturing Eurobond next year and avoid defaulting, the move is likely to bring China’s activities on the continent into renewed focus. Critics have often suggested that Beijing is engaged in “debt trap diplomacy” in Africa and elsewhere – a strategy alleged to involve luring countries such as Kenya into unsustainable levels of debt so that China can seize strategic infrastructure when the debtors fall into economic difficulties.

Edward Howell, a lecturer in East Asian politics at the University of Oxford, tells African Business that “the threat of facing uncontrollable, swelling levels of public debt seems insufficient to deter Kenya from accepting Chinese money” and is concerned about how Beijing may seek to benefit from Nairobi’s financial dependence.

“China remains Kenya’s largest trading partner, despite growing domestic concerns of Chinese economic coercion, as well as espionage in the form of cyberattacks, as we saw earlier this year,” Howell says.

However, Kell believes that “the debt trap narrative is oversimplistic” and notes that “state assets such as Mombasa Port have not been offered as collateral for Chinese loans.”

“China is Kenya’s largest bilateral external creditor, but its lending is well below that of multilateral institutions. Chinese loans were one part of a rapid increase in borrowing under the Kenyatta administration, which also included taking on major commercial debt, such as both Eurobonds and costly syndicated loans,” Kell points out.

The looming Eurobond

“Chinese loans are a significant contributing factor [to Kenya’s debt struggles] but not solely responsible – the dominant source of default risk has been a $2bn Eurobond that is maturing in mid-2024,” he says.

Putting aside the political argument over which creditors Kenya should be relying on, Osoro believes that the critical issue from an economic perspective is how Kenya’s debt is structured.

“The main concern to my mind is not necessarily the amount of debt that Kenya is taking on, but the structure of that debt,” Osoro tells African Business. “Over the past ten years or so, we have seen the average tenor of Kenyan loans narrowing. This means that right now the government is borrowing on the very short market, where interest rates are higher than the central bank rate.”

Osoro adds that this structure is not only more expensive for Kenya’s authorities, but also has the added impact of discouraging the banking sector from lending to the private sector. Given that banks can achieve higher yields by lending money to the government through short-term loans, there is little incentive to offer capital to business, further stunting economic growth in Kenya.

In the short term, the $1bn loan from China should be sufficient to ensure that Kenya meets its upcoming debt repayments and avoids defaulting on its liabilities. Advocates of the current administration would argue that this is a significant achievement in an environment around the world in which weaker national currencies, a stronger US dollar, and higher interest rates have made it more difficult for emerging market economies to service their debt.

In the longer term, however, there is clearly a need for the Kenyan government to formulate policies that will help reduce the country’s dependence on external creditors and allow Nairobi to start paying down its existing debt pile. This may prove to be tricky in practice, given Ruto’s commitment to high-spending projects such as the Financial Inclusion Fund consumer finance initiative, known as the “Hustler Fund”. There is political controversy over where any savings should come from.

‘Justified public frustration’

Kell says that “there is justified public frustration in Kenya” that the Ruto government’s drive to increase tax revenue has not been matched by a reduction in spending on cabinet positions and salaries. Reducing government profligacy and corruption is one step [to overcoming debt issues], together with ensuring that infrastructure projects are motivated by long-term cost-benefit analysis rather than political expediencies.”

Furthermore, Osoro thinks that “there are clear contradictions” in the government’s economic strategy and approach to lowering the debt burden.

“Kenya has told the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that it is committed to fiscal consolidation – but to my mind that needs to be characterised by rationalisation and lower expenditure,” he notes. “While there have been attempts to increase the efficiency of tax collection, Kenya cannot push itself into a sustainable economic situation through tax measures alone.”

“A better policy route for me would be for Kenya to grow itself out of debt, rather than trying to tax itself out of debt,” Osoro says.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google