Despite its current predicament – hobbled by looting and political gangsterism – South Africa remains an economic giant in Africa, with nearly a fifth of the continent’s GDP.

So which way it points geopolitically in an increasingly turbulent and polarised world is significant for other African countries.

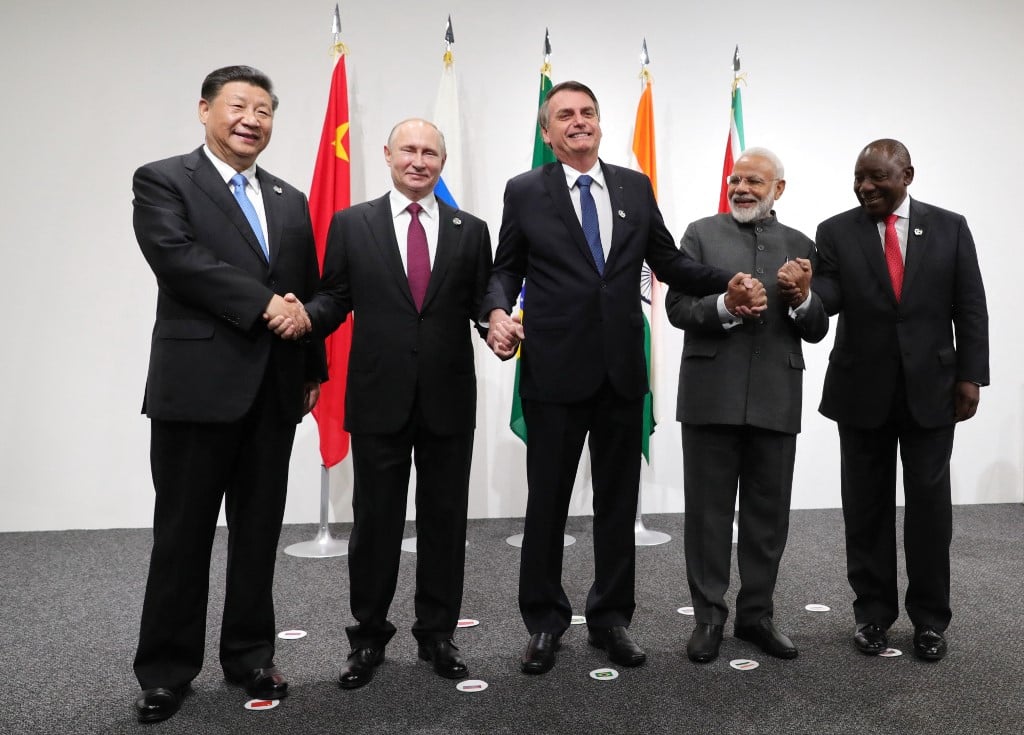

Is it toward the other BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China – or towards its long-established ties with the West?

Until now Pretoria seems to want to face both ways. But is this tenable any longer, especially with American President Joe Biden framing the choice as being between “democracy and autocracy”?

Between President Putin’s Russia and President Xi’s China on the one hand and, on the other, governments with the rule of law respected in functioning constitutional democracies.

A neat framing of the choice for Biden.

Who would want to side with Putin’s repression of human rights and poisoning of opposition leaders – or invasions of Georgia and Ukraine?

Or with Xi’s oppression of Uyghur Muslims, ruthless suppression of human rights, and bellicose threats to Taiwan?

But many African leaders remember that US post-World War Two imperialism invaded Vietnam, propped up dictators in Latin America and helped sustain apartheid.

Then there was the 2003 invasion of Iraq, launched on false intelligence that its brutal dictator had weapons of mass destruction, and which provoked regional bedlam.

By by-passing the United Nations, the US and the UK encouraged other countries to ignore international law and invade when they chose.

The Iraq war destroyed trust in the West. And left many Africa leaders reluctant to jump to America’s attention over Ukraine.

A “double standards” scepticism reinforced because Israel has remained protected whatever horror it unleashes on the Palestinians.

Also, although the old European colonial ties and subsequent investments still count a lot in Africa, new money and new influence from Beijing and Moscow counts too.

Beijing has been buying up Africa big time, especially its resources, somehow avoiding being charged with economic colonialism.

Moscow doesn’t have anything like the same money or share of trade, but Putin has used his mercenary force the Wagner Group, especially in the Sahel, Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Madagascar.

The deal Wagner offers is security in return for lucrative mining concessions, especially gold because with diamonds it can be used to evade sanctions by selling and exchanging them outside the regulated banking sector.

Elsewhere in the world, things are on the move too, as the old alliances come under pressure.

Putin’s war against Ukraine has triggered a weakening of Russia’s defences: the accession of Sweden and Finland to NATO doubles NATO’s presence along Russia’s border and increases its military defences over the trade routes and internet cables of the north Atlantic and Arctic.

The United Arab Emirates, once a steadfast US and UK ally, has been diversifying its strategic partnerships, continuing to host US troops and US Navy ships, whilst aligning with Russia in Africa. Dubai has also become a big hub for Russian sanctions-busting with over 4,000 of its companies based there.

In Africa the UAE has increased investments on the Continent, especially in ports, and works with Wagner Group mercenaries to combat and eliminate Islamic extremism and jihadism.

The UAE President has also established himself as a power broker in the Middle East region, aiming to undermine Islamic fundamentalism for example through forays into Libya, Sudan, Ethiopia and Yemen.

For its part another once-steadfast US ally Saudi Arabia has defied Washington by cutting oil production and edging closer to China on security cooperation. NATO member Turkey has shown similar waywardness in US eyes over closer Russian relations.

South Africa claims its fence-sitting over Russian atrocities in Ukraine is because it is “non-aligned”.

Hypocritical surely when many countries were rightly criticised for being “non-aligned” by sitting on the fence over apartheid?

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s cosying up to Putin also risks South Africa being expelled from the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa), a US law that gives duty- and quota-free access to the US market for selected African countries.

Although the Soviet Union may have been an important sponsor of the anti-apartheid struggle, today’s Russia offers South Africa little economically. Russian trade with South Africa is tiny (under one per cent) compared to Europe and the United States (over thirty per cent).

All this makes for a much messier multipolar world. The US may still be the dominant power, but geopolitics is shifting towards China and India, both set to supersede the US economically.

Interestingly, the UK’s former head of National Security Lord Sedwill wrote in The Economist in February: “Much of the world is rediscovering the appeal of non-alignment. So the West should reinvest in its relationships with countries such as Brazil, India, South Africa, Turkey and the Gulf states. Although many countries fear aggressive neighbours and few support Mr Putin’s invasion, they also complain of Western arrogance and double standards. Old friends we have neglected welcome China’s investment and its boundless appetite for the raw materials on which the modern economy and green transition depend. More private Western investment in the ‘global south’ could be unleashed if underwritten by political investment in sustained and stable relationships.”

Sound advice, especially since Africa is the only youthful continent – populations in the rest of the world have been ageing rapidly.

But there’s also the possible return of Donald Trump to destabilise the global applecart again. Trump Republicans have cavilled over US support for Ukraine and Trump would doubtless press a land for peace deal unacceptable to Ukraine which is in a life-and-death fight for national self-determination: it fears any deal would be a tactical pause for Putin to regroup, rearm and ready for a fresh attack to colonise the whole of Ukraine.

Surely the answer for Africa is not to be forced to choose between former colonial masters in the West, and new would-be colonial masters like Russia and China?

Surely there is an opportunity for African countries to promote self-determination with good governance, democracy, and human rights – and invite new trade with the BRICS as well as deepen older and much deeper economic ties with the West?

Not so much facing both ways as facing its own way?

For more insights on geopolitical issues and how they affect Africa, visit the IC Intelligence website.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google