Across three days in late May, the 2022 Ibrahim Governance Forum brought together world leaders, climate experts and African youth to discuss the nuances of the climate crisis in Africa and began to articulate the continent’s unique position ahead of Cop27 in Egypt.

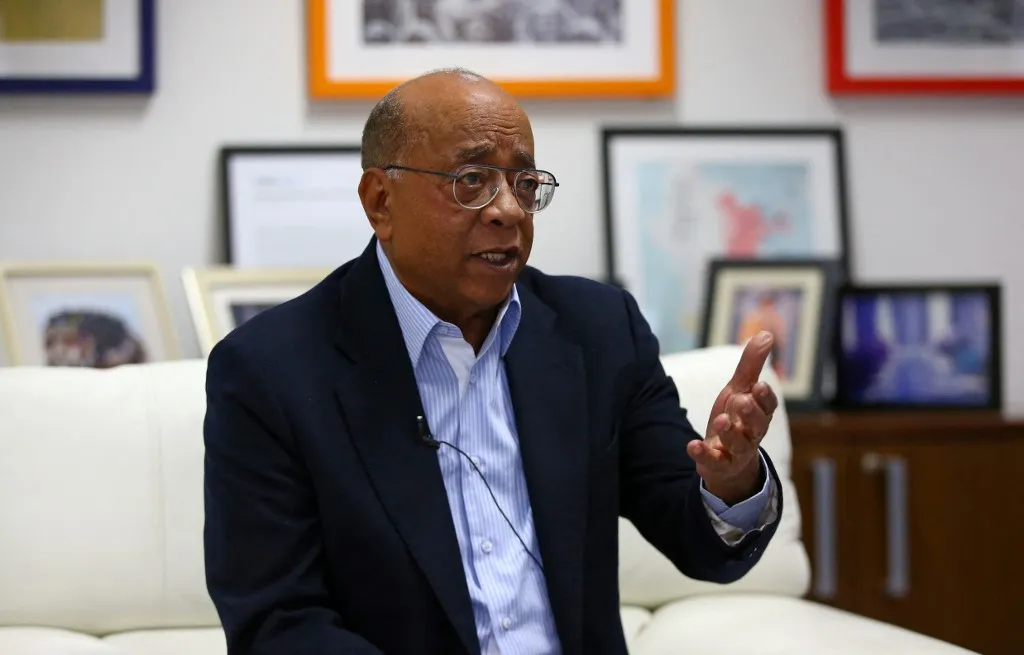

In the following interview, Forum founder Mo Ibrahim, the Sudanese-British telecoms billionaire, tells us why he believes Africa needs to be allowed to use its gas resources as a transition fuel to close the energy supply gap.

What is ‘Africa’s case’ at Cop27?

As Cop27 will be hosted by Egypt in November, it is a key opportunity to ensure that Africa’s specificity is correctly taken into account within the global debate and thus in the definition of relevant policies. Something that they have failed to do up until now.

“Africa’s case” can be articulated around three main points.

First, as the least industrialised continent, Africa is the continent least responsible for climate change. However, as, like Covid, the climate crisis knows no borders, this also means that Africa is the most vulnerable to its impact, with less adaptation means.

If this concerning vulnerability is not properly addressed, it will trigger more poverty and more instability, threatening thus the global commitments to reach the SDGs and ensure global security.

Second, we need to strike the right balance between climate protection and access to energy for all people on the planet, between climate justice and energy justice.

In Africa, 600m people still lack any access to electricity – twice as much as the entire population of the US. If we stick to commitments made at Cop26 to end fossil fuels financing, this means kicking away the development ladder for millions of Africans.

Last but not least, Africa’s potential in biodiversity, renewable energy sources, and minerals key to low-carbon economy, is to be seriously considered. The continent can play a pivotal role in a green sustainable economy, provided the relevant hurdles are correctly addressed: financial and human capacities, infrastructures, governance.

Cop27 is therefore an opportunity for Africa to put these considerations forward to the global community, and to ensure that the climate debate is inclusive of the continent’s specific needs and potential.

What is the role of gas as a ‘transition fuel’, and when should the transition end?

When we talk about the energy transition in Africa, the first thing to note is that the continent currently has the largest energy gap in the world: 600m people still live on a daily basis without electricity, and this is bound to grow, given demographic trends.

So, the one-size-fits-all approach adopted in Glasgow at Cop26 to phase out public and international fossil fuel financing totally overlooked Africa’s energy poverty, small carbon footprint and Africa’s people right to development.

In Glasgow the obvious aim was to move as quickly as possible to a complete reliance on renewable energy. I am not sure everyone is aware that in fact renewables already form an important part of Africa’s energy mix, with 22 countries – almost half the continent – already utilising renewables as their main electricity source.

I am not sure this can be matched by any other region in the world. However, there is no way renewables alone can in the short term meet the continent’s current and growing demand and ensure access to energy to the 600m people who still lack it.

So, it does not make sense, to say the least, to prevent Africa’s gas reserves from being used to help bridge this gap, which is a key development challenge. Eighteen African countries already produce gas, and gas is, by far, the least polluting of all fossil fuels (half as much as coal).

Tapping into this potential, with the adequate infrastructure and distribution channels, could help address energy poverty on the continent, while the environmental drawbacks of gas flaring and venting could certainly be addressed via relevant financing.

Natural gas must be considered as a transition fuel, to complement the key development in parallel of renewables, which must certainly be boosted, but alone are not yet in a position to meet the urgent energy needs in Africa.

Obviously, this transition period should end as soon as possible, but not to the expense of SDG7, for there is no hope of forwarding Africa’s development agenda without addressing the continent’s energy gap.

What are the trade-offs between climate and development?

Protecting our planet against climate crisis and ensuring development for all our people are both key. There can be no trade-off between them.

Climate change impact is undoubtedly putting the achievement of both the SDGs and Agenda 2063 at risk, which underlines the importance of adopting relevant measures for climate adaptation.

But we must also ensure that climate change mitigation solutions themselves do not have a damaging impact on development goals. Here again, access to energy for all people is a basic right that cannot be denied.

Indeed, Africa is actually ahead of much of the rest of the world on SDG13 on climate action, with almost three quarters of countries on the continent having achieved it. But when we look at SDG1 on poverty, SDG2 on hunger, and SDG7 on energy, Africa is severely lagging.

So, we need to balance carefully all this, and stop working in silos. Development on one side, climate on another, security on its side.

Are there any development pathways open to Africa that do not require fossil fuels?

As I said, Africa’s development agenda cannot move forward without addressing the continent’s energy gap and at present, there is no other viable alternative to using gas, the least polluting of all fossil fuels, as a transition fuel to close this gap.

What is the contribution of extended global supply chains to carbon emissions, and will AfCFTA assist in reducing these emissions?

Of course, global supply chains contribute to carbon emissions through transportation of raw commodities one-way, and processed products back the other – sea freight being by far the worst, as a recent report published by the AFC (Africa Finance Corporation) highlighted.

In Africa, boosting local processing of raw commodities and local manufacturing for growing local markets can definitely contribute to lowering carbon emissions at global level. This means a better integrated continent, where intra-African trade is consequently upgraded.

Obviously, the implementation of the AfCFTA is a key factor to help mitigate against these adverse impacts, through encouraging knowledge exchanges.

Will Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala’s position at the WTO help Africa improve its trading position vis-a-vis the rest of the world?

With her experience at the World Bank as within the Government of Nigeria, our sister is undoubtedly the best placed to deliver results not just for the most powerful economies, but also for the world’s poorest countries and the people who have been left behind.

I am confident that she can forward the African position by developing an inclusive global trade agenda that can lift millions out of poverty and bring shared prosperity to the world.

Are the links between trade and climate on her agenda?

Yes, and she’s made that explicitly clear in since taking on the role. She constantly and consistently highlights the key role that trade can play in cutting greenhouse gas by shifting the global economy to a low-carbon footing.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google