In 1986, as the apartheid regime in South Africa resisted international pressure, an ambitious Democratic senator from Delaware launched into a passionate rebuke of US government policy towards the pariah state.

Challenging secretary of state George Schultz on the ambiguity of Reagan administration policy, the energetic senator offered vocal support to the embattled black population of South Africa in a committee hearing.

“Dammit, we have favourites in South Africa. The favourites in South Africa are the people that are being repressed by an ugly white regime. We have favourites! Our loyalty is not to South Africa, it’s to South Africans. And the South Africans are majority black. They are being excoriated!”

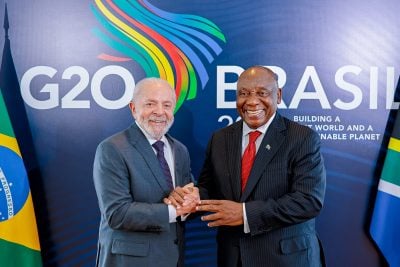

Thirty-four years later, nearly two weeks after his victory over incumbent President Donald Trump, that senator – now President-elect Joe Biden – spoke to South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, his first call with an African head of state following the election win. The leaders recalled Biden’s earlier visit to South Africa during the “dark days of apartheid”, and spoke of Biden’s recognition of Africa as “a major player in international affairs and in the advancement of multilateralism”.

Such a rapport would have been unthinkable during the administration of Donald Trump, whose attention in the 1980s was not directed towards apartheid but to real estate, the gossip columns of New York tabloids and Manhattan’s Studio 54 nightclub.

Throughout his one-term presidency, Trump’s engagement with Africa appeared scarcely more developed, as relations with the continent flitted between perfunctory and hostile. From launching an attempted travel ban on citizens from Muslim-majority countries including Libya, Somalia and Sudan to reportedly dismissing some African nations as “sh*thole countries” in an unrecorded Oval Office meeting, Trump did little to play down his “America First” stereotype.

Disengagement went beyond tactless comments. While Trump saw Africa as an arena for US competition with China, key diplomatic posts in Africa went unfilled and he failed to visit the continent. As the transition to Biden begins, US foreign policy experts hope that an outward-looking presidency will re-engage with Africa by resetting trade policy, boosting investment and cooperating on security and climate change. But after four years of drift, it will take more than a change of tone to re-establish the US as a major partner.

Even Trump’s critics concede that [he] shaped the outlines of an African commercial strategy that Biden can build on.

“I think US diplomatic relations with African states have not been given the level of seriousness or mutual respect they deserved under the Trump administration,” says Grant Harris, CEO of Harris Africa Partners and a former special assistant to the president and senior director for African affairs in Barack Obama’s White House.

“Under Trump the US didn’t even have an ambassador in South Africa for two and a half years, a lot of ambassadorships were slow to appoint, embassies were understaffed, and Trump said racist things about the continent. Trade and investment ties with Africa received little to no high-level attention, the president was not engaged and didn’t travel. There weren’t champions in the cabinet who understood the importance of increasing trade in and within African markets. Biden brings literally decades of experience on foreign policy issues. For decades he’s understood the importance of strong relations with African states.”

Yet even Trump’s critics concede that behind the crass exterior and shocking faux pas, the outgoing president’s transactional instincts shaped the outlines of an African commercial strategy that Biden can build on.

“With the Trump Africa policy, the tone was wrong, it was derisive, dismissive, disrespectful. Obviously that was a problem and we lacked senior level engagement,” says Aubrey Hruby, a Washington DC-based Africa investment advisor. “However, there were interesting positive aspects of the last four years that I hope are continued into the next administration. One was a focus on the commercial aspects of US-Africa policy.”

Building blocks of success?

On October 5 2018, President Trump signed into law the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act (BUILD), which established the United States International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), a new development bank that will invest in sectors across the emerging world including energy, healthcare, infrastructure, and technology.

The act gave DFC a lending capacity of $60bn, double that of its forerunner, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation – an organisation that President Trump considered scrapping before being convinced by allies that US overseas finance could combat the influence of a rising China. The unlikely product of the Trump era could become a game-changer driving US investment in Africa.

“The high point, the single most positive legacy of the Trump administration in my mind, will be the creation of the DFC. That is really important, that has a lot of potential,” says former Obama advisor Harris. “It gives more resources and flexibility to the US government to support companies. It’s a work in progress, the statutory authority is there, the resources are increased. The DFC currently has about $8bn worth of exposure to Africa, which is over half its exposure currently.”

While it’s too early to judge the DFC’s influence, its creation – and that of Trump’s Prosper Africa initiative, which combines the resources of over 15 government agencies to connect US and African businesses – offers a timely boost to US development finance capabilities as Africa emerges from the economic ruin of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“While it was stuttering in its rollout, the aim of facilitating and doubling US trade and investment matches African countries’ need to attract new investment, especially in a post-Covid world. These things are real structural tools that are available and are going to become more important in a post-Covid economic recovery, so this commercial aspect is a positive and should be continued,” says Hruby.

Zem Negatu, Ethiopian-American chairman of the Fairfax Africa Fund, says that while the DFC’s increased resources are an encouraging first step, persuading American investors to pursue African opportunities requires far more financial backing.

“In America we have the largest economy in the world. We can afford more than the $60bn that goes to DFC. China has the Belt and Road in the trillions. If we look at US private sector engagement in Africa, are we expecting it to bring about significant change or engagement? I doubt it. That needs public-private partnerships like Prosper Africa ramped up, and a hugely ramped up funding of DFC. $60bn is a start but it’s nowhere near what’s needed.”

Working with a rising China

While the fear of a rising China partly motivated Trump’s establishment of the DFC and may drive its future funding, a preoccupation with China’s influence in Africa has otherwise stymied US attempts to increase its influence on the continent. In a 2018 speech articulating the Trump administration’s Africa policy, then-US national security advisor John Bolton argued that China was dominating the continent by using “bribes, opaque agreements, and the strategic use of debt to hold states in Africa captive to Beijing’s wishes and demands”.

That view became central to the US conception of a malign Chinese role in Africa, with secretary of state Mike Pompeo prophesying dark consequences for Africa during his visits to the continent. Yet with US investment trailing China, there is no evidence that the strategy has led to a fundamental change in Africa’s friendly relations with China.

“The problem was not that the Trump administration was seeing rising China as a strategic imperative – that’s true and the Biden administration is seeing that as well,” says Hruby. “The issue is that they treated it as excessively zero sum – if a Chinese contractor got a project [in Africa] then somehow an American company lost, which is not the right way to think about it. If a Chinese company builds a road or railway it carries Pfizer products, Coca-Cola – that infrastructure gap is one of the problems with thinking about Africa from a market perspective.”

The US should be much more imaginative in its approach to China-Africa relations, to the extent that the new DFC should consider collaborating with Chinese companies on projects of mutual interest in Africa, says Zem Negatu. Where US and Chinese companies do not compete directly in certain sectors, there should be few blocks to successful collaboration. For example, Chinese construction companies could build Africa’s airports of the future while US plane manufacturers will provide the aircraft, he argues.

“It could even be a partnership with Chinese infrastructure or manufacturing companies; the financing could come partly from China. We could create a three-way partnership, US private companies, the US government and China. It seems a bit far-fetched today, but we need to be innovative. What’s the alternative? The way we were structured and the way we were going the Chinese would win hands down, so the US needs to rethink its strategy. It’s enlightened self-interest.”

Clarifying the terms of trade

Increasing investment on the continent – with or without China’s help – will rely on a predictable trade architecture, but as Biden’s transition teams fan through government, the legacy of a Trump administration fundamentally opposed to multilateral trade deals is becoming apparent.

From the untimely US exit from the Trans-Pacific Partnership to Trump’s backing of Brexit, the outgoing president’s contempt for multilateral trade was apparent. In Africa, that led to a preference for bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) – in July, the administration formally opened talks with Kenya, with whom it enjoyed two-way goods trade of $1.1bn in 2019.

“The Biden administration is going to walk in the door with huge amounts of trade disputes with allies and non-allies alike and having to make decisions about how it engages with the World Trade Organisation, and all of these things will need to be figured out by this team being set up right now,” says Harris.

The move towards bilateral FTAs in Africa has been criticised by trade experts, including Harry Broadman, chair of the emerging markets practice at the Berkeley Research Group, a former chief of staff of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers under George Bush, and a former international trade negotiator, who believes the US should shift back on to a multilateral track by supporting the newly established African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

“When you pick off bilateral FTAs with countries as important as Kenya, you start to deflate the balloon for the AfCFTA, and I think that is the single most important economic policy investment objective that the US should see for Africa. I’d suggest we pivot and put our energy into helping Africa launch the AfCFTA – without it we’ll be left with a large continent of small landlocked economies without economies of scale, which chokes off investment.”

Edward Alden, Bernard L. Schwartz senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, believes the US may follow through with the Kenyan negotiations.

“I think the Biden administration will probably try to finish off the negotiations with Kenya that are currently underway. I think it’s going to be awkward to stop those, so that may be one exception to their no new trade agreements – you could argue that that’s a continued trade agreement. I don’t expect to see significant new trade initiatives in Africa for a while though, I think like everything else on the trade agenda the Biden administration is going to move pretty slowly.”

The US will also have a crucial decision to make over the next director-general of the World Trade Organisation, the body at the heart of the global trading system. In October, the US blocked Nigeria’s Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, despite the assessment of a troika of WTO facilitators that she was the candidate best placed to gain a consensus among member states. Instead, the Trump administration continued to throw its support behind South Korean trade minister, Yoo Myung-Hee, arguing that a WTO in need of reform “must be led by someone with real, hands-on experience in the field.”

Biden will have to decide whether that resistance is sustainable, or consider whether unblocking the accession of Okonjo-Iweala, a former Nigerian finance minister, as the first African director-general of the WTO would be an easy diplomatic win as he resets relations with Africa.

“I do think the Biden administration will reverse course on the director general fight, the US is isolated on that and by blocking her candidacy the US is just making more enemies in Geneva,” says Alden.

Also in the bulging in-tray is a looming decision over the future of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a scheme that provides tariff-free access to the US market for African manufacturers but is currently due to expire after its latest extension in 2025.

“Even in the mid-Obama term, a lot of people in Congress were thinking about what happens beyond AGOA. It’s lasted 20 years, it’s simple and straightforward and gives open market access. But we haven’t seen countries able to take advantage because they don’t have the investment response. So renewing AGOA with a major effort on the commercial investment side is really important,” says Hruby.

Still, any major investment effort will have to be at least partly driven by the US private sector and the priorities of its CEOs, who have mostly betrayed an “ignorance” of African commercial opportunities, says Broadman.

“As a former trade negotiator your agenda is driven by what your stakeholders have at the top of their agenda. It’s got to be an interaction with the business community, consumer groups, and labour. The operative questions is how much of a clamour will there be on the part of US businesses and traders to raise the US game in economic relations with Africa? Unfortunately I don’t think, at least in the short run, that is at the top of the agenda. The challenge is on US government officials to articulate in a compelling way why trade and investment with Africa is important for US interests from a commercial and foreign policy objective. It’s got to be a two-way conversation.”

Refreshing the diplomatic corps

While resetting the priorities of a corporate America fixated on a Covid-wracked home economy might be a bridge too far for Biden, at least in the early months, he shows every intention of appointing a foreign policy team who can overcome his predecessor’s sidelining of traditional diplomatic expertise.

In November, it was confirmed that Biden had chosen Antony Blinken as his secretary of state. A former deputy secretary of state and deputy national security advisor with a traditional view of US alliances, Blinken will be radical break from his abrasive predecessor Mike Pompeo, a Trump loyalist.

“My understanding of the work he’s done is he’s a multilateralist and believes in the power of coalitions as a means of going forward with foreign policy… from what I gather he has both the discipline and demeanour to be an effective secretary of state,” says Broadman.

Biden also gained plaudits with his choice of Linda Thomas-Greenfield, who served as assistant secretary of state for African affairs from 2013-17, as the next US ambassador to the United Nations.

“Given her strong record on African affairs @StateDept, she is superbly-placed to rectify a sense of drift in US engagement on #Africa @UN since Nikki Haley arrived in 2017,” tweeted Richard Gowan, UN director at Crisis Group. While a slate of new diplomatic appointees will not by itself open a new era of economic relations with Africa or begin to address its yawning commercial deficit on the continent compared with China, the appointments may begin to persuade African leaders that the US under Joe Biden is under new management, shaking off “America First”, and ready to resume its interest in the continent’s affairs.

“A reimagined engagement with Africa is coming that will be completely different from the four years of the Trump administration,” says Zem Negatu.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google