This article was produced with the support of Backbase

The digital banking transformation is no longer an attractive option for African banks; it is imperative, if they are going to survive. Too many non-banking sector players have entered the market, making full use of the technology on offer, for them to keep doing business as usual. Most have recognised the revolution that is underway and are adapting the way that customers access their services, while others are automating their back office operations. Such changes should not only cut costs but will allow more people to access banking services for the benefit of all.

Despite various campaigns by governments, international organisations and the banks themselves, the customer profiles of many African banks have long been dominated by richer clients and larger companies, with the bulk of the populations, SMEs and informal workers excluded. This is partly because banks have not traditionally considered it commercially viable to provide services to those with limited financial resources, and often impose minimum balances that exclude the majority.

At the same time, it can be difficult for many people to access bank services in physical branches because branch networks are just not comprehensive enough, particularly in rural areas. The number of branches in Africa has not increased over the past five years and has actually fallen in South Africa. There are just five branches per 100,000 people on the continent, which is the lowest rate of any region in the world.

Online and particularly mobile banking is the obvious solution to this problem. Digital platforms are cheaper to provide than physical branches because the hardware and software required is cheaper at scale than building, maintaining and staffing branches. At the same time, they literally put bank services into the palms of customers. The growing sophistication of mobile phones, including lower prices for the smartphones and feature phones held by Africans, means that more and more financial services can be provided.

It is difficult to find comprehensive figures on the number of active digital banking users in Africa but figures from mobile trade body GSMA reveal that 469m people had used mobile money services on the continent by the end of 2019, including 181m active users. That represented a 12% increase in users during the course of 2019, while the value of transactions increased even more, by 28%, to $456bn spread over 23.8bn transactions.

Mobile money involves paying bills or people via mobile phone. It can be assumed that many of these users would be prepared to graduate to more advanced digital banking services. There were 102m active mobile money users in East Africa, in comparison with just 3m in Southern Africa, which has a more comprehensive banking sector, suggesting that mobile money fills the gaps left by the banks. As digital banking takes off, it will be interesting to see how it fairs in comparison with mobile money.

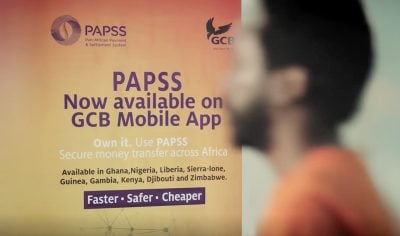

International consultants McKinsey forecast that the number of Africans with bank accounts will increase from nearly 300m in 2017 to 450m by 2022, with revenues rising from $86m to $129m over the same period. This is likely to be driven by the rapid adoption of digital services. Most African banks now offer internet banking services and mobile banking apps to their customers to allow balances to be checked, money transferred and bills paid. Digital lending and mobile wallets are also becoming more popular.

Bank structures

All sectors of the economy are interconnected but none more so than banking. Access to banking services underpins the success of every other industry, so it is vital that the bulk of the African population is included as soon as possible. As our Survey Analysis on pages 7-9 of the Digital Banking report demonstrates, African banks are increasingly buying into the transformative nature of digital platforms and are putting them at the heart of their corporate development, rather than just adopting them as one element among many.

Although it seems clear that most bank customers have still not used digital services, banks are investing in the architecture needed to host more services in order to reduce their own operating costs but also to ensure that they do not miss out on a new generation of generally urban, middle class customers who expect to carry out more of their interactions online. Failure to do so could mean losing customers to non-mainstream fintech companies and new digital-first banks, as well as their traditional competitors. However, embracing the technology could see more cooperation with fintech and challenger banks rather than merely seeing them as the enemy.

Digitisation can also help banks in terms of back office functions by automating credit processes for individual and business customers. Research by McKinsey published in June 2020 found that just 9% of personal loan applications were processed digitally in Africa. It recommended the use of high performing credit engines and know-your-customer (KYC) processes. It also suggested partnering with fintech companies “to accelerate their own innovation in risk models and address talent gaps while enabling fintech players to achieve scale”.

Shrinking branch network

The number of physical bank branches used to be an indication of the penetration of banking services within any particular society but that link has been eroded and will be broken in the longer term. The process is being speeded up by the Covid-19 pandemic, which has encouraged more people to bank online or via mobile phone because of branch lockdown closures. Banks have also supported this trend in order to continue providing much needed banking services. Some, such as Uganda’s biggest commercial lender, Stanbic Bank, encouraged customers to switch to its digital banking platforms by suspending digital transaction charges.

Some customers who were previously unwilling to access digital banking services were left with no option because of lockdown branch closures and have now tried mobile and online banking for the first time. Platforms are generally very easy to use for anyone with experience of any type of online or mobile service and so it will be interesting to see how much of a long term increase in digital banking users is generated. Once customers have discovered how easy they are to use, they may not want to revert to visiting their local branch.

Some fear that the temporary closure of branches could encourage banks to close them permanently. There is obviously a balance to be struck between ensuring that customers are still able to access services and driving a wholesale switch to digital banking that will leave some customers behind. Yet there seems little doubt that the crisis will accelerate the transformation, not least in the minds of those bank executives who had previously been more firmly wedded to traditional bank strategies. It will be interesting to see how banks are able to integrate physical and digital banking provision, including by retaining some face-to-face contact when it is really needed.

Increased mobile ownership

The digital banking revolution is being underpinned by the mobile telecoms boom. Most Africans access the internet via mobile phone, so improved access to smartphones will only speed this process up. Mobile phone penetration rates have rocketed in Africa over the past few years. According to industry body GSMA, the number of SIM connections on the continent is set to increase from 747m at the end of 2017 to 1bn by 2025, although of course some people have more than one SIM, perhaps to separate work from personal life, so penetration rates are not quite as high as some claim.

Smartphone penetration rates are lower but still climbing: from 15% of the continent’s population in 2014 to about 35-40% at present, although this figure varies widely from country to country and functional phones still occupy a high market share. Total online penetration rates are increasing too but differ massively across the continent, from 4.7% in Western Sahara to 87.2% in Kenya.

The level of technology and services available on budget smartphones, including on many produced by Chinese companies, has increased sharply even over the past two years. A number of models now retail at less than $100. Innovations such as longer lasting batteries, AI power management and power saving modes are making them increasingly attractive in areas where access to electricity is still limited. There seems little doubt that prices will continue to fall in the near future, partly through the manufacture of models in Africa itself, including in Ethiopia, driving smartphone penetration rates still higher.

This article is part of the Digital Banking report by African Banker and Backbase. Visit the report homepage to access the full report.

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google