Entrepreneurs, business leaders, and investors are increasingly questioning whether the traditional traditional venture capital (VC) model – largely imported from the United States and Europe – is optimal in a specifically African context.

By 2019, VC funding in Africa had soared to over $2bn – with funding reaching a record high of $5.2bn in 2022, partly driven by the environment of ultra-low interest rates that freed up cheap capital for investment in both developed and emerging markets. The total raised last year amounted to around $3.6bn, but it remains the case that Africa has witnessed an extraordinary boom in this asset class in a short space of time.

Tarek Mouganie, founder and group CEO at Accra-based digital banking platform Affinity Africa, argues that the VC model has helped solve some fundamental issues in African markets but that it also needs to be better tailored to conditions on the continent.

Speaking to African Business from the Ibrahim Governance Weekend in Marrakech, Mouganie says VCs play a critical role in funding ventures that traditional investors, such as development finance institutions (DFIs), would deem too risky.

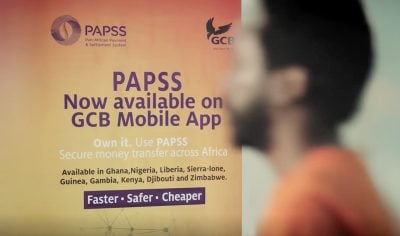

“I work in the space of financial inclusion. 60% of adults in Sub-Saharan Africa do not have bank accounts – that is over 400m adults. In Ghana, which is a developed, low-middle income country, there are still 11m adults without a bank account and transactions are still 90% cash based,” he explains. “This is not a problem – it is a huge opportunity to build something that solves this.”

“But to get a banking licence and prove this concept, you need deep pockets. In Ghana it costs between $3m and $60m depending on which type of licence you want – then you need additional funds to reach capital requirements,” Mouganie adds.

“A DFI such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which is funded by taxpayers, is not mandated to take this kind of risk. What was amazing about the VC space is they came into Africa to plug that gap, assume the risk, and build their portfolios. We’ve had great success stories in fintech as a result, solving huge issues in Sub-Saharan Africa.”

An entirely different context

However, Mouganie and others suggest that the majority of VC funds, which are largely based outside of the continent, do not always have a firm grasp on the nuances of local markets.

David van Dijk, co-founder of the African Business Angels Network (ABAN), says: “I keep being surprised there are still people who parachute in from the West and just assume their Silicon Valley model or concept or widget will just take the African continent by storm.”

Mouganie suggests that this type of attitude stems from a lack of awareness. “My question is this: do you think a VC based out of Palo Alto even knows what mobile money is? A lot of these people and the large VCs piled into Africa in 2021-2 and simply tried to replicate their existing VC model.”

Adesuwa Okunbo Rhodes, founding partner and CEO at Aruwa Capital Management in Lagos, noted at the Ibrahim Governance Weekend that VCs often approach African markets seeking to invest in Africa’s answer to global tech giants such as Amazon – without appreciating that Africa operates in an entirely different context and, most importantly, with much more limited infrastructure. “There is no Amazon without roads,” she says.

Mouganie adds: “if you are asking for someone to build an Amazon in Africa, you need roads, you need electricity, you need access to mobile data – and affordable mobile data, because it currently [can cost] four times more than in the European Union, and people do not earn four times the amount they do in the EU. You need warehousing, supply chains, distribution facilities, and postal services.”

“Amazon has created a layer for consumers, but the infrastructure behind it existed in the past. A large VC fund based in the US does not know all this stuff.”

Longer timeframes crucial

How could the VC space be better tailored to the African continent? Mouganie suggests that longer investment timeframes would be a strong start – if a VC operates on a three-to-five-year model in the US, they should implement at least a six-to-ten-year model in Africa to reflect the increased complexity that comes with building profitable businesses on the continent, he says.

Partnering more with local firms and individuals would also allow VCs to gain a better understanding of how African markets work in practice, he says, and mean they approach investing on the continent in a more realistic and productive way.

There have been some moves towards more collaborative approaches to investment in different asset classes. Dylan Malloy, managing director of the New York-based consultancy firm Bridging Ventures in New York, tells African Business that they are working to “line up different strategic investor partners to start building a new fund model”.

“We are designing and incubating a private equity fund that invests alongside public commitments for a just transition – we are building out a network of partners in Africa so we can lead through understanding what is happening on the ground and how we can play a role.”

Healthier attitude to risk required

Besides these structural changes, Mouganie also argues that a change in mindset is needed – particularly when it comes to risk. “In Silicon Valley, the typical model is “disrupt first, ask questions later.” You see all these AI companies in California raising billions of dollars to do this and it is ridiculous.”

“We cannot take these same risks because our ecosystem is more fragile. If anything were to happen to Affinity and we lost depositor funding, do you think our clients, who are moving from cash to banks for the first time, would ever return to banking?” Mouganie asks. “Our economies as well – they are not strong enough to absorb those kinds of shocks.”

While the VC space in Africa is still in an early stage, there are signs that it is starting to adapt more closely to local environments. Mouganie says that, since funding has scaled back after the post-pandemic period, “local VCs with local experience have stepped up and doubled down.”

“It has forced the existing VC players on the market to stand up and say – ‘we know what is going on in Africa.’ How do we rewrite this narrative and make sure we do not only provide what our donors and funders need, but what our founders need to enable an innovative environment?”

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google