Alan Doss’s career with the United Nations took him to some of Africa’s most complex conflict zones as a peacekeeper – Sierra Leone, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

In the first two parts of A Peacekeeper in Africa: Learning from UN Interventions in Other People’s Wars, he delves into the operations he experienced, while in the latter sections he reflects on the nature of peacekeeping and its future.

He starts by reminding us that very few modern conflicts in Africa have been wars of territorial conquest. The decision to abide by the colonial demarcation of national borders that created multiethnic, multicultural and multilingual states inevitably led to internal conflicts erupting throughout the post-colonial era.

“Instead of wars between countries, many smaller wars have erupted within countries as various groups and leaders struggle to capture or resist the state, spawning abusive regimes and rapacious rule, sometimes with the support or connivance of external powers,” he explains.

In such cases, the request of an existing government, “no matter how ineffectual, unrepresentative, or vile that government might be”, can be enough to mobilise a UN peacekeeping force.

A common misperception is that the peacekeepers are there to prop up these governments, but Doss makes clear that this is absolutely not the case.

“Robust peacekeeping is essentially tactical in nature – intended as a short and sharp intervention to deal with a specific, localised armed threat. In my experience, it worked best when the threat was confined to a limited geographical area and relatively accessible terrain.”

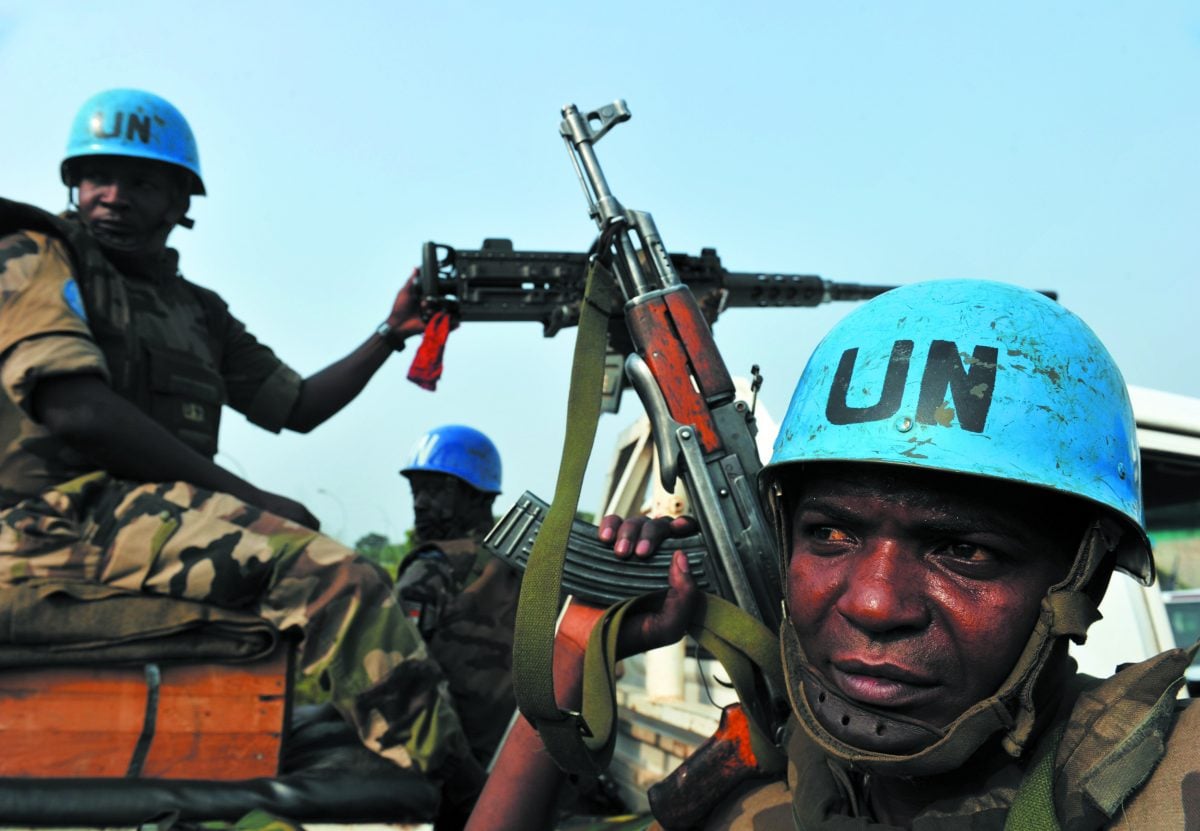

Doss views the use of UN peacekeeping as an absolutely crucial tool of humanitarianism, and begins his recollections with his time in Sierra Leone, where he was posted in 2000. He sketches its history, recalling its early years under British colonialism as a colony for freed slaves, before charting the decline and fall of the independent state, which culminated in civil war and the rise of the brutal Revolutionary United Front (RUF). This “dystopian amalgam of the dispossessed, the discontented, and the defenseless” triggered regional, international and UN military interventions.

“By the time I reached Sierra Leone,” Doss recalls, “the horror of the conflict – characterised by amputations and AK47-toting child soldiers – was widely known.”

Nearly half the 4.5m population had to flee their homes because of the war, but Doss was impressed at the way they were able to resume their lives as soon the RUF was pushed back.

Many factors contributed to the war’s end – political, diplomatic, military and personal – but he lists the capture and imprisonment of RUF leader Foday Sankoh as pivotal.

Côte d’Ivoire: ‘A conflict of layered complexity’

After three and a half years in Sierra Leone, Doss relocated to Côte d’Ivoire, where the terms of a ceasefire agreed in January 2003 between the government and rebel forces had led to a de facto partition of the country.

He neatly summarises the path that led to war. While the country largely avoided the serial coups of Sierra Leone, partly owing to a stable relationship between President Félix Houphouët-Boigny and former coloniser France, a fundamental challenge later arose from the migrant-dependent growth of the Ivorian economy. A post-independence economic “miracle” was founded on plantation agriculture manned by immigrant labour from Burkina Faso and Mali.

When Houphouët-Boigny died in 1993, his successor Henri Konan Bédié set about modifying the electoral roll to exclude candidates whose parents had not been born in Côte d’Ivoire or who had not lived in the country for five years, a requirement termed Ivoirité. The issue became a central element in the political crisis that enveloped and profoundly destabilised Côte d’Ivoire.

Rebels consolidated their hold in the northern half of the country and were joined by two armed groups from the west. As Abidjan descended into chaos, Doss feared that militias would turn their anger on the communities of West Africans and northerners in the city: “If that happened, and notwithstanding our protection-of-civilians mandate, we would have been hard-pressed to prevent massacres.”

Doss’s stay in Côte d’Ivoire was relatively short but discouraging. “Unlike my departure from Freetown, I left Abidjan with a sense of unfinished business,” he writes. “This was a conflict of layered complexity and not simply a repeat of the ‘good versus evil’ struggle that characterised the war in Sierra Leone.”

Liberia: Starvation and sexual violence

He was subsequently posted to Liberia, which had endured a quarter-century of brutality, social disorder, and economic collapse. The violence and its consequences, including starvation, killed at least 250,000 people, and displaced many more.

Liberia’s descent into chaos was marked by three phases. First was the ascension of Samuel Doe after a 1980 coup, ending with his gruesome murder a decade later. Doe’s death ignited a second phase of conflict marked by internecine warfare that eventually brought Charles Taylor to power in 1997. The third phase began in 1999 and ended in 2003 with Taylor’s exile to Nigeria and the establishment of the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) as a peacekeeping force.

Elections saw Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf become Liberia’s leader, and her progressive policies soon made the path to sustainable peace a viable reality.

But even as the conflict ended, lawlessness increased dramatically. Doss was confronted with evidence of the prevalence of rape, and UNMIL personnel were complicit.

Sexual exploitation remains a constant quandary for the UN and many NGOs, a scourge which Doss says has done great damage to the reputation of peacekeeping despite the lack of progress on a solution.

“In the gravest cases of sexual exploitation and abuse involving military personnel,” he writes, “our inability to go beyond a call for the offenders to be recalled and prosecuted – the UN has no prosecutorial authority over the troops or police deployed to peacekeeping operations – severely damaged mission credibility. It is very unlikely that this policy will change. The prospects of any government handing over prosecutorial power to the UN to sanction its own troops seem highly unlikely.”

Sexual violence by militias was a major problem when Doss arrived in the DRC as the UN secretary general’s special representative.

“Sexual violence in the Congo eclipsed even the horrors that had been inflicted on the women and girls of Sierra Leone and Liberia,” he writes.

Can the guns be silenced?

Doss draws on his experience in the four countries to reflect on the nature of the UN’s peacekeeping role.

“Does peacekeeping have a future?” he asks. “I would like to say no, safe in the belief that conflicts of the kind in which the UN has intervened in recent decades will be prevented in the first place.

“But I fear that this will not be the case. Given the international community’s mixed record on conflict prevention, I anticipate that UN peacekeepers will continue be called upon to intervene in other people’s wars.”

This is a fascinating book from a peacekeeper who has seen much but is still grasping for answers.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google