Health experts say next week’s Africa Climate Summit offers a high-stakes opportunity to prioritise a sector that is on the frontline of the human impacts of global warming.

In Southern Africa, countries such as Botswana, eSwatini, Namibia, and Zimbabwe have experienced a dramatic surge in malaria cases in 2025 after a drought followed by above-average rainfall led to optimum conditions for mosquito breeding.

These climate change impacts cause life-threatening harm to communities across Africa – particularly for women and children – while further burdening already stressed health systems.

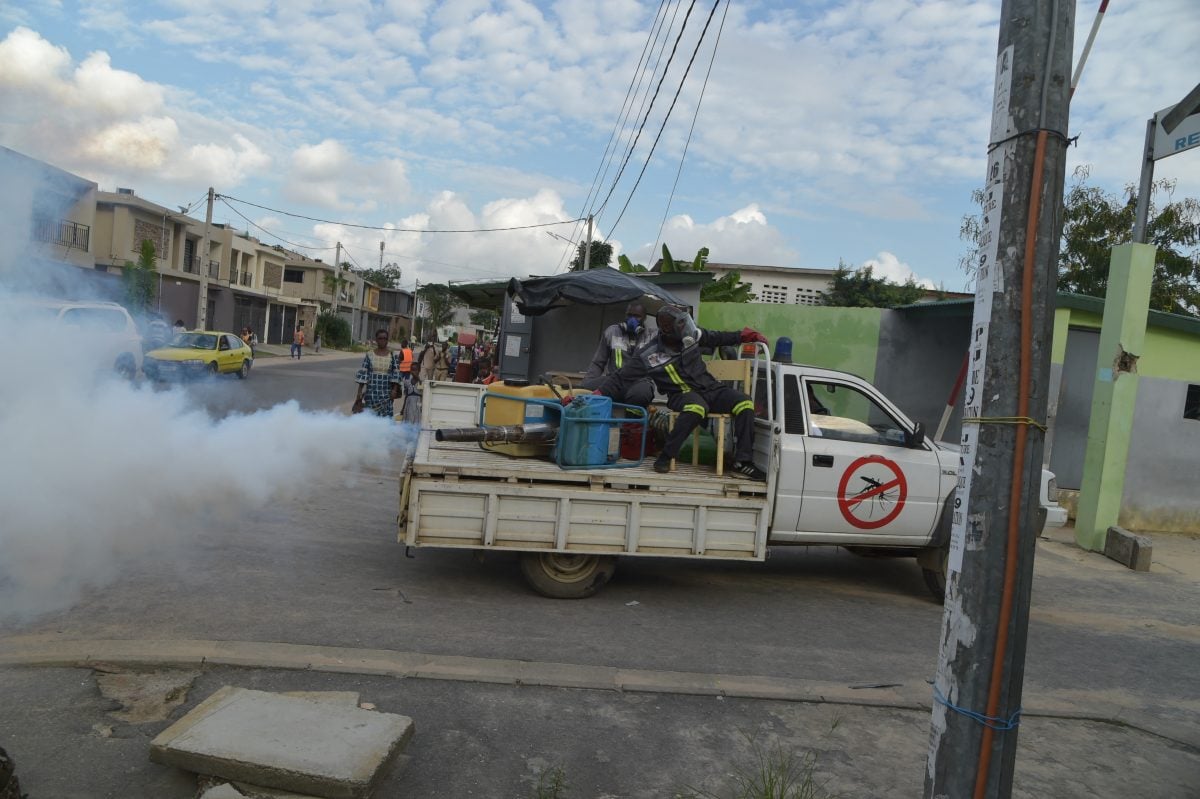

Mosquitos at large as weather changes

Aggrey Aluso, executive director at Resilience Action Network Africa (RANA), an advocacy organisation, said the continent is among the most vulnerable to climate impacts, including heatwaves, prolonged droughts, and heavy rainfall that create ideal conditions for disease outbreaks.

“Evidence shows a 63% increase in zoonotic outbreaks over the past decade, highlighting how environmental shifts are driving a silent but deadly health emergency,” he told African Business.

Africa is also witnessing the expansion of vectors such as Aedes mosquitoes, which cause yellow fever, due to warmer temperatures.

Tafadzwa Mabhaudhi, a professor of climate change, food systems and health in the Department of Population Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said temperature and rainfall changes affect mosquito breeding, biting frequency, and the development of parasites within vectors, leading to shifting and often extended transmission seasons.

“The science tells us that climate change is significantly impacting malaria and other vector-borne diseases in Africa by altering the geographical distribution, seasonality, and intensity of these diseases,” he said.

“Typically, during droughts, people dig a lot of wells and create water storage close to homes as a coping strategy. If, in the subsequent season, we receive heavy rains, all these spots will then create breeding sites for mosquitoes that are close to homes, which may lead to an increase in malaria cases.”

Though Africa is the world’s most populous continent after Asia, it is responsible for only about 4% of global emissions. But as temperatures rise and extreme weather events occur with greater frequency and intensity, the cost of climate change is growing on the African continent. Most poor African countries are the least able to pay for the damage. Africa warmed faster than the rest of the world, according to a report released by the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) in 2024. The World Health Organisation (WHO) considers climate change a fundamental threat to human health.

A study on vector‑borne infectious diseases in pregnancy in the era of climate change reveals that the situation is likely to worsen with time. The geographic range of malaria is expected to expand into higher elevations and temperate regions by mid-century, with transmission suitability increasing in East Africa and parts of South Asia.

The expansion is already happening in many high-burden malaria countries across Africa. Sungano Mharakurwa, a professor and director of Africa University’s Malaria Institute, said he has been observing disease epidemiological shifts that are associated with changing climate patterns.

“These include the encroachment of malaria in areas that were previously always non-malarial areas, such as so-called ‘highland malaria’, and concomitant expansion in vector habitat, as well as novel vectors actively transmitting the disease in such non-traditional malaria zones,” he told African Business.

Vector-borne diseases associated with rising temperatures and shifts in rainfall patterns, such as malaria, dengue or Zika and other viral or bacterial infections transmitted by mosquitoes, ticks, midges, and flies disproportionately affect pregnant women and children. Infections from these vectors can trigger miscarriage, or cause stillbirths, preterm births, low birth weights and congenital anomalies.

“Children under five years are a vulnerable group and have the highest burden of malaria deaths,” says Mabhaudhi. “Besides accounting for most malaria deaths, it can also cause anaemia and stunted growth in children, affecting their overall growth and development, with lasting impacts into their adult life,” he said.

In 2023, Africa accounted for 94% of the 263 million malaria cases recorded globally, according to the WHO. The continent also accounted for 95% of the 597,000 malaria deaths in 83 countries. Children under five accounted for about 76% of deaths in the region.

Summit offers opportunity

As African leaders, policymakers, private sector, climate and adaptation finance partners gather in Addis Ababa from 8 to 10 September for the second Africa Climate Summit, there is an opportunity to mobilise resources to fund effective mitigation and adaptation initiatives that can avoid unbreakable health risks brought by climate change across the continent.

In 2001, African Union governments adopted the Abuja Declaration, in which they set a target of allocating at least 15% of their national budgets to improve health care. But decades later, the majority of the African countries are spending far less of the targeted percentage.

Aluso said the summit is a critical opportunity for African leaders to mobilise and demand resources the health impacts of climate change.

“Strengthening climate-resilient health systems and centering health in climate action are therefore urgent priorities,” he says. “Integrating health into climate policies and adaptation financing frameworks is no longer optional – it is urgent.”

He said he wants to see dedicated adaptation financing for climate-resilient health systems – which is grant-based, predictable, and accessible – aligned with the Africa Centre for Disease Control’s Climate and Health Strategy, as well as the integration of health into countries’ nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and national adaptation plans (NAPs).

Mabhaudhi hopes that Africa Climate Week’s discussions around health and climate change could trigger long overdue political action.

“What is critical will be to turn this growing interest and political will into climate action on the ground, tangible adaptation financial commitments through increased budget allocations to climate and health, and greater coordination across science, policy, and practitioners to avoid fragmentation of efforts,” he said.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google