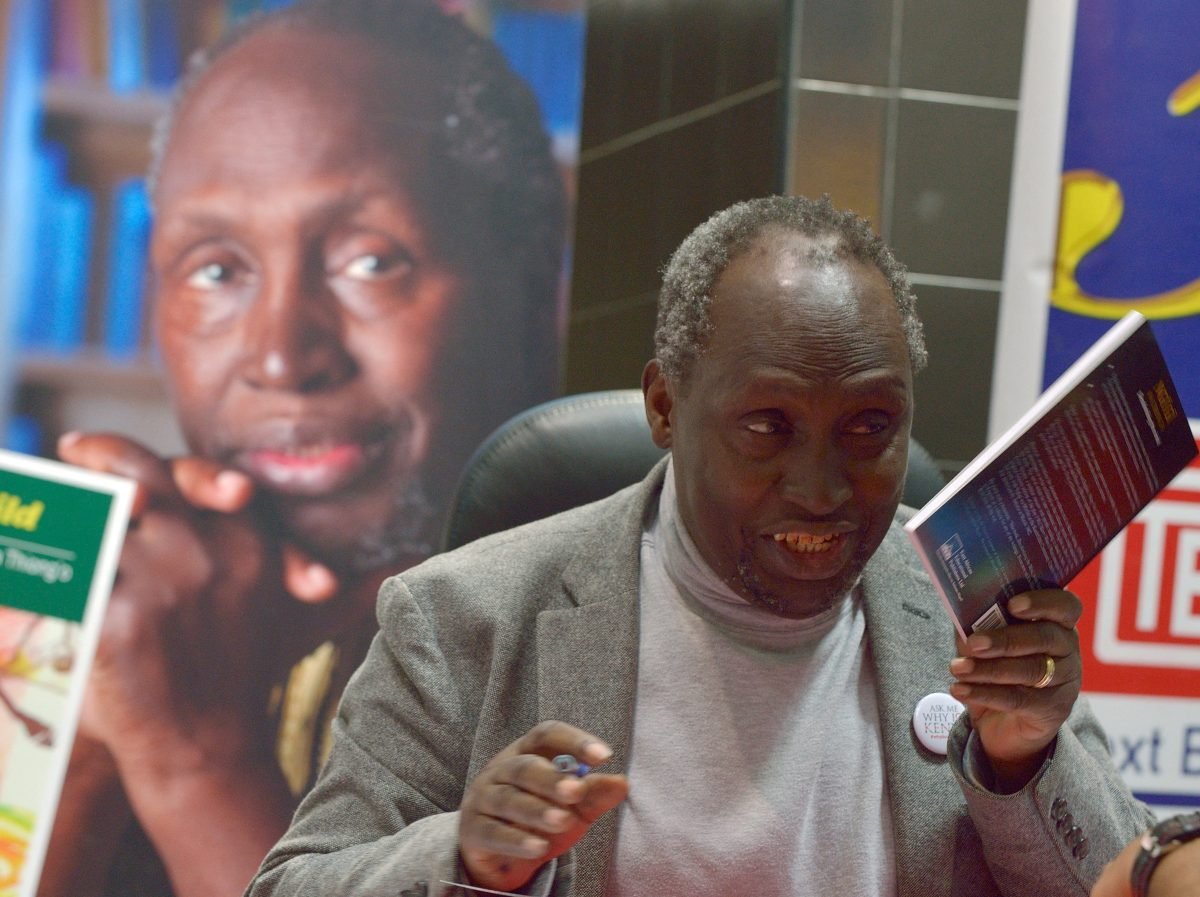

Few lives are lived so remarkably that, when someone passes, admirers and news outlets cannot agree on how to describe the person. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is one such man. Throughout his life, Thiong’o was not only a novelist, poet, and academic, but also a political prisoner, tireless advocate for native African languages, and, some argue, East Africa’s foremost novelist.

As Kenyan journal The Elephant poignantly stated after his death, “To call him merely a “great African writer” would be to shrink his genius – he was one of the most vital thinkers of our age, a voice who spoke from Kenya but to humanity.” Thiong’o’s death was announced by his daughter, Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ, and the news was met by an immediate outpouring of tributes from the likes of Kenya’s President William Ruto and Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, a testament to his impact and legacy not only across Africa, but around the world.

Thiong’o was born James Ngugi in colonial Kenya in 1938 in the rural village of Kamirithu to a farming family whose land had been repossessed under the British Imperial Land Act of 1915. His formative years were marred by tragedy as his family became involved in the 1952–1960 Mau Mau Uprising. His half-brother Mwangi was actively involved in the Kenya Land and Freedom Army resistance and died as a result; another of his brothers was deaf and was shot dead by soldiers whose orders he did not hear; and his mother was tortured at a home guard post in the family’s home village.

At the age of seventeen, Thiong’o left Kamirithu to attend Alliance High School near Nairobi, but returned during holidays to find his village razed by colonial forces. Despite these tragedies he faced at such a young age, his academic prowess led to him being accepted at Makerere University in Uganda, where he earned his BA in 1963, then to the University of Leeds in England in 1964.

A literary breakthrough

Thiong’o’s literary career began by writing in English. His debut novel, Weep Not, Child (1964), is credited as the first major English-language novel from East Africa and tells the harrowing story of Kenyan brothers confronting British colonial brutality during the Mau Mau rebellion. The manuscript gained exposure when Chinua Achebe secured its publication in the Heinemann African Writers series after reading it at the 1962 Makerere writers’ conference. The novel went on to win UNESCO’s first prize at the 1966 World Festival of Black Arts in Senegal.

His subsequent novels and plays, published throughout the 1960s, explored the complexities and the fallout of the colonial and post-independence era. Also written in English, The River Between (1965) explores divisions between Christians and non-Christians, and A Grain of Wheat (1967) is set during celebrations for Kenya’s independence day, regarded by some critics as his best work. His play The Black Hermit (1962), dramatises a conflict between tradition and modernity, and The Trial of Dedan Kimathi, written in 1976 with Micere Githae Mugo, focuses on a Mau Mau leader.

In 1967, Thiong’o was appointed professor of English literature and fellow of creative writing at the University of Nairobi. By this stage, he had grown increasingly critical of writing in English, viewing it as a lingering remnant of colonialism. He began to argue for the re-formation of the department to place African literature, including oral literature and writing in African languages, at its centre. At this time he changed his name from James Ngugi to Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, and published a series of influential essays, published together in Homecoming: Essays on African and Caribbean Literature, Culture, and Politics (1972). His final English novel, Petals of Blood (1972), offers a savage indictment of postcolonial corruption in Kenya – a theme that he would continue returning to in his future works.

In that same year, he co-founded the Kamirithu Community Education and Cultural Centre and created the grassroots Kikuyu-language theatre. Their debut production, Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), premiered in October 1977 to a crowd of 10,000. The plot exposed class injustices and exploitation, which led to its ban by the Kenyan government after just six weeks.

Not long afterwards, Ngũgĩ was arrested and detained without trial in Kamiti Prison, during which he penned his first novel in Kikuyu, Caitaani Mũtharaba-Inĩ (Devil on the Cross), on toilet paper. While he was in prison, the Kamiriithu Community Center began a production of Maitu Njugira (Mother Sing for Me). However, the government withdrew the centre’s licence for public performance in November 1977 and banned all theatre activities at the Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre in 1982. The day afterwards, the theatre was destroyed by armed police.

Advocate of African languages

During his time in prison, Ngũgĩ decided to stop writing his works in English and began writing in his native tongue, Gikuyu. In an interview later in life, he described himself as a literary migrant, stating “I had to be away from my mother tongue to discover my mother tongue.” His time in prison also inspired the play The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (1976) which explores the role of Kenyan women in the Mau Mau movement.

After his release in December 1978 he was stripped of his University of Nairobi post and fled into exile in 1982, first to the UK and then to the US. While in exile, he worked with the London-based Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners in Kenya and published Matigari ma Njiruungi (translated into English as Matigari).

He eventually settled in California and established the International Center for Writing and Translation at UC Irvine. His later works include Detained (1981), his prison diary published in English and Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986), an essay arguing for African writers’ right of speech and expression in their native tongues rather than European languages, with the aim of severing remaining colonial ties and building an authentic African literary canon. In the work, he urged the continent to reclaim “its economy, its politics, its culture, its languages”, emphasising orality and hitting out at a “neocolonial bourgeoisie.”

Despite continuing to live in the US, Ngũgĩ continued to write and publish in his native Gikuyu into the 21st century.

In 2004, he visited Kenya for the first time in decades– and he and his wife Njeeri were subjected to a violent robbery in which she was raped. He had already faced multiple health crises throughout his life; in 1995, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and given only months to live, but recovered.

In 2006, this novel Wizard of the Crow was published, translated to English from Gikuyu by Ngũgĩ himself.

His later published works include Globalectics: Theory and the Politics of Knowing (2012), and Something Torn and New: An African Renaissance, a collection of essays published in 2009 that make an argument for the crucial role of African languages in “the resurrection of African memory.” This was followed by two autobiographical works – Dreams in a Time of War: a Childhood Memoir (2010) and In the House of the Interpreter: A Memoir (2012), which was described as “brilliant and essential” by the Los Angeles Times.

In 2019, Ngũgĩ’s prose novel The Perfect Nine was published, celebrating mythic Kikuyu female ancestors. Translated into English in 2020, it became the first work in an indigenous African language longlisted for the International Booker Prize. This was just the latest in a long list of accolades stretching back decades. Throughout his life, Ngũgĩ earned widespread acclaim, including the International Nonino Prize (2001), the Park Kyong-ni Prize (2016) and the PEN/Nabokov Award (2022). On many occasions he was considered a contender for the Nobel Prize, though he was never awarded it.

A revolutionary career

While Ngũgĩ’s death may close a chapter in Kenyan literary history, his influence continues to resonate through his literary masterpieces that laid bare the open wounds of colonialism and the injustices of post-independence rule. His revolutionary decision to pivot from English to indigenous languages including Gikuyu and Swahili will endure.

Ngũgĩ’s outspoken criticism of both colonial systems and authoritarian regimes in Kenya made him a target, but also a figurehead. He was beaten, imprisoned, exiled, and robbed, yet never silenced, and his work will live on.After his death, his daughter proclaimed, “He lived a full life, fought a good fight.” She spoke not just of his longevity, but of his cultural, and moral impact cemented over almost nine decades. His work underscored the belief that language is identity, and that liberation starts with speech. The man himself may be gone, but his ideas and convictions will endure in every person who dares to write, speak, or even dream in their own mother tongue.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google