Currency difficulties are one of the biggest obstacles to intra-African trade. Big contracts are often conducted in US dollars or other non-African hard currencies but there is a lack of these across the continent. At the same time, confidence in many African currencies is weak because of fluctuating exchange rates, including against the dollar. A single African currency would make the continent more independent but there is a long way to go before this becomes a reality.

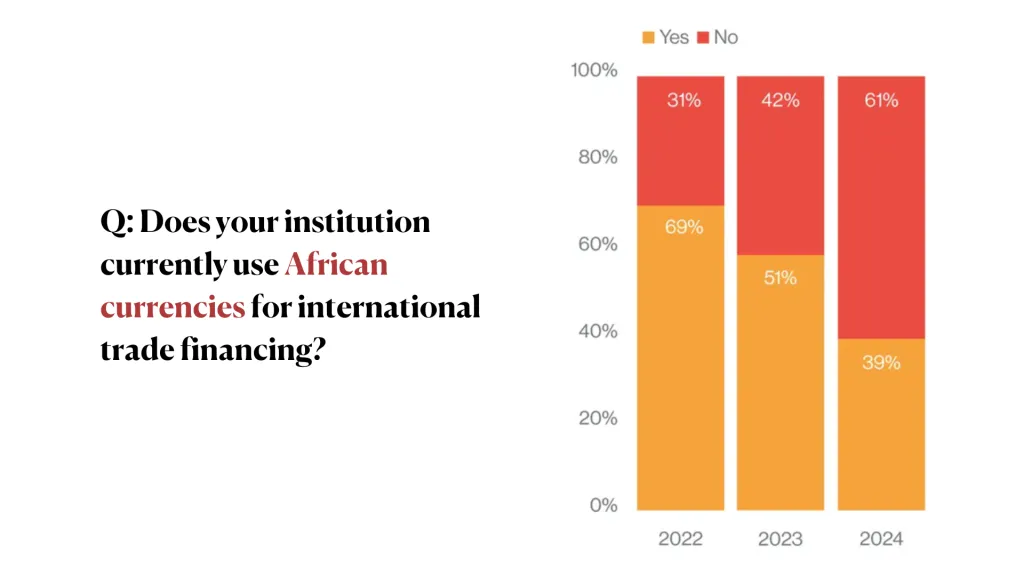

The 2024 Pan-African Private Sector Trade & Investment Committee (PAFTRAC) survey of African trade patterns found that only 39% of African businesses use African currencies to finance their cross-border deals, a big fall from the 69% recorded in 2022.

This is likely to be the result of wilder than usual currency fluctuations over the past few years as a result of post-Covid trade dislocation and the fallout from the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The depreciation of many African currencies against the dollar has made them less attractive for those receiving payments. The South African rand has been considered an African hard currency in the past but it too has experienced big swings in value in recent years.

Many parts of the continent have proposed creating regional or continent-wide currencies but relatively little progress has been made to date, although two connected single currencies already exist on the continent. The mainly francophone states of Central and West Africa each operate their own versions of the CFA franc. Covering six and eight countries respectively, they are backed by the French treasury and pegged to the euro.

A continent-wide single currency is the dream but will be very difficult to achieve, despite the support of various African leaders. Speaking at last June’s Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) Heads of State and Government summit in Lusaka, Kenya’s President William Ruto said: “Our people cannot trade without worrying about which currency to use. This, among other non-tariff barriers, is something we must urgently address so that our people can begin to trade together and integrate.”

At the annual meeting of the Association of African Central Banks in September, the AU Commissioner for Trade and Industry, Albert Muchanga, said: “We require effective and timely implementation of the macroeconomic convergence criteria to lay the groundwork for the establishment of the African Central Bank, and immediately after that, a single African currency.”

The Secretary-General of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Wamkele Mene believes that Africa is already moving towards a single currency, while some African banks are also on board.

The Head of Global Markets and Corporate Sales at Absa, Gerald Katsenga, commented: “A common African Union currency is critical if we are to eliminate some of the transaction costs related to intra-Africa trade.”

The continent spends almost $5bn a year on using non-African currencies, he added. Yet despite the benefits, the single currency has been an explicit goal ever since the Organisation of African Unity was created in 1963, so it is unlikely to happen any time soon.

A total of 63.33% of the participants in the PAFTRAC survey were keen to see the creation of a single African currency to alleviate currency exchange risks. Such risks were named by the survey participants as the biggest constraint on trade with other African countries.

However, huge challenges stand in the way of creating a single currency. Firstly, each participating country will have to ensure the convergence of various national economic indicators within specific parameters, such as inflation and public-debt-to-GDP ratios. The continent seems no closer to achieving these today than in 1991 when the Abuja Treaty called for the launch of the ‘Afro’ or ‘Afriq’ by 2023.

Secondly, national governments will be reluctant to give up control of their existing currencies and monetary policies even where the economic benefits have been demonstrated.

Monetary union would help reduce the cost of financial transactions, eliminate exchange risk and reduce transaction costs, helping to harmonise prices in the process, but this would take power away from national governments.

Regional currencies

However, the fact that the project is attracting so much discussion following the launch of the AfCFTA suggests that may now be a distinct possibility, however far off, rather than a vague aspiration. It seems likely that regional currencies will be set up first. Once these have clearly demonstrated the benefits of such projects, the impetus for a single continent-wide currency will grow.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC), East African Community (EAC), Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) and Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (Comesa) all have plans for monetary union leading to regional currencies, while the AU has a long-term goal of launching a single African currency as part of monetary union.

The EAC plan for a single currency has been repeatedly delayed, most recently in August, when it was pushed back to 2031 amid disagreement over which country should host the East African Monetary Institute, which is to serve as a precursor to the East African Central Bank.

Ecowas had set a deadline of 2027 for the creation of its single currency, the eco, but its member states are still a long way from achieving convergence criteria. In September 2024, the block decided to suspend its single currency plan because of a lack of progress but also as a result of the sudden departure of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger from the community.

For their part, those three countries say that they are considering creating their own currency in an effort to further break ties with France.

Some have suggested that other West African states should aim to harmonise their regulations and institutions to create separate Anglophone and Francophone West African currencies in the short term, with the aim of merging the two in the longer term.

Elsewhere, Southern Africa’s Common Monetary Area includes South Africa, Namibia, Lesotho and Eswatini but is heavily dominated by the region’s most advanced economy. SADC as a whole aimed to introduce its common currency, the Samu, by 2018, but that target has obviously been missed. All these initiatives face problems in cajoling members into meeting inflation, interest rate, fiscal deficit and debt targets.

Even once regional currencies have been launched, the next step may be to combine two or more regional currencies, or for one regional currency to gradually expand. Even if and when a continent-wide currency is launched, there is virtually no chance that it will cover all African countries in its first incarnation. As in the EU, each country will have to jump through a variety of economic and fiscal hoops before it is allowed to participate.

The new payment system

In the absence of new currencies, the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) offers an excellent means of reducing the currency risks associated with cross-border transactions.

Launched by the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank) and AU in 2022, it is a cross-border payment, clearing and settlement system that allows individuals, businesses and governments to make instant payments to complete cross-border transactions in more than 40 African currencies and international hard currencies.

Unstable exchange rates can witness the terms of a deal deteriorate between the conclusion of a contract and payment actually being made, so PAPSS should help by speeding the process up. More than 50 commercial banks have already joined it, including Absa, Ecobank, United Bank for Africa and Zenith, plus at least 14 central banks, including those in Malawi, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Zambia. Membership is still voluntary but more banks are expected to join in the near future.

It is hoped that PAPSS will also encourage African businesses to change how they do business. At present, cash in advance is the preferred means of payment, ahead of letters of credit, open account sales and documentary collection.

Cash in advance is less risky for exporters than letters of credit but is the least attractive option for buyers, so its continued heavy use deters intra-African trade. It is also often combined with free on board terms, which require a buyer to take ownership of cargo the instant it is loaded onto a vessel, truck or train, under which the buyer assumes financial risk if there is any loss or damage to the freight.

Absa’s Gerald Katsenga says: “The real challenge for African businesses lies in the payment set-up. When you do intra-African trade, you settle via SWIFT, where you have the costs of intermediary banks.

“If I’m in, say, South Africa and I do a transaction paying somebody in Ghana, my rands have to go via either Europe (the euro) or the United States (the dollar), and then come back into Africa as Ghanaian cedi. When we use PAPSS, it’s still a net settlement in hard currency, but without having to go via the euro or the US dollar.”

Africa is still many years away from having the political will or the monetary ability to make a single currency a reality. It took decades for the EU to harmonise the economies of its member states sufficiently to launch the euro. Yet currency and payment barriers are significant impediments to making the AfCFTA a success, so it is to be hoped that the PAPSS becomes universally accepted and that progress is made on creating at least one regional currency in the near future.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google