As the first African countries gained independence, their pioneering leaders were passionate about the struggle for unity and development. The idea of African unity and the need for an institution for African development can be traced to the “TNT Conference” held in Sanniquellie, Liberia, in 1960. It was called TNT after Presidents Tubman of Liberia, Nkrumah of Ghana and Sekou Toure of Guinea. They argued that without unity, Africa could not develop and pledged all their efforts to bring total independence to Africa.

The establishment of the African Development Bank (ADB) and the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was fraught with difficulties. There was a consensus that unity was vital for the future development of the continent. But there were disagreements over the speed of reform and the form a united Africa should take.

In 1960, Nkrumah called a summit meeting under the auspices of the King of Morocco in Casablanca. But only the leaders of Morocco, Ghana, Guinea, Mali and Egypt attended. Later that year, the other heads of state, recognising Tubman as the doyen of African leaders, persuaded him to call another summit, which he subsequently did in Monrovia in 1961. The two groups became known as the Casablanca and Monrovia Groups.

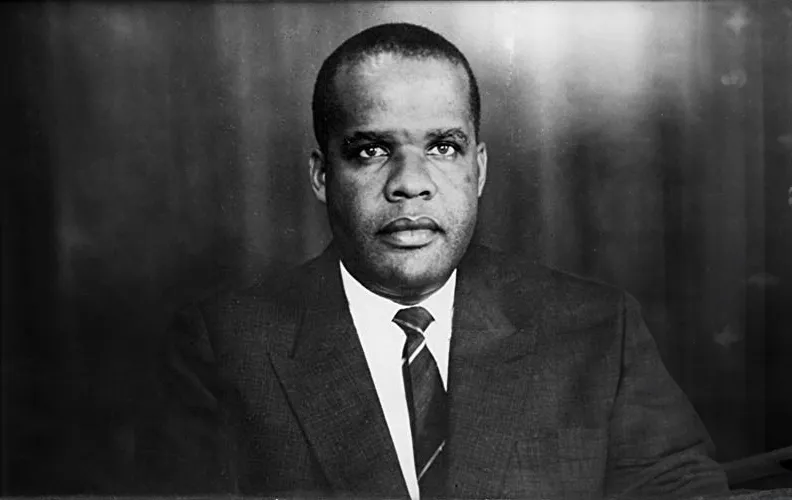

On the basis of the discussions in Monrovia, Tubman was asked to devise a charter for unity and development that would be acceptable to the whole continent. It then occurred to a young Liberian technocrat, Dr Romeo Horton, that an African Development Bank could assist in the continent’s quest for productive unity and development.

Tubman accepted Hortons proposal and mandated him to seek the endorsement of all the African leaders. When the concept was Dr Romeo Horton: thanks to him, Africa got a developm ent bank proposed to the World Bank, Horton and his associate at the time, E Clarence Parker, a Liberian banker, were met with disdain: “What will an African Development Bank do that the World Bank is not doing or cannot do?” In fact the only reason they managed to organise a meeting at all was because Dr Horton was a friend of the vice-president of the Import Export Bank who arranged a “10-15 minute” meeting.

The following year, at the second meeting of the Monrovia Group in Lagos, two draft charters – for the OAU and the ADB – were presented. They were endorsed by all the African leaders at the 1963 summit in Addis Ababa. The ADB charter was referred to the UN Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) for implementation. Horton was appointed chair of the Committee of Nine, set up by the ECA to establish the Bank.

The Committee recommended the appointment of the first president and a headquarters for the Bank. It also established a set of criteria for the headquarters: a stable government, a convertible currency, good communications, good living conditions, attractive climate and a city which would be suitable to foreign – African and nonAfrican – employees.

Sudan, interested in becoming the headquarters for the Bank, began lobbying. But in Horton’s judgement, Sudan did not fit the bill. Sudan persisted, however, exerting increasing political pressure on the other countries to back Khartoum as the headquarters. In the end, Horton recommended Abidjan, the capital of Cote d’Ivoire, as headquarters. Cote d’Ivoire met the Committee’s criteria. Furthermore, France was against the ADB and was putting pressure on its former colonies to reject the proposal.

Horton impressed upon the Ivorian president, Felix Houphouet-Boigny, the merits of the Bank and what it would mean to Africa and its future development. The Ivorian president eventually agreed to host the headquarters of the Bank.

Since its establishment, the ADB has had a chequered history. However, due to the efforts of the current president of the Bank, Omar Kabbaj, the ADB finds itself today in a unique position. It has $3bn to lend but is operating below capacity.

How can it increase lending and accelerate development? With a new president to be voted in next year, aspiring candidates must ponder the Bank’s position in five years’ time. Increased co-operation with the private sector; increased lending without compromising the solid foundations; and how to become the number one vehicle for African development are some of the pertinent issues the new president will have to tackle.

Interview first published on www.newafricanmagazine.com, October, 2004.

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google