In October last year the authorities in Beijing announced that they would be tightening export controls for some types of graphite, a critical mineral for the production of batteries and other electronics. The move, which China said was designed to “safeguard national security and interests”, raised serious alarm bells in neighbouring South Korea. The country’s major electronics companies, such as LG and Samsung, rely heavily on imports from China and other foreign markets to produce essential goods – not least semiconductors, which are central components of countless electronic devices and have become vital for the modern global economy.

In what is perhaps a sign of Africa’s growing geopolitical and economic importance, South Korea responded to this disruption by turning to the continent, and in particular Mozambique and Tanzania, both of which are home to significant graphite reserves.

Seoul has been investing heavily in developing diplomatic and economic relations in Africa, partly in anticipation of such developments. The continent is home to swathes of natural resources – such as graphite, silicon, and quartz – which have become increasingly valuable as essential components for semiconductor production.

Increased diplomatic energy

It is not just South Korea that has recognised how significant a role Africa could play in this industry. The United States, Europe, Russia, Saudi Arabia, India, and China are all committing more financial resources and diplomatic energy to the continent – with access to critical minerals a priority for all of them.

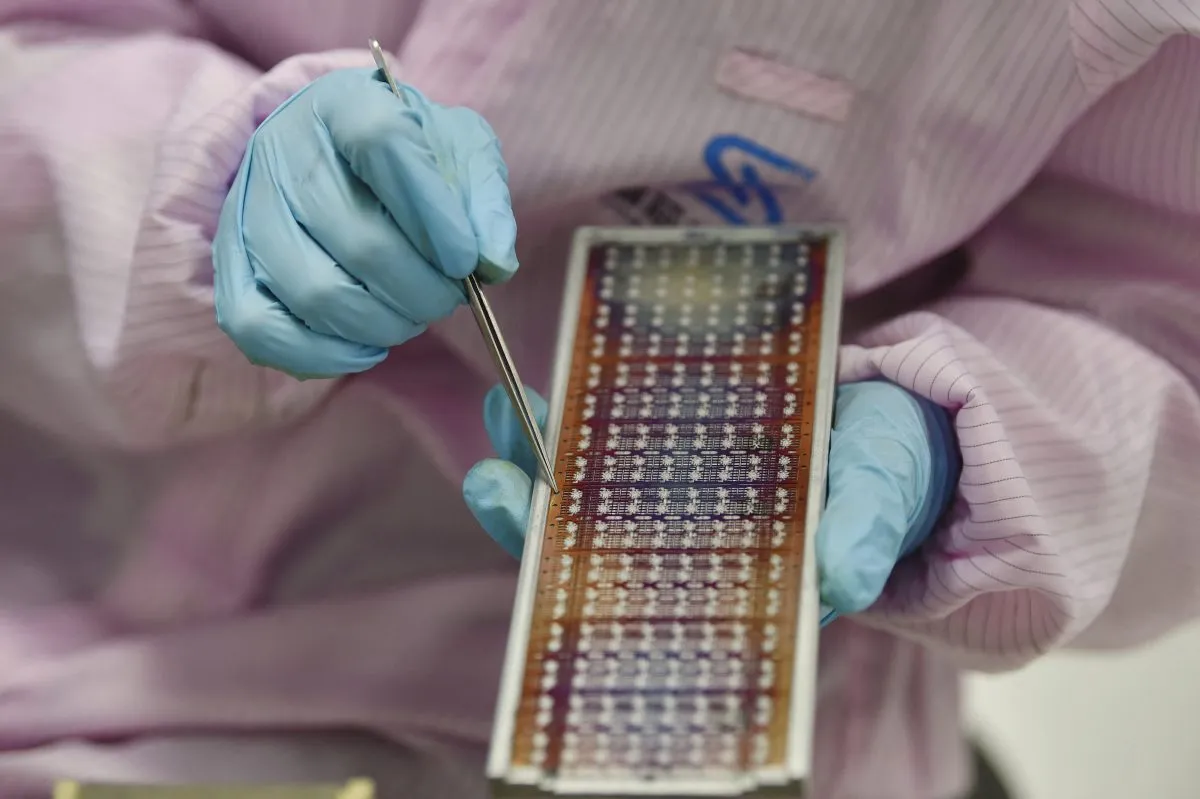

This increased interest and engagement is unsurprising because it is difficult to overstate how important the devices have become. Semiconductors, which are the core of everything from smartphones to defence systems and emerging artificial intelligence technology, now represent a $500bn global market. The total market cap for the top twenty customers of the leading producer alone, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC), easily surpasses $7 trillion.

The size of the industry and its critical importance mean there are undoubtedly economic opportunities for Africa. The continent’s share of the global market has, however, so far been limited. Despite having some of the world’s largest reserves of silicon and rare earth metals, African countries account for less than 1% of the global market.

Even those countries that do have valuable natural resources – such as South Africa, Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, and Nigeria – tend simply to export the materials to manufacturers abroad, rather than engage in more advanced, technical processes related to semiconductor production.

There are some notable exceptions. Cairo-based Si-Ware Systems, which closed a funding round of almost $9m in 2021, has emerged as a global leader in silicon-based semiconductor innovation and posted annual revenues of over $20m last year. In 2022, South Africa also managed to export a modest $25.9m worth of semiconductor devices. But on the whole, Africa currently lacks the capacity to conduct higher-value activities.

Nii Simmonds, non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington, tells African Business that “Africa has an opportunity to move up the semiconductor value chain.”

“Electric power deficiencies and a lack of industrial water supplies mean that Africa is not going to be in a position to make the most advanced semiconductors or chips anytime soon,” he says.

“However, there is definitely potential for African countries to be involved in things like research, design, testing and flash memory manufacturing.”

Research and development hubs

There have been some encouraging – albeit small – moves in this direction. South Africa, for example, has taken some early steps by establishing the Microelectronics and Nanotechnology Centre at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) in Pretoria, a research and development (R&D) facility focusing on semiconductor and chip production.

Kenya also appears to have ambitions in this field, with the government launching the country’s first semiconductor production unit in 2022 in the hope of developing advanced technological capabilities. However, investing in such initiatives, with the aim of stimulating the development of the industry and improving technical knowhow, needs capital that most African countries simply do not have.

Simmonds suggests that a potential solution to this problem would be for Africa to follow the model which was pursued by Southeast Asian countries in the 1970s and 1980s.

Foreign multinationals, primarily from the United States and Japan, were heavily involved in the development of the region’s consumer electronics industry. Global companies such as Sony and Hewlett Packard established manufacturing hubs and R&D centres in Southeast Asia and – owing to a favourable political and regulatory environment, a highly educated population and cheaper labour than was available in their domestic markets – shifted large parts of their operations to Singapore and other nearby countries.

Encourage multinationals to put down roots

Simmonds believes that African countries should seek to follow this example and that Western governments should also encourage multinationals to establish roots on the continent. In the geopolitical battle for influence in Africa and for access to resources, he thinks that this would be a powerful way for the West to differentiate itself from Beijing and to build more positive relationships in Africa.

“China has a focus on value extraction and imports as many minerals as possible from Africa and other emerging markets. It is also not bound by any environmental or governance frameworks,” Simmonds says. “The US and Western partners can promote more sustainable, mutually beneficial growth by creating incentives for major technology companies to move parts of their semiconductor manufacturing and R&D supply chains to African countries, just as they did with Southeast Asian countries in the 1970s and 1980s.”

He is encouraged that there has been progress on this front, although much more investment is still needed. Google has established a R&D technology hub in Accra, the Microsoft Africa Development Centre (ADC) has offices in both Nairobi and Lagos, while IMB Research has outposts in Johannesburg and Nairobi.

Simmonds notes that more such projects and investment could unlock significant economic benefits for Africa while strengthening the supply chains of the US and its multinational companies. “This would allow Africa to capitalise on the US’ need for more resilient supply chains, after supply chain vulnerabilities were starkly revealed during the pandemic,” he says. “This [US] administration’s flagship Inflation Reduction Act also includes provisions for establishing partnerships with strategic allies through investment in manufacturing at home and abroad. Africa, and its technology industry, can take advantage of this.”

An alternative to China

In terms of how Africa can best position itself in the global semiconductor and electronics industry, Simmonds also thinks that there is an opportunity for the continent to capitalise on the “China Plus One” strategy that more enterprises are adopting. This refers to the growing trend of businesses avoiding investing in China, in light of rising production costs and higher geopolitical risks, and instead committing capital to other emerging market economies.

“Particularly should Africa improve its governance conditions and offer a more stable environment for investment, the continent could benefit from companies wanting to diversify their supply chains to mitigate China-related risks,” Simmonds notes.

South Korea’s decision to replace graphite imports from China with those from Mozambique and Tanzania was one that Seoul was forced into; but more companies and governments could make similar moves proactively as part of broader “China Plus One” strategies.

These trends suggest there are plenty of opportunities for Africa to forge a greater, more valuable role for itself in global semiconductor supply chains. Challenges still remain – foreign capital will be required, and technical knowledge will need to be developed before African can conduct the highest value operations – but there are also compelling factors in Africa’s favour.

“Africa is at the geographical centre of global semiconductor supply chains and is home to many of the essential materials. It is where the world meets,” Simmonds says. “There is an opportunity for Africa to devise a winning strategy in this sector.”

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google