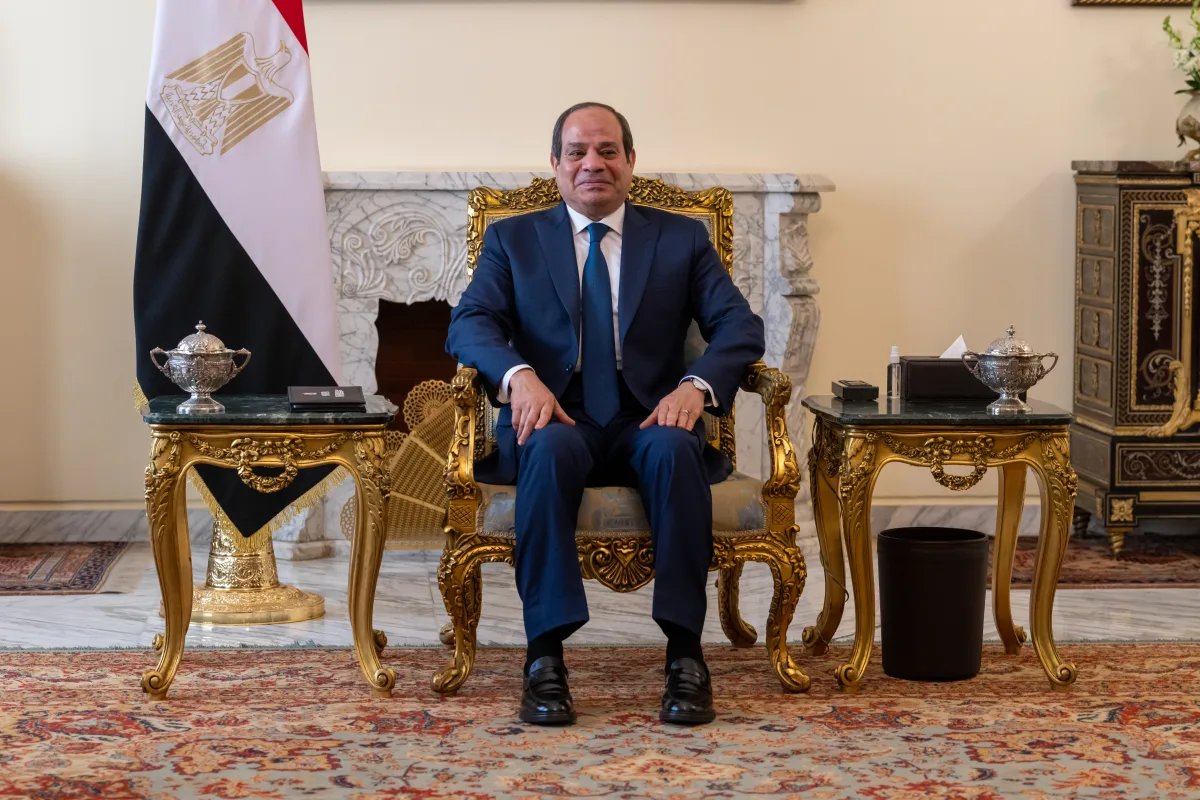

The confirmation that Abdel Fattah al-Sisi will serve a third term as president of Egypt could have important economic ramifications at a time when North Africa’s most populous nation is facing profound challenges on multiple fronts.

Sisi secured 89.6% of the vote on a turnout of 66.8%, according to the National Election Authority, in a December contest devoid of viable opposition which most observers saw as little more than a formality.

While critics hit out at the conduct of the polls, it is the economy, rather than politics, that is likely to be the defining challenge of his third term. Cairo’s difficulties have been bubbling for some time – not least because Sisi, a former army general who came to power in 2014 following a military coup against the Islamist President Mohammed Morsi the previous year, has allowed the Egyptian economy to remain dominated by the armed forces.

That choice has been compounded by external forces – Egypt’s economy suffered particularly badly during the coronavirus pandemic, when revenues from tourism, which stood at over $30bn in 2019, dropped sharply. This loss of international commerce also contributed to a steep fall in foreign exchange inflows into Egypt, leading to a severe shortage of US dollars.

Foreign exchange difficulties – amid a broader macroeconomic environment of higher interest rates, a stronger US dollar, and much weaker Egyptian pound – have also made it much more difficult and expensive for Cairo to service its enormous pile of dollar-denominated debt.

Given these challenges, in December 2022 Egypt received a $3bn bailout package from the IMF in order “to preserve macroeconomic stability […] and pave the way for inclusive and private-sector led growth”. These reforms included a liberalisation of the foreign exchange market, in the aftermath of which the Egyptian pound fell to record lows against the dollar.

Further reforms to financial markets in the country are needed to unlock more IMF funds, but Sisi was reluctant to oversee another devaluation of the pound prior to the election. This is both because of the negative symbolism of a declining currency, as well as the impact of devaluation on the cost of living. A weaker currency makes essential imports more expensive in local terms and therefore contributes to high inflation.

Tough choices ahead

But with the election now over, could Sisi be prepared to make the tough choices that the Egyptian economy needs?

Nouran el-Khouly, an economist at CFI Financial Group in Cairo, tells African Business that the economic challenges Egypt faces are serious – and perhaps likely to get even worse in the short-term.

“Given the challenging economic environment worldwide due to the repercussions of the pandemic and geopolitical tensions, Egypt, like its counterparts, is witnessing high inflation, pervasive economic uncertainty, high debt levels, a current account deficit, and large outflows of investments,” she explains.

“All these issues have caused a shortfall of foreign currency, which was further heightened due to the global adoption of monetary tightening.”

She is concerned that the ongoing conflict in Gaza, which is adjacent to Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, could further hit Egypt’s tourism industry and therefore worsen Cairo’s foreign exchange troubles.

Credit ratings agency S&P Global Ratings “expects a 10-30% drop in tourism revenues in Egypt, which could cost the country 4-11% of its foreign exchange reserves and lead to a decrease in GDP, to which the tourism sector contributes significantly,” she says.

As a result, she believes that one of the economic priorities for Sisi in the aftermath of the election will be “facilitating dialogue in Gaza to douse the flames of the conflict”. The President referred to the tension during an address after his election win was confirmed, branding the vote a rejection of the “inhumane war”.

However, even if the conflict in Gaza is resolved quickly and tourism revenues are not as affected as profoundly as many analysts fear, it is clear that Egypt requires more fundamental reform – both to satisfy the demands of the IMF and its international creditors, and to put Cairo on the path to long-term financial stability.

Despite this, el-Khouly thinks that it is too soon for Sisi to consider a further devaluation of the Egyptian pound or more market liberalisation measures. She says that “the Egyptian government may not be ready to let the Egyptian pound float immediately – they would probably prefer to do a gradual devaluation because the main priority now is to curb the inflation rate and restore price stability.

“A gradual devaluation would help attract foreign investors, in turn helping to reduce the foreign currency shortage in Egypt,” el-Khouly adds.

The search for creditors

Partly because of this reluctance, Egypt may look for other creditors willing to lend the country cash regardless of whether it undertakes financial reforms. El-Khouly predicts that Sisi will look “to diversify Egypt’s financing instruments other than taking direct loans from international agencies, such as by tapping into Islamic sukuks [shariah-compliant bonds]”.

While this could raise the risk of Egypt simply taking on greater piles of debt, without the accompanying reforms that international organisations such as the IMF insist on, el-Khouly thinks that Sisi nevertheless recognises the need for “structural reforms for a sustainable economy”.

She points out that “the government is improving the country’s productivity by enhancing the transportation routes, promoting digital transformation and green production, and focusing on value-adding products and services.”

Although Egypt faces several serious economic challenges, many international investors are confident that the longer-term prospects for the country could be bright – if only the government were finally able to move past the issues with which they have been dogged.

Charlie Robertson, head of macro strategy at FIM Partners in London, previously told African Business that portfolio managers could sense opportunities in Egyptian currency and fixed income markets if the government committed itself to devaluing the Egyptian pound again. Earlier this year, the Egyptian stock market hit record highs.

Long-term optimism

Meanwhile, many investors and analysts have expressed optimism that a country in close geographical proximity to the oil-rich Gulf markets, with a large and growing young population as well as good infrastructure, could emerge as an important manufacturing and production hub.

El-Khouly shares that optimism, despite the difficulties which the country is currently battling.

“The Egyptian government has introduced several reforms and initiatives to attract more investors into the economy, and it is succeeding,” she says.

“2023 has ended on a positive note for Egypt, with its annual core inflation rate at 35.9% in November 2023, down from 38.1% in October. It is expected to decline to 27.4% in 2024. The Egyptian stock market has achieved a historically good performance during this past month,” el-Khouly tells African Business.

“In the last financial year, the current account deficit improved by 71.5%. So I am optimistic with the Egyptian economic outlook,” she adds, particularly as the prospect of lower interest rates in the United States is raising hopes that debt-burdened countries such as Egypt will face lower pressures this year.

Will Egypt’s economic potential be realised? As Sisi begins his third term in office, Egyptians will be hoping that the government will at last be able to resolve the country’s short-term and structural issues – and thereby unleash an era of rapid and sustainable growth.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google