In 2001 Jim O’Neill, then an economist at Goldman Sachs, coined the acronym ‘BRIC’ in reference to Brazil, Russia, India, and China. He singled out these countries as fast-growing, populous emerging markets at similar stages of development with the potential to disproportionately shape the future of the global economy.

The four countries formalised their relationship in 2010 and on Christmas Eve at the end of the first decade of the new millennium, South Africa was invited to join the group. O’Neil, the father of the acronym, believed the country was too small an economy to include, but the geopolitical significance of expanding the continental coverage to Africa is only now outlining the structure of a new world economic order. South Africa’s accession added another letter to the acronym, establishing what we now commonly refer to as BRICS.

The BRICS group has come of age in the years since, emerging as the foremost economic rival to the G7 bloc of leading advanced economies with the potential to fast-track the transition to a multipolar world.

Growing economic heft

The BRICS countries have overtaken the G7 in terms of their contribution to global GDP, with the group now accounting for almost a third of worldwide economic activity measured by purchasing power parity. This position is growing and, according to the most recent estimates from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), China and India together are forecast to generate around half of global growth in 2023.

With economic size comes influence in international trade. China, the largest BRICS economy, overtook the US in 2013 to become the world’s largest trading nation. It has become the top trading partner of more than 120 countries across the developing and developed world, a coveted position previously enjoyed by the US for decades. Across the world’s 10 largest economies, China is the top trading partner of eight, and is the EU’s single-largest trading partner.

There is a clear positive correlation between economic growth and trade, especially in the modern era of efficiency-driven, just-in-time global value chains, so the BRICS’ rise has primarily been at the expense of the slower-growing G7. The latter’s share of global trade has decreased steadily as accelerated technology diffusion has shifted manufacturing output towards the Global South, and particularly across Asia.

The G7 nations still account for a sizeable share of global trade – thanks to their resilient purchasing power – but this has been on a downward trajectory, falling to around 30% in 2022 from more than 45% in 1992. Over the same period, the BRICS’ share has climbed from around 16% to almost 32%, with the largest leap forward coming between 2002-12.

The consequences of these shifts have already reverberated through the trade and economic arenas, but the significance of the BRICS’ maturation is much broader. In an age of great power rivalries and heightening international tensions, the use of economic sanctions and the weaponisation of the US dollar have propelled the BRICS into the geopolitical arena.

While trade between Russia and the G7 has fallen by more than 36% since 2014 under the weight of economic and financial sanctions, trade between it and the other BRICS nations has soared, increasing by more than 121% over the same period. China and India have become the largest importers of Russian oil following bans imposed by the EU. China’s trade with Russia hit a record of US$188.5bn last year, a 97% increase from 2014, and around 30% greater than in 2021. The surge occurred as Russia more than doubled its rail exports of liquefied petroleum gas as part of a drive to diversify its exports under the harsh sanction regime.

Despite sanctions, the resilience of export growth is sustaining Russia’s economic expansion, with output expected to grow by 1.5% in 2023, according to the IMF’s most recent forecasts. By opting not to comply with Western-led economic and financial sanctions, the solidarity of BRICS is a balm for Russia. The bloc has offered trade diversion and other relief to one of its founding members and, in the process, weakened the effectiveness of sanctions as a tool for advancing economic and geopolitical interests.

A multipolar magnet

Thwarting the sanctions regime has had consequences that reach far beyond the impact of the crisis in Ukraine. Bolstered by their success on the economic and geopolitical fronts, the BRICS group is increasingly viewed by a growing number of countries in the Global South as a more attractive agent of multilateralism than the Non-Aligned Movement, the forum of 120 countries (almost all of which are developing economies) that was founded in 1961 but which has largely faded into obscurity since the end of the Cold War.

The BRICS’ success and its strong economic prospects, underpinned by these countries’ rising middle class, have galvanised support from other nations. With the risk-reward trade-off of integration becoming more attractive, there is now considerable momentum behind expanding the bloc. More than 40 nations – including Algeria, Egypt, Thailand, and the United Arab Emirates, but also key G20 countries such as Argentina, Indonesia, Mexico, and Saudi Arabia – formally expressed their interest in joining the BRICS in the lead-up to its 15th summit in Johannesburg, South Africa.

If the effectiveness of trade diversion by BRICS nations in weakening the impact of Western sanctions against Russia is any indication, sanctions will only become less effective as a tool for advancing the economic and geopolitical interests of the G7 after the admission of new BRICS members. In a zero-sum global trading environment, the bloc’s expansion would also accelerate the diversification of demand away from G7 countries and reduce members’ exposure to future geopolitical risks. Indeed, the more members, the greater the network effect of the BRICS’ expansion.

Talks at the summit have the potential to shape the bloc’s trajectory and enhance its role in addressing emerging challenges, while accelerating the transition to a multipolar world. Speaking in early August about the summit, Anil Sooklal, South Africa’s ambassador-at-large to BRICS, highlighted its transformational potential: “BRICS has been a catalyst for a tectonic change you will see in the global geopolitical architecture starting with the summit.”

All eyes will be on South Africa as the leaders of the BRICS bloc deliberate over a wide range of issues that reach far beyond the group’s initial mandate, which was to encourage commercial, political, and economic co-operation among its members. The focus will be on the admission of new members, as well as trade and investment facilitation in a challenging global environment where the escalation of trade and tech wars – along with the “friendshoring” of supply chains – has increased the risk of global growth deceleration and a hard landing in China.

Major sources of disagreement with the G7 to be discussed include sustainable development in the climate change era, global governance reform (particularly in relation to the IMF), and an orderly process of dedollarisation. On the latter, more and more emerging economies are exploring ways to conduct trade in non-dollar currencies following the imposition of sanctions against Russia.

A growing number of experts, including senior US government officials, recognise that the aggressive use of economic and financial sanctions to advance US foreign policy could threaten the dollar’s hegemony. US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently emphasised this point: “There is a risk when we use financial sanctions that are linked to the role of the dollar that over time it could undermine the hegemony of the dollar.”

A new reserve currency

The significance of dedollarisation cannot be stressed enough in the context of a potential BRICS-issued reserve currency to be used by members in cross-border trade. While the BRICS nations – which collectively enjoy a comfortable balance of payment surplus – have the financial wherewithal to establish such a currency or unit of account, they lack the institutional architecture and the scale to sustainably achieve this end.

Even assuming that its members are fully aligned geopolitically and more inclined to co-operate than to compete, adopting a common currency presents several challenges. As the creation of the euro, now the world’s second largest reserve currency, illustrated, hurdles will include: achieving macroeconomic convergence; agreeing on an exchange rate mechanism; establishing an efficient payment and multilateral clearing system; and creating regulated, stable, and liquid financial markets.

The US was able to enforce the use of the dollar in the last century owing to its hegemonic position following the end of World War II, reinforced in the decades since by the size of the market for US treasuries, which are often considered to be the world’s leading reserve asset. If they wish to provide a competitive alternative, the BRICS countries will need to agree upon a state-of-the-art bond market. It would need to be big enough to absorb global savings and provide assets with low risk of default where surplus funds could be parked when not used for trade.

Reflecting on these challenges, Sooklal reiterated in July that a BRICS currency will not be on the agenda during the summit, though expanding trade and settlement in local currencies will be. In addition to reducing exposure to global volatility and transaction costs as well as geopolitical risks, BRICS countries are already yielding significant benefits from the use of local currencies in cross-border transactions. Their use is helping to sustain and boost cross-border trade between members, even amid a challenging operating environment of heightened geopolitical risks. It is also loosening the balance of payments constraints associated with dollar funding, bolstering local economies.

Although China and India may have diverging security interests, they each stand to benefit from the increased use of local currencies. BRICS nations are already using their own currencies for bilateral trade payment settlement, and Saudi Arabia is considering signing a deal with China to settle oil transactions in renminbi. Meanwhile India is expanding the use of local currencies for bilateral trade payment and settlement beyond the BRICS group, inviting more than 20 countries to open special vostro bank accounts to settle trade in rupees. In a history-making move, in mid-August India made its first oil payment to the United Arab Emirates in rupees.

Forging a new financial architecture

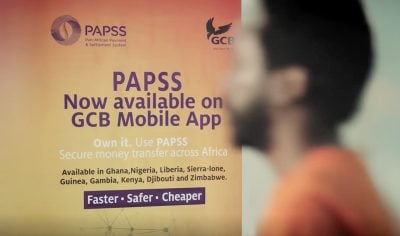

The good news is that the BRICS group already has the institutions they need to create an efficient and integrated payment system for cross-border transactions. The BRICS Interbank Co-operation Mechanism facilitates cross-border payment between BRICS banks in local currencies. BRICS Pay, a multi-currency digital international payments system, eliminates the need for “vehicle currencies” such as the dollar and the euro, in transactions among member countries, reducing costs dramatically. Lastly, the Contingent Reserve Agreement provides short-term liquidity support to member countries facing short-term balance-of-payment pressures or currency gyrations.

Furthermore, the New Development Bank (NDB), which is spearheading the creation of a common BRICS currency, intends to raise local currency financing to at least 30% of its portfolio by 2026, up from 22% currently. The NDB will also play a significant role in the collective effort to reduce the dollar content of cross-border trade and investment between BRICS nations. In the lead-up to the summit, the bank issued its first South African rand bonds earlier this month.

The two bonds, a R1bn ($53.1m) five-year note and a R500m three-year note, were oversubscribed, attracting R2.67bn of bids in total. Simultaneous efforts to strategically align the development of central bank digital currencies, which would promote currency interoperability and deepen economic and financial integration, augurs well for an orderly transition towards a multipolar reserve currency world in this digital-first era.

Membership expansion, which is expected to be one of the major outcomes of the 15th BRICS summit, will increase the risk of a divergence of interests and raise more coordination challenges – but it will also dramatically expand the group’s consumption power, with significant economic and geopolitical implications. Expansion will create scale and enhance the transition from bilateral to multilateral clearing, and ultimately towards a common BRICS currency. This will address one of the major challenges associated with the use of local currencies for bilateral trade payment settlement: the difficulty of deploying these currencies once imbalances arise. Lately, such challenges led to the suspension of bilateral trade arrangements that had allowed India to settle imports of Russian oil in rupees, with Russia accumulating billions of Indian rupees that it could not use.

Meanwhile, membership expansion will further weaken the effectiveness of economic sanctions and accelerate the multipolarisation of the global monetary order. The larger group will eventually include most members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries – increasing the shared benefits associated with the use of local currencies for cross-border transactions and further curtailing the volume of global trade conducted in dollars.

To be sure, the stickiness of institutional arrangements, along with the breadth and depth of US financial markets is such that dollar dominance will remain a key feature of the global financial architecture for some time. But following membership expansion, what Jim O’Neill once lumped together as a small group of fast-growing emerging markets could soon transform into a markedly powerful geopolitical coalition that will accelerate the process of dedollarisation and the transition to a multipolar world.

The BRICS’ 15th summit will be one of the most consequential in the bloc’s history, if not in the history of the world economy – the geopolitical map is being redrawn before our eyes.

A shorter version of this feature was first published in Project Syndicate.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google