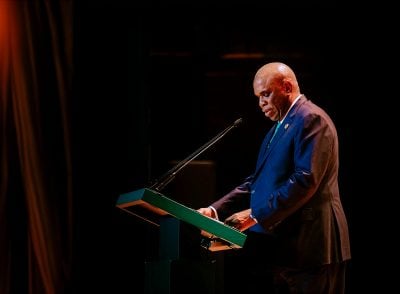

Alain Ebobissé, constantly crisscrossing the continent, is hard to pin down but I managed to catch him on his way back from India where he was looking at various infrastructure projects and seeking new partners to catalyse investments. “If there’s one lesson we can learn from the subcontinent,” he says, “it’s their speed of execution.”

This is what Africa50, the institution Ebobissé heads, was founded to do – increase and speed up investments in infrastructure. It was operational in 2016 to help bridge Africa’s infrastructure funding gap by investing in and mobilising private investments in infrastructure on the continent.

Its primary function is to bring together co-investors, project developers, African governments and financial institutions from Africa and overseas to invest in African infrastructure. It is quite prepared to invest during the riskiest part of a project, its early stage, and take it through to completion. It also invests in the expansion of developed projects.

In a little over six years, it has deployed capital in 20 countries, enabling over $5bn worth of investments. This first phase was really about developing proof of concept, says Ebobissé and now the institution wants to move at greater speed. “There are some big announcements coming up,” he says enthusiastically.

Africa’s infrastructure financing needs are estimated to be $130bn–$170bn per year, leaving an estimated annual gap of $68bn–$108bn. In 2018, of the $100bn invested in African infrastructure, only 2% was for regional projects (ICA).

That is a probably an underestimate. Nigeria alone estimated it should be spending $100bn annually for the next 30 years to close its gap.

The Acting Executive Secretary of UNECA, Antonio Pedro, has said that an extra $70bn is required when climate resilience is factored in. The success or otherwise of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and other continental incentives depends on appropriate infrastructure to facilitate trade, communication, innovation and growth.

Closing the gap

Africa50’s mandate is to help close that infrastructure gap by channelling direct public and private investment towards that purpose. Its focus is on medium to large scale projects that have the potential to deliver good returns for investors.

“The gap is huge but we are making progress,” Ebobissé says. While there are a lot of potentially bankable projects on the continent and a wealth of capital that is seeking exactly those projects, a lot depends on how the projects are structured.

“Sometimes, when you have risks that the private sector is unable or unwilling to take, you need to have risk mitigation instruments so that you have a bankable project,” he says.

“In a sense what you need to do is to provide comfort to investors and lenders so that they can recover their capital and make a decent return,” he explains. Africa50, he says, is all about developing bankable infrastructure projects in Africa to attract private investors.

And, Ebobissé says, Africa is immensely bankable. In fact, data from Moody’s indicates that the default rate on infrastructure is the second lowest in the world. But what Africa has to offer has to be talked up in order to change the often negative narrative around investing in Africa.

“There are differences in terms of the investment climate in different African countries,” Ebobissé accepts, “but there are a lot of success stories on the ground – some of which we have been involved in. We have to talk about those success stories; those projects that are delivering good impact and decent returns,” he urges.

Rapid turnaround of projects

Currently, Africa50 is involved in about 20 such projects around the continent. These include power plants in Egypt, Senegal, Nigeria, Cameroon, Madagascar and Mozambique; joint border posts in Côte d’Ivoire; data centres in Ghana and Kenya; a bridge in the Democratic Republic of Congo; Kigali Innovation City in Rwanda; and power transmission lines and broadband infrastructure in Kenya.

These projects, Ebobissé argues, have shown that it can deliver projects at speed. The challenge now is to demonstrate that it can do so at scale – it has to be able to deliver on some big ticket items in order to make a significant impact.

What is unique about Africa50’s approach is that it has chosen to be involved at the project development stage. Ebobissé admits that this is quite risky but insists that this allows it to get more projects to the bankable stage much faster and generate a healthy return.

This is in keeping with its character as a commercial entity. “We believe Africa is attractive. Even though there are some challenges, we can overcome those challenges to invest in projects that have an impact and also returns. And there is nothing wrong about making good money as long as you are making a positive impact,” he asserts.

The virtue of this approach was demonstrated in the Malicounda power plant project in Senegal, which Africa50 was asked to structure and make attractive to investors.

Ebobissé recalls: “We were able to do so reasonably quickly but most importantly, we were able to invest our equity into the project before the lenders were ready to fund it.

“In doing so we improved the project implementation timeline and we were able to implement the project faster than if we had done it the traditional way, where we wait for the lenders to get ready before we start construction.”

Coordination between African governments and the private sector is also extremely important in addressing the infrastructure gap, he points out. By structuring projects and allocating risk proportionately, governments are encouraged to follow through on needed projects.

“My experience is that once governments are comfortable, they are able to move faster than when they are cautious. This is the role we are playing at Africa50 – to make both the government and the private sector comfortable so that we can achieve project implementation as quickly as possible,” he says.

Fundraising initiatives

With only about a billion dollars committed capital from its government shareholders in hand, Africa50 needs to raise far more money to make greater impact. The aim now is to raise more money from institutional investors and a recently launched vehicle, Africa50 Infrastructure Acceleration Fund.

The need to achieve more impact is also the reason why Africa50 has chosen equity over debt instruments. According to Ebobissé, equity can enable Africa50 catalyse more private investment than debt.

African institutional investors, he says, are sitting on about $2tn of assets, a mere sliver of which could be applied towards infrastructure investment. Investment in infrastructure, including through Africa50’s instruments, he is convinced, would constitute a profitable and dependable proposition for these funds.

One such class of investors, pension funds however, might require regulatory changes to allow fund managers to invest in infrastructure funds. Despite this, Africa50 has had some success with pension funds across Africa.

“I understand governments are cautious because pension fund money needs to be managed in a very safe way. But we are going to advocate that governments should ease up some of those regulations to enable pension funds to invest a small portion of their holdings into African infrastructure through institutions such as Africa50.

“We will be able to show that this can be done prudently and that it will yield returns as well as impact.”

One intervention he is particularly pleased about is the ‘Room2Run’ initiative, executed in concert with AfDB and Japanese bank Mizuho, which was the first-ever synthetic portfolio securitisation concluded between a multilateral development bank and private sector investors.

It transfers the mezzanine credit risk on a portfolio of 47 AfDB non-sovereign loans in the power, transportation, financial and manufacturing sectors across Africa. Africa50 invested into Room2Run alongside Mariner Investment Group, a US investment firm.

It freed up $1bn on AfDB’s balance sheet that it can now apply to other projects, while delivering returns to investors, including Africa50 itself.

Another path to funding the infrastructure gap, Ebobissé says, is asset recycling. “We are recommending this to our government shareholders. Simply put, once they have assets that are producing revenues, they can recycle those assets to raise money which they can then invest in new projects.”

For African sovereigns in the midst of a debt crunch brought on by various global crises, this is a welcome intervention and Ebobissé says it is gaining a lot of attention.

No time to wait for perfection

The challenges of the moment also mean that governments are looking for non-traditional means of funding and Ebobissé predicts that there will be more public-private partnerships as a result.

For example, more credible utilities and tariff regimes in the power sector would mean that independent power producers would not need to procure sovereign guarantees against their investments.

“There are considerable pools of capital, including in Africa. It is important to leverage these and attract these institutional investors to African infrastructure investment,” he says.

This places an imperative on investors not to wait for the perfect project or the perfect conditions. Too often on the continent, investors, developers and financiers are looking for a gold-plated project, the perfect conditions and the perfect pricing.

“The culture at Africa50 is that if it is good enough, we do it. Speed of execution is important. We are not looking for perfect [conditions before investing]; we cannot have perfection in the imperfect environment that we are in.

We have to focus on the fundamentals and what is important. Once you get that done, you can move and correct course as the project progresses.”

“There is an imperative to move with speed. We cannot compromise on reputational risks or on the demands of environment, social and governance principles but we cannot wait for the perfect project to move forward. The cost of delay is too great,” he argues.

“African infrastructure is bankable and we have many examples of people making good money and can deliver back to the project. Our challenge now is to try to do a lot more of those projects faster and at scale. That is our challenge for the next few years,” he adds.

Africa50 will be hosting its General Shareholder Meeting on 4 July. There will be an Infrastructure for Africa Forum preceding the GSM, bringing together key players and financiers in the infrastructure space.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google