Addis Ababa had long said that it needed to strengthen domestic banks before inviting outside investment but it now appears to feel that greater competition will not overwhelm the country’s own financial service companies.

There is no doubt that Ethiopian banks currently underperform in comparison with those based in the rest of the continent. There were just two Ethiopian banks in the African Business Top 100 Banks 2022 survey: Commercial Bank of Egypt in 30th place and Awash International Bank in 85th.

The government has paved the way for reform over the past year by telling local banks to prepare themselves for deregulation and the arrival of new competitors.

Officials had previously suggested that foreign banks might only be permitted to operate in Ethiopia via joint ventures with local banks but they now seem likely to be allowed to apply for their own banking licences.

It has also been reported that a draft of the new banking legislation will allow foreign lenders to take stakes of up to 30% – and foreign individuals up to 5% – in Ethiopian banks. However, details of the final plans are still being finalised in the run-up to their publication in December. Potential investors will be keen to see whether all restrictions on profit repatriation are to be lifted.

Deregulation is likely to lead to profound changes in the Ethiopian banking landscape and some local financial service providers appear to be preparing for the influx. For example, microfinance company Amhara Credit and Savings Institution (ACSI) has now become Tsedey Bank, making it the largest private bank in Ethiopia with 500 branches across Amhara region.

In addition, it seems likely that there will be some consolidation among the 24 banks currently operating in the country. Reports within Ethiopia suggest that domestic banks have enjoyed a return on equity above 20% in recent years, much higher than the global average, but competition could drive this figure lower.

SMEs underfunded

There is little doubt that the Ethiopian banking sector as it stands is failing to serve the needs of the national economy, partly because state-owned Commercial Bank of Ethiopia (CBE) dominates the sector, with a market share of about 50%.

The limitations of domestic banks mean that it is difficult for Ethiopian small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) to trade with other countries. For instance, Ethiopia exported just $12m-worth of goods to Kenya in 2020, nine times less than moved in the opposite direction. Ethiopian sources also report that there is currently no method of transferring money between banks within the country.

Foreign investment should bring the digital revolution to Ethiopia. The development of digital banking and mobile money platforms has been slower in Ethiopia than in most other large African markets. Reversing this trend would boost the overall penetration of banking services, particularly in currently underserved rural areas.

The country’s biggest banks still overwhelmingly rely on big branch networks to serve their customers: Commercial Bank of Ethiopia’s 22m customers have access to 1,300 branches, while Awash Bank’s 566 branches cover 5m customers.

The liberalisation will of course have profound implications for the Ethiopian banking sector but should also provide great investment opportunities for banks based in other African states to secure market share in what is the second most populous country on the continent.

There are 121m Ethiopians at present, with the number growing by 3m a year, rising to a forecast 145m in 2030 and 205m by 2050. Throw into the mix the fact that Ethiopia had the world’s third fastest growing economy between 2000 and 2018 behind China and Myanmar, and it is clear why foreign banks are attracted.

Progress in telecoms sector

Banking sector deregulation is not guaranteed but it looks unlikely that the government will backtrack, particularly given the changes that are already being enacted in the telecoms sector and in the rest of the financial services industry.

Ethiopia was one of the last markets in the world to have a telecoms monopoly but state-owned Ethio Telecom – formerly the Ethiopian Telecommunications Corporation – now faces competition for the first time, thanks to the government’s decision to give Safaricom Telecommunications Ethiopia (STE) an operating licence.

As might be expected, Kenya’s Safaricom leads the STE consortium, which also includes the UK’s Vodafone, South Africa’s Vodacom, British International Investment and Sumitomo Corporation of Japan. It won its licence last year with an $850m bid.

Initial market response to its arrival suggests that foreign banks too may be able to exploit huge untapped demands in their sector. In its first week of operation in late August and early September, STE attracted 200,000 subscribers despite only launching in three regions: Dire Dawa, Haramaya and eastern Harari.

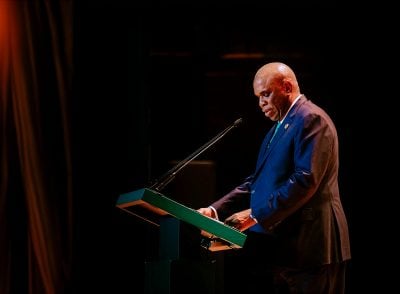

In early October, the Ethiopian government sanctioned the launch of Safaricom’s high-profile mobile money service M-Pesa in the country. The announcement was made at the official launch of STE in Addis Ababa in October, which was attended by Kenya’s President William Ruto and Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed.

Only Ethiopian companies were previously permitted to offer mobile money services, although they were slow to do so. Ethio Telecom launched its Telebirr mobile money platform as recently as May 2021 but attracted 4m users within weeks, so there is clearly plenty of demand for such services. Prime Minister Ahmed said the decision to allow M-Pesa to enter the Ethiopian market was “anchored on the understanding that our ambitious economic growth strategy is reliant on leapfrogging Ethiopia into the digital era.

“Expanding connectivity in every corner of the country is not only essential for providing access to telecommunication but also critical for addressing binding constraints in critical sectors like agriculture, healthcare, logistics, education, tourism and manufacturing,” he said.

As in the telecoms sector, Kenyan companies are likely to lead the way in entering the Ethiopian banking market. Equity Group and KCB Bank, both of Kenya, plus South Africa’s Standard Bank, already have representative offices in the country and look likely to be at the front of the queue for full banking licences.

At the STE launch, Ruto talked up the prospects of greater trade between Ethiopia and the rest of Eastern Africa, saying that the reforms were “integral to the momentum of progress taking place in our region”.

Outlook

There are some clouds on the horizon, including political and security problems, which may make foreign banks think twice about investing in the country. Government forces backed by Eritrean troops and local militia are fighting the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in the far north of the country. The TPLF led a coalition that ruled Ethiopia from 1991 until 2018 but did not accept the transformation of that coalition into the more centralised Prosperity Party, triggering the ongoing conflict that has devastated Tigray region.

Ethnic and regional tensions elsewhere in the country, coupled with severe restrictions on political opposition and civil society, could also threaten domestic stability. The greater freedoms that were promised when PM Ahmed came to power in 2018 have largely failed to materialise.

In addition, although the economy was able to grow at 6.2% a year even at the height of the pandemic, productivity growth is slowing, government spending and debt levels are both rising, and the proportion of the population living below the poverty line remains stubbornly high.

There is a shortage of foreign currency and the IMF forecasts that GDP will grow by just 3.8% this year – a reasonable level by the standards of most countries but a big drop on Ethiopia’s recent performance.

However, much of the government’s borrowing is directed at infrastructural projects, including in the power and transport sectors, which should lift the country’s long-term growth prospects. As a result, rising debt levels may not be quite as dangerous as many believe.

Indeed, the government’s new banking and telecoms sector policies may be intended to sustain the impressive levels of economic growth that have been achieved since the turn of the millennium. The tensions between its economic ambitions and continued high levels of state control should steadily result in the liberalisation of those sectors that remain highly regulated.

If the banking sector is liberalised as planned, it will be very interesting to see how the situation develops: in terms of the level of investment by foreign banks, the ability of Ethiopia’s biggest financial service providers to compete in a more open market, and the impact that this has on the provision of financial services and wider economic development.

Deregulation should make it easier for Ethiopian SMEs to access credit and for Ethiopian firms of all sizes to obtain hard currency, so the entire private sector should benefit.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google