In Black Ghost of Empire, Kris Manjapra lays aside the many myths that surround the historical facts of the emancipation of African peoples and makes a compelling contribution to the evidentiary basis for reparations.

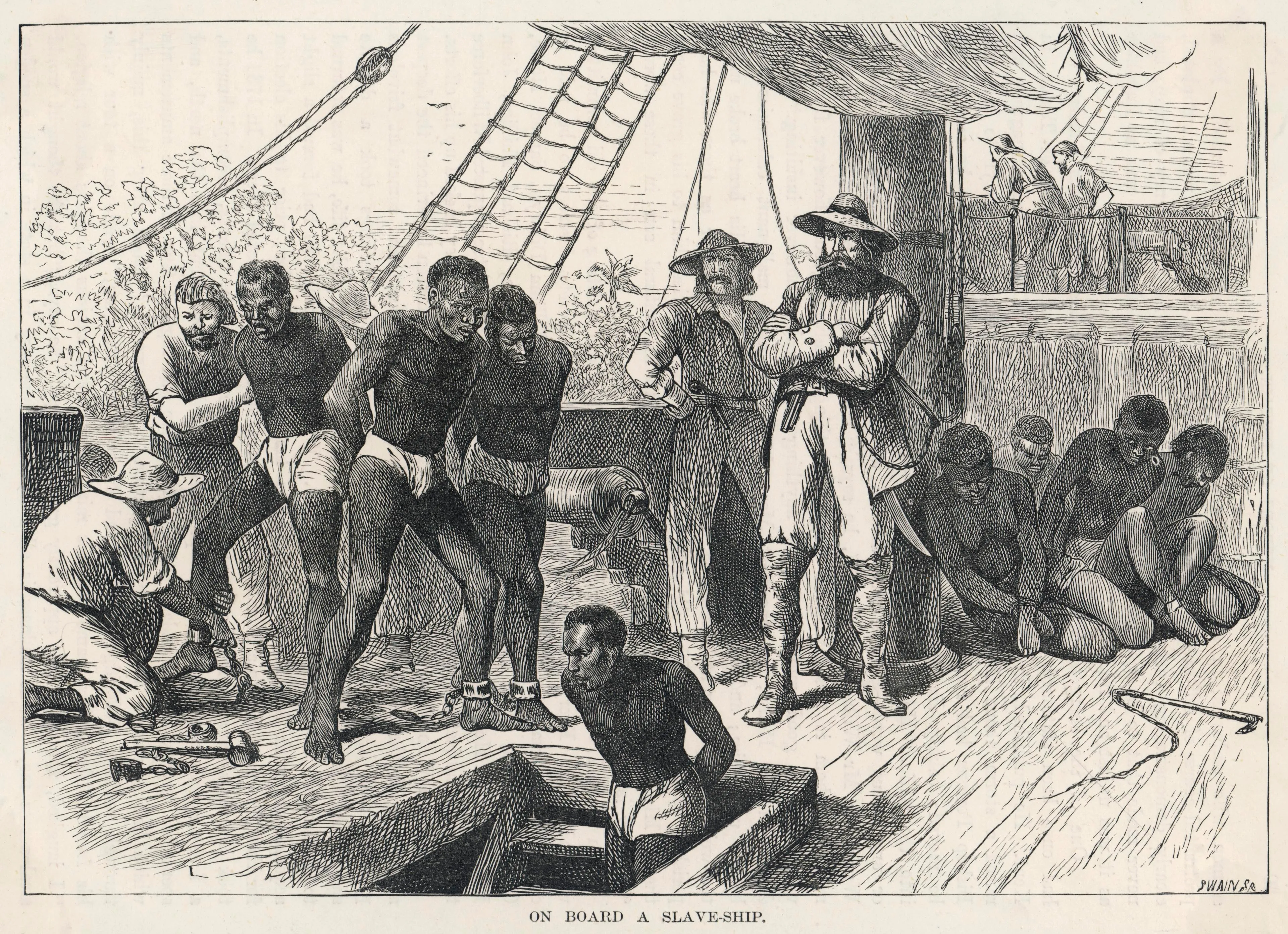

As Manjapra puts it: “Five hundred years of racial slavery designated African-descended peoples as devoid of human value. It stripped them of their personal and family names, obliterated their kinship ties, and assigned them a market price as atomised pieces of human property.

“Slavery swallowed millions of Africans into the bellies of ships, enumerated and inventoried them, transported them across the seas, and spat them out into slave markets across the Americas and Europe.

“It was an incalculably traumatic system of genocide, tearing families apart and alienating people from their own sense of themselves; forcing them to reconstruct life, joy, and family again and again. Slavery constituted a centuries-long war against African peoples. And the emancipations – the acts meant to end slavery – only extended the war forward in time.”

Indeed, there is a powerful argument that the legacy of slavery did not end with formal acts of emancipation and continues to reverberate around the globe to this day.

It is not just the Black Lives Matter movement calling for racial justice in the US and elsewhere that we can point to, but the enduring damage and economic marginalisation suffered by the descendants of the enslaved in other former slave colonies.

Manjapra’s powerful history puts him at the forefront of those arguing for a serious attempt at reparations.

Uprisings and revolutions

He comes to this conclusion by retelling the history of slave rebellions in the Caribbean, such as the exemplar of Saint-Domingue, now known as Haiti.

This is the western part of the island of Hispaniola, and it was bought from Spain in the 17th century by the French, who expanded and intensified slave plantation systems there until hundreds of sugar mills operated across the country.

In addition to sugar, European demand grew for “nutrients, intoxicants and other chemical compounds from distant lands”. By the 1770s, the author tells us, “Saint-Domingue had more than 800 sugar plantations, 2,000 coffee plantations, and 700 cotton plantations.

“It produced approximately 40% of all the sugar and 60% of all the coffee circulating in the whole Atlantic economy, more sugar per year than all the sugar colonies of Britain combined.

“The island’s sugar, cocoa, and coffee production generated more than one-quarter of France’s annual income. The wealth of Paris, Bordeaux, Nantes, and Marseilles came from the accumulated wealth of this slavery.”

Unsurprisingly, discontent grew among the enslaved as the economy devoured vast numbers of African lives and eviscerated the ecology in a headlong quest for greater output. Just 40,000 white property owners kept hundreds of thousands of slaves, who were subjected to the whip, torture and other horrors.

There had been a number of uprisings before, but it was Toussaint Louverture in 1793 who led a revolutionary army of African insurgents to the capital, Port-au-Prince, at the time of the French Revolution.

The French governor panicked and in haste declared the abolition of slavery in the hope of quelling the uprising and avoiding invasion by competing European powers.

Compensating the slave-owners

But the hasty abolition was far from the end of the story. Haiti secured its independence in 1804, but it was not until 1825 that this was recognised by France, and then only under the condition that the country pay “reparations” of 150m francs to the former slave owners.

The New York Times has estimated that payment of this “debt” and the associated interest has cost Haiti $21bn over time, locking the country into a cycle of impoverishment and underdevelopment. It took until 1947 for Haiti to finally pay off all the associated interest, which had been passed on to the National City Bank of New York (now Citibank).

While white abolitionists tended to decry plans for Haiti’s direct re-enslavement, they failed to recognise and denounce the indirect ways in which anti-blackness was being reconfigured through France’s insistence on a slave-owner compensation scheme.

But France was hardly the only slaving nation which linked emancipation to slave-owner compensation. Britain did exactly that too.

Manjapra, writing in the UK’s Guardian newspaper, recounts how as a result of a Freedom of Information request the UK’s Treasury revealed that in 1833, “Britain used £20m, 40% of its national budget, to buy freedom for all slaves in the Empire. The amount of money borrowed for the Slavery Abolition Act was so large (equivalent to more than £300bn today) that it was not paid off until 2015. Which means that living British citizens helped pay to end the slave trade.”

This gigantic sum of money was not paid to the victims of slavery, the slaves themselves, but to the perpetrators (the slave-owners).

Manjapra adds: “Other slave-owning states, including France, Denmark, the Netherlands and Brazil, would follow the British example of compensated emancipation in the coming decades. But the compensation that Britain paid to its slave owners was by far the most generous. Britain stood out among European states in its willingness to appease slave owners, and to burden future generations of its citizens with the responsibility of paying for it.”

Day of reckoning must come

In the US, too, real freedom for slaves was seen as a far-off, distant ambition rather than a realistic short-term goal, even by the abolitionists of the more liberal northern states.

Clarifying how the early years of post-civil war history in the US shaped that country’s attitude to race and blackness, Black Ghost of Empire illustrates how past injustices reverberate to the present day.

Manjapra tells how the US civil war is so often viewed as the struggle against the ruthless Southern plantation slavers by the Northern abolitionists. But the Northern abolitionists, under the “heroic” leadership of Abraham Lincoln, had a somewhat underwhelming vision of emancipation.

For Lincoln and others, the whole issue of the liberation of African slaves was seen best as a gradual move towards an eventual freedom rather than an overnight breaking of the shackles of black servitude.

The same is true for practically all European countries, who for so long clung on to the benefits of slavery and delayed the reckoning that many, including Manjapra, feel one day must come.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google