Melissa Cook was driving through a high-end residential district in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, in 2010, when she saw a colossal Turkish embassy under construction. Erected all over the building site were billboards for Turkish Airlines.

“They were opening embassies all over the continent,” says Cook, managing director of Africa Sunrise Partners, a business research company. “The government was making a big visible splash.”

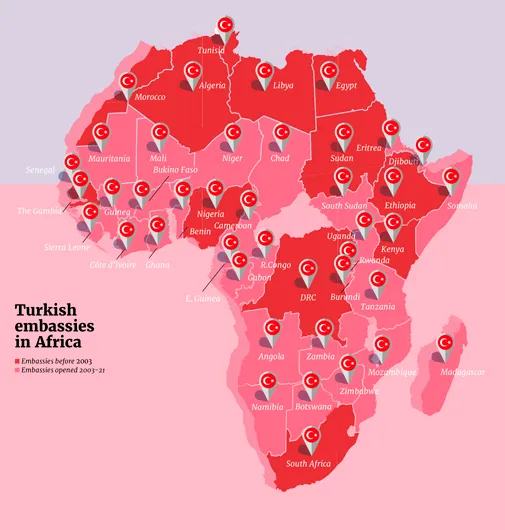

That building spree has taken the number of Turkish embassies in Africa from a dozen in 2009 to 42 today. This year, it will open its 43rd, in Guinea-Bissau.

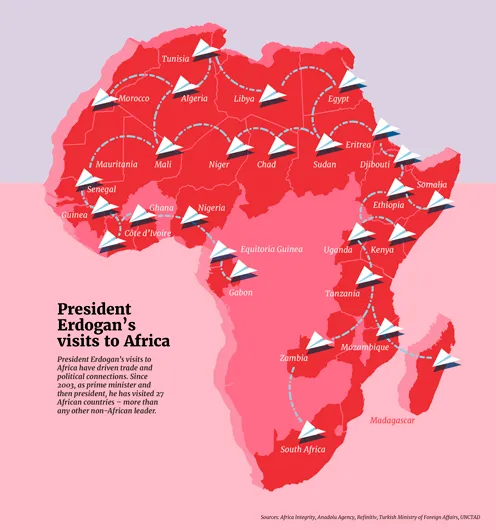

The breakneck embassy construction is a sign of Ankara’s rapidly growing presence on the continent. Its primary architect is Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey’s president, who has sought to remodel Turkey as an “Afro-Eurasian state”; a model for the Islamic world and an alternative to the West, which, in his mind, has surrendered its moral authority.

What began with economic outreach, experts say, has progressed into a complex Africa policy encompassing business, aid, diplomacy, culture and military support.

Today, Turkish fingerprints are all over Africa, from the Kigali Arena in Rwanda, east Africa’s biggest stadium, built by a Turkish construction firm, to an Olympic swimming pool in Senegal, a colossal mosque in Djibouti and Turkish military hardware on Libya’s battlefields. But while most African countries have welcomed the new partnership, experts wonder about the long-term ambitions behind Erdogan’s Africa strategy.

“It is fair to argue that Turkey’s initial engagement with Africa was provoked by economic incentives,” says Ali Bilgic, an expert in Turkish foreign policy at Loughborough University in the UK. Today, though, “it is not possible or advisable to separate Turkish economic, political, humanitarian, and military objectives.”

Trade between Turkey and Africa has ballooned from $5.5bn in 2003 to more than $26bn today, according to Turkish officials. Erdogan – who has visited more African countries than any other non-African leader – wants trade volume to double to $50bn in the coming years.

“President Erdogan’s main objective is to enlarge overseas trade and investment,” says Ugur Yasin Asal, an assistant professor of politics at Istanbul Ticaret University. “Turkish investors are seeking to make cost-efficient business operations in Africa,” he says, buoyed by the low cost of raw materials and labour.

“Turkish companies are used to operating in challenging places,” such as Iraq, Syria and Central Asia,” says Cook. “It’s good for the continent, without some of the political baggage and the opaque financial structures that come with the Chinese.”

But the engagement also has a political dimension, allowing Erdogan to portray Turkey as a proactive alternative to a negligent West. When the coronavirus pandemic hit the continent early last year, Erdogan saw an opportunity, and sent respirators and masks to Africa.

New dawn in the Horn

Such engagement with Africa symbolises the dawn of a new era for Turkey. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, Ankara focused its attention on its immediate neighbours and Europe.

“Turkey was built on the ashes of the Ottoman empire,” says Elif Comoglu Ulgen, Turkish ambassador to South Africa. “It was only when we approached the end of the 1990s, and with the end of the Cold War, that Turkey really opened up its eyes and mind and heart to the rest of the world.”

In 2005, when Erdogan was prime minister, the Turkish government announced the “Year of Africa”, and Ankara was accorded observer status by the African Union. Since 2009, Ankara has engaged with African countries, big and small, at feverish speed. It is looking to compete in Africa with established powers, from the US and France to China and wealthy Gulf states.

The ties soon began to take on an increasingly commercial aspect. In 2012, a landmark $1.7bn deal was signed between Ethiopia and Yapi Merkezi, a Turkish construction giant, to build a 400km railway connecting eastern, central and northern Ethiopia to the port of Djibouti.

That deal is now the norm, with Turkish companies, from energy to construction, active across Africa. Today, total Turkish investment in the continent stands at $6.5bn, officials say. The main trade and investment sectors are construction, steel and cement, followed by textiles, household goods and electronic devices says Asal.

More than a third of Turkey’s overall investment in sub-Saharan Africa – roughly $2.5bn – has gone to Ethiopia, which is fast becoming the centrepiece of Ankara’s Africa push. With a population of over 100m and an ambitious leader with regional designs in prime minister Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopia is the gateway to the Horn of Africa, a strategic region guarding some of the world’s most important shipping lanes.

Turkey’s 225 active firms employ more than 20,000 Ethiopians. Trade between the two nations amounts to $650m annually, with Ethiopia exporting agricultural commodities and importing industrial and pharmaceutical products from Turkey. With strong annual GDP growth prior to the pandemic, Turkish investors and business owners see Ethiopia as a winner amid a prolonged economic slump at home.

“Among sub-Saharan African countries, Turkey has some of the oldest relations with the people and government of Ethiopia,” says Yaprak Alp, Turkey’s ambassador in Addis Ababa, who notes that Turkey is now the second largest investor in Ethiopia, after China. “As we always like to put it, our bond with Africa is more similar to that between siblings than friends,” she says.

Turkey’s involvement in the Horn of Africa has already drawn Ankara into competition with rich Gulf states. At its narrowest, the vital Bab-el-Mandeb strait, a key shipping lane for oil, is just 16 miles wide. Over the water from Djibouti lies Yemen, where Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been waging a bruising campaign against Iran-backed Houthi rebels.

“Middle Eastern political rivalry and security dynamics have been exported to Africa, especially the Horn of Africa,” says Federico Donelli, a scholar at the University of Genoa specialising in Turkey’s Africa policy. “As a result, Turkey, like other regional actors, increased its military presence in the area.”

On February 15, Demeke Mekonnen, Ethiopia’s deputy prime minister, visited Ankara to open a new embassy building. This came shortly after Qatar and its Gulf neighbours the UAE and Saudi Arabia settled a dispute that had seen the small Gulf kingdom blockaded for three years. Turkey sided with Qatar throughout the dispute, supplying food and diplomatic support and increasing its military presence in the country.

While the consequences of the rapprochement are unclear, it will redefine the geopolitics of the Horn and could leave Turkey more isolated in the region, which could explain the clear desire to reaffirm ties with Ethiopia.

Turkish ambitions in East Africa stretch beyond the Horn. In East Africa, Rwanda teems with Turkish entrepreneurs. In the past decade, Turkish companies have invested about $400m in the country and some of the largest energy and construction tenders have been won by Turkish contractors.

“The Turkish health and transportation sectors seem to be the clear winners for now,” says Bilgic. “However, it is reasonable to expect that the construction industry and defence industry might follow.”

Connecting the continent

Turkish Airlines connects sub-Saharan African countries with each other and the rest of the world, boosting business ties and tourism, and increasing Turkey’s popularity across the continent. Today the carrier flies to 51 destinations in 33 African countries, 26 of them in sub-Saharan Africa. As recently as 2003, it only flew to North Africa.

“From South Africa outwards, everyone was flying Turkish Airlines. It was a game-changer,” says Judi Nwokedi, COO of Tourvest, a Johannesburg-based tourism group and secretary general of the Black Business Council, which advocates for South African businesses. “When Africans started travelling through Istanbul, they really fell in love with it.”

South Africa is today Turkey’s biggest economic partner in sub-Saharan Africa, with bilateral trade of $1.3bn in 2019. Still, Ulgen, the ambassador, notes that “there is a big unexplored potential between our countries.”

Officials insist Turkish businesses, drawn by enormous untapped markets on the continent, are already beginning to profit from the Africa outreach, in part because of Ankara’s multi-pronged approach comprising economic investment, diplomacy, humanitarian assistance and military support.

This “very unique model” ensures “that they know Turkey better, that they see Turkey as a country not coming to the continent with any colonial baggage. We are here on the continent with a win-win strategy,” says Ulgen, who says that “Turkish entrepreneurs are not necessarily guided by the Turkish authorities.”

Success and failure

But some countries have seen a sharper edge to Turkey’s presence. Since 2019, Turkey has provided military equipment and troops to the UN-recognised government in Libya, which has fought a civil war against the rebel forces of Khalifa Haftar, a general who has the backing of the United Arab Emirates and Egypt, in a bid, experts say, to secure influence in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Ankara has also signed a string of arms deals with African countries. Kenya recently spent $73m on armoured vehicles from Katmerciler, an Izmir-based manufacturer, and intends to deploy them against al-Shabaab militants. Other recent sales, to Uganda and Tunisia, are part of Erdogan’s plan to make Turkey self-sufficient in defence by the Turkish republic’s centenary in 2023.

However, no country better exhibits the multifaceted nature of Turkey’s push into Africa than Somalia. According to the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency, TIKA, Somalia was among the biggest beneficiaries of Turkish largesse in 2019, alongside Sudan, Niger, Djibouti, Chad and Guinea.

In 2011, amid a brutal famine, Erdogan made a watershed visit to Mogadishu, becoming the first non-African leader to visit the capital in almost 20 years.

Although the trip was humanitarian in tone, a comprehensive Somalia policy soon took shape. Since the trip, Turkey has poured an estimated $1bn into Somalia, where Turkish transport infrastructure, hospitals and schools have proliferated. Last year, Erdogan’s government paid off $2.4m in debts owed by Mogadishu to the IMF. Outside Mogadishu, Turkish personnel train Somali government soldiers.

Turkey’s largest overseas base is near Mogadishu, Turkish firms operate Mogadishu’s sea port and airport, its markets bulge with Turkish goods and in 2012, Turkish Airlines became the first international carrier to fly to the city in 20 years.

Other gambles have been less fruitful. In 2017, Erdogan signed an agreement with Sudan’s long-term dictator, Omar al-Bashir, to restore the architectural heritage of Suakin Island, a historic Ottoman trading post on the Red Sea, and renovate its port, provoking fears in Egypt and Saudi Arabia that this would lead to the establishment of a Turkish military base.

But Bashir was toppled amid nationwide protests in 2019, and the current civilian-military transitional government is re-establishing ties to the West, including signing a historic rapprochement with the US this year. It remains to be seen whether Turkey can continue to wield its once significant influence in Khartoum.

Turkey’s Africa policy nevertheless has seen rising trade and commerce matched by growing diplomatic influence. Erdogan presents Ankara as a benevolent alternative to the European powers that colonised the continent, a stance echoed by the country’s ambassadors.

“We believe in the approach ‘African solutions for African problems’ and support this in any way and form we can,” says Alp, the ambassador to Ethiopia.

Turkish officials are happy to promote their compatriots, insisting that the quality of Turkish projects is superior to that of the Chinese. “Our trade is as quick and as practical as the Chinese but quality-wise, some of the countries find it much more the quality they look for in the West,” says Ulgen.

Today, Turkish tourists bring revenue to businesses across the continent, while South African tourism to Turkey surged from 15,000 arrivals in 2016 to 79,000 in 2019. Tourism and cultural relationships are a “very good lever to then work on trade and commerce,” says Nwokedi, who has engaged intensely with Turkey on behalf of African entrepreneurs.

Today, she says, Turkish restaurants, popular for their music and belly dancing, are a common sight in South African cities. DStv, a leading South African content provider with a footprint across the continent, has a channel dedicated to Turkish content. “Turkish soap operas have a huge following in Africa,” Nwokedi says. “That redefined the way in which people began to see Turkey.”

Erdogan’s ambition

Some remain sceptical about the long-term African ambitions of Erdogan, a strongman who is widely viewed as a wily and ruthless political operator. “Over the past few years, Turkey’s foreign policy has increasingly become a means to pursue domestic policy goals,” says Donelli. African countries should beware the nationalism at the heart of Erdogan’s political philosophy, critics say.

“There are economic motivations behind the engagement in Africa,” says Donelli, pointing to the vast markets for construction, manufacturing and military hardware. These sectors, he says, “are closely intertwined with the [ruling] AKP’s political elite.”

While Turkey has grown at an impressive rate since 2000, economic vulnerabilities, external challenges and concerns over Erdogan’s authoritarian tendencies have undermined its performance in recent years. GDP growth, which had been running for years at over 5%, fell to 0.9% in 2018 as a result of a currency crisis provoked in part by concerns over central bank independence among investors.

Turkey’s domestic economic woes might make African countries an even more attractive proposition for Turkish investors in the hunt for growth markets.

Nevertheless, Turkey’s economy is expected to emerge from a prolonged slump this year – exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic – and grow as much as 4% on the back of retail sales and manufacturing. Erdogan, for his part, promised a new market-friendly era in November.

Bilateral trade, business ties, investment and political cooperation might have surged in recent years but experts say Turkey does not yet rival the major players on the continent, from the US and China to oil-rich Gulf states in the Horn.

Playing the long game

“In terms of size and capabilities, Turkey’s role in Africa should not be overestimated,” says Donelli. “At the same time, Turkey has certain characteristics that make it a valid alternative to traditional and emerging powers.”

Ankara is playing a long game in Africa, combining investment, aid and military sales to secure lasting relationships.

“There is no end in Turkey’s approach to Africa,” says Ulgen, the ambassador in Pretoria. Her predecessor was accredited in 10 African countries, but with the rapid opening of embassies, she covers just three. That will be reduced to one, she says, with plans for the white crescent and star of the Turkish flag to one day flutter above embassies in the tiny landlocked nations of Eswatini and Lesotho.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google