As the Chinese authorities scrambled to respond to Beijing’s first coronavirus outbreak in 50 days in the middle of June 2020, locking down residential compounds and sealing off a seafood market after at least 200 fell ill, an unruffled President Xi Jinping broadcast to African leaders to express solidarity in their own fight against the virus.

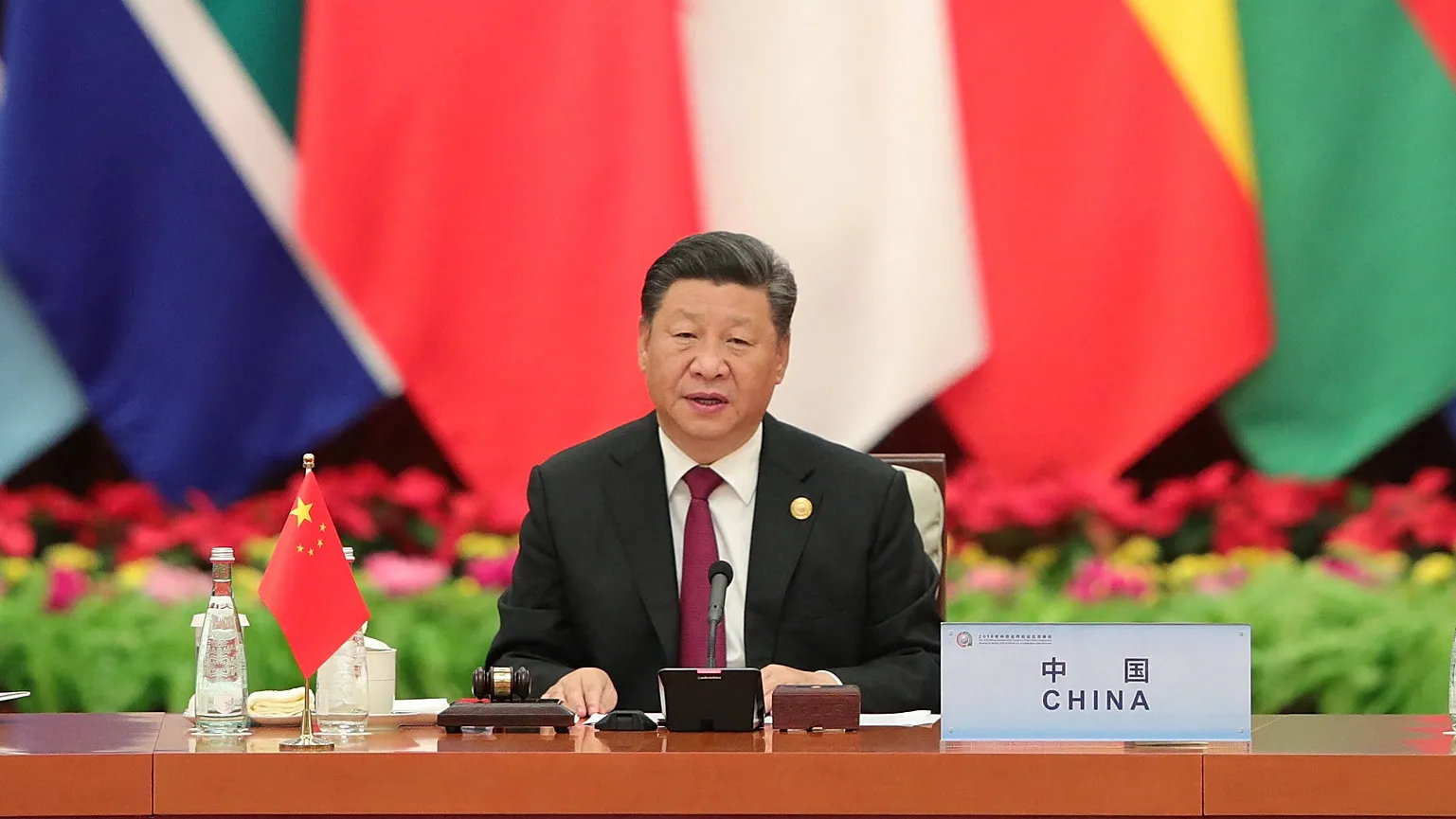

Appearing before a row of African flags on 17 June 2020, Xi lavished praise on the joint efforts of his African partners and deployed military metaphors to promise that Covid-19 will strengthen China’s economic and diplomatic ties with the continent.

“China and Africa have offered mutual support and fought shoulder to shoulder with each other. China shall always remember the invaluable support Africa gave us at the height of our battle with the coronavirus. In return, when Africa was struck by the virus, China was the first to rush in with assistance and has since stood firm with the African people… No matter how the international landscape may evolve, China shall never waver in its determination to pursue greater solidarity and cooperation with Africa.”

While Xi’s speech offered a reassuring dose of rhetoric for his African audience, it was also peppered with policy announcements. He promised that China will extend debt support to distressed African partners by cancelling interest-free loans that are due to mature by the end of 2020, pledged to work with the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative for the poorest countries and urged state-owned banks to show flexibility with their loans.

That offer was a recognition that the Covid-19 pandemic and the extraordinary global economic fallout it has wrought offer the most significant challenge yet to the health and stability of a China-Africa relationship bathed in warm words but underpinned by billions of dollars in investment and loans.

The pandemic has decimated Africa’s fragile economic assumptions, sapped Chinese demand for the commodities that support its leading economies, and forced the implementation of growth-eroding lockdowns. The World Bank predicts that GDP growth in sub-Saharan Africa could fall from 2.4% in 2019 to between -2.1% and -5.1% in 2020.

That is causing African policymakers to cast a nervous eye towards the continent’s debt pile, swollen by hundreds of billions of dollars in loans from the Chinese government, banks, and state-owned enterprises. Without debt support, unaffordable payments on the vast portfolio of loans from China and other wealthy nations could lead to a series of chaotic defaults by individual African countries.

China’s economic problems

Meanwhile, China itself is facing a daunting economic reckoning after years of expansive growth. Its status as Covid-19’s Ground Zero and the cost of unprecedented population restrictions have forced the government to abandon its official GDP target for the first time since 1990 – the IMF predicts it will grow by just 1% in 2020 compared to 6.1% in 2019.

The flagging outlook and a damaging US-China trade war have spurred doubts over whether Chinese policymakers will continue to plough billions of dollars into African projects with limited immediate upside.

“On both the demand and supply side we’re going to see a huge detrimental impact. The fiscal space for African governments is becoming increasingly constrained and it’s very unlikely they’ll be able to pay back existing debts let alone take on new ones,” says Yunnan Chen, senior research officer in the development and public finance team at the Overseas Development Institute.

“On the supply side China is going to have to confront a growing economic recession at home. The war chest of foreign reserves it had over the previous few decades that it was able to slosh around in developing countries is going to be a lot more limited and prioritised for domestic needs.”

While the relationship may be poised for a reset, it could offer an opportunity for the partners to place relations on a more sustainable footing by reordering debts, shifting towards mutually beneficial trade and foreign direct investment, and rethinking Africa’s debt model.

“There has been a shift in the tenor of the relationship even in the last 10 years where what used to be an economic relationship primarily based on the resource trade has shifted towards infrastructure and a political and strategic relationship. It remains in African leaders’ interests to have China as a powerful partner, but that era of debt-dependent finance is coming to a close,” says Chen.

Renegotiation time

While analysts are in broad agreement that the pandemic will hasten the decline of easy Chinese credit in Africa, there is little consensus around the appropriate timing or structure of Chinese debt relief.

The scale of the issue is obscured by a dearth of quality data. The Chinese government does not release official data on Chinese loan finance, export credits, or official development assistance on a regional or country basis, but Johns Hopkins University’s China Africa Research Initiative calculates that the Chinese government, banks and state-owned enterprises lent some $152bn to the continent between 2000 and 2018, some of which has been repaid. The World Bank estimates that China accounts for 17% of African debt.

Those loans take on a variety of forms, from official development aid disbursed by Chinese government ministries to commercial loans extended by Chinese private banks, and are not evenly distributed – oil-exporting Angola is estimated to have borrowed 30% of the signed Chinese loans disbursed to Africa.

Against this labyrinthine backdrop, President Xi’s offer, which includes cancelling interest-free loans due to mature in 2020, joining multilateral efforts for the poorest countries through the G20 and holding “friendly consultations with African countries according to market principles to work out arrangements for commercial loans with sovereign guarantees” appears a modest opening gambit rather than a definitive solution.

The offer is an attempt to give African countries vital breathing space until the pandemic is contained, says Justin Yifu Lin, Dean of the Institute of New Structural Economics at Peking University and a former chief economist at the World Bank.

“The Chinese government is realistic and also pragmatic. It understands the need for some kind of new arrangement to postpone some of the repayment, and the Chinese government understands six months is not enough. We need to give the countries with debt some time to come back to a normal situation before they can consider the repayment of the capital or interest.”

The immediate cancellation of interest-free loans is likely to chime with the demands of many African governments whose priority is to free up fiscal space rather than comprehensively negotiate tangled legacy loans.

“What the majority of African governments have been focusing on is the debt servicing issue, they’re interested in fiscal space so they’re not necessarily interested in full cancellation. Cancelling the interest-free loans is helpful because it means next year they don’t need to worry about that portion of their debt service,” says Hannah Ryder, chief executive of consultancy Development Reimagined.

Little hope of cancellation

Those hoping for more extensive support, including the renegotiation of commercial and concessional loans – the latter extended on terms substantially more generous than market rates – are likely to be disappointed.

According to research by Yun Sun, a nonresident fellow in the Africa Growth Initiative at Brookings, such concessional loans frequently comprised more than 50% of commitments made by China at the headline FOCAC summits with Africa dating back to 2006, only dropping to 25% in 2018. The diverse interests of creditors – more than 30 Chinese banks and companies have loaned money to African governments – makes renegotiation of these loans much more challenging, and they are rarely cancelled outright.

“In brief, on China’s debt relief for Africa, the world is looking at a long process of bilateral renegotiations, debt restructuring, and refinancing instead of a rapid, blanket, and comprehensive solution,” writes Sun.

In April 2020, Deborah Brautigam, director of the China Africa Research Initiative, wrote in The Diplomat that it was a “myth” that China frequently cancels debts, and argued that most cancellations were limited to “interest-free, foreign aid loans that had reached maturity without being fully paid off.”

Such loans amount to less than 5% of Chinese lending in Africa. Problematic loans are also reported to go through an onerous process involving staff from Chinese government ministries and state-owned lenders before being written off – easy debt renegotiations with China are another myth, Brautigam writes.

ODI’s Yunnan Chen agrees that cancellation is unlikely to be on the agenda in many cases:

“It’s likely that on a lot of these debts that China has incurred, they’re not going to make their money back. China Exim Bank and a lot of Chinese institutions already accepted even before the pandemic that there were some projects that shouldn’t have been financed and there will be a lot of bad debts.

“But this acceptance doesn’t extend to blanket generosity and saying we’ll just call the whole thing off. These loans were extended for commercial purposes and Chinese institutions are still there to make as much money back as possible… What is likely to happen I think with respect to China and the bulk of concessional and commercial loans which makes up a huge proportion of Chinese debt in Africa is that there will be some flexibility.”

“Most of China’s debt is for investment purposes… those kind of assets are productive assets and so when the situation returns to normal they will generate revenues. What China sees is a temporary pressure, so it proposes to postpone repayment,” says Lin.

Keys to success

Any successful renegotiation is likely to be on a case-by-case basis – a process in which shrewd African governments overseeing credible projects can vie for more generous terms rather than apply for a blanket write-off. In 2018, China agreed to restructure some of Ethiopia’s debt, including extending repayment of a loan from 10 to 30 years for a $4bn railway linking its capital Addis Ababa with neighbouring Djibouti – a process in which Ethiopia successfully wielded a “great deal of agency”, according to Chen.

With Chinese policymakers and lenders coming under increasing fiscal pressure as economic constraints weigh on the domestic market, there is mounting pressure to prioritise projects that can deliver returns or achieve defined strategic goals. A critical railway project in a strategic partner like Ethiopia is deemed to reach that threshold.

“Domestically [in China] there’s a constituency who continue to say where are our priorities and why aren’t we building our economy? A positive response by African governments can help to make the case but what the Chinese government increasingly needs to do is make a stronger economic justification for this kind of engagement. What really matters is not necessarily the amount or type of debt, what really matters is how growth-inducing these projects are and there’s a case to say some projects will face challenges through Covid but there’s others where the business case becomes stronger, like rail projects for example,” says Hannah Ryder.

Africa intends to complete viable projects and China has several financing options to support them, says Arkebe Oqubay, a senior minister, special adviser to Ethiopian prime minister Abiy Ahmed and co-editor with Justin Lin of China-Africa and an Economic Transformation.

“From China’s perspective they will look at completing the projects, they may explore combining commercial loans with concessional loans or adding some grants… models like public private partnerships will be more likely because they are less risky to African governments and will help develop new projects. It’s likely ongoing projects will be completed without delay and new projects will come with new modalities of financing – I don’t think [all financing] will freeze.”

Trading places

While China may hold the cards when it comes to loan refinancing, a fundamental shift towards alternative forms of economic engagement may be required to move the relationship forwards. Although Africa has soaked up billions of dollars in Chinese loans and investment over two decades, African trade with China remains heavily tilted towards precarious resource exports from a small number of commodity-rich economies.

The pandemic’s disruption of global supply chains could offer a renewed opportunity for Chinese foreign direct investment into more productive export-oriented sectors of the African economy such as manufacturing and agriculture, says Oqubay.

“Many countries have seen how vulnerable value chains are so the possible outcome of this is in beginning a diversification from Asia to Africa and Latin America. There is also an accelerated momentum that regional value chains will also be strengthened. One of the key weaknesses of trade between China and Africa is that although the volume has increased there’s a major imbalance – it’s mainly machinery and high value-added goods coming from China while African goods are mainly non-value added. On the trade side I think the Chinese government will take additional measures to encourage imports from the continent.”

Ryder agrees that the crisis offers an opportunity. “You have pessimists in China but you also have people who think this is a point where we should be investing more into the rest of the world and accelerating what they are doing. With regard to getting manufacturers to shift out of China, there had not been much of a shift in to Africa as yet – there had been specific countries like Ethiopia, Senegal, Rwanda attracting Chinese investment – but it’s possible there’s a bigger push because of diversification.”

On both trade and debt renegotiations, African governments should “compare notes” with their peers to forge a healthier and more sustainable relationship with China going forwards, says Ryder.

“I think most [African governments] don’t feel they’re in a debt trap but where they are expressing concern is on trade. They want to get more exports into China and are really pushing on that agenda starting in 2018. Some are much more interested in FDI from China than loans from China. They need to really learn the lessons from the past and be cautious on the specific terms and conditions for all those things and exchange notes, just as they need to on loans.”

Listen to our podcast on China-Africa relations

African Business podcast China-Africa relations with Jinny Yan, Chief China Economist, ICBC Standard Bank

This article originally appeared in the July 2020 issue of African Business magazine.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google