Opening the elegant new six-lane toll bridge stretching cross Dar es Salaam’s Kigamboni Creek in April, Tanzania’s President John Magufuli called it “liberation” for citizens.

It represents a $135m investment by Tanzania’s National Social Security Fund, the state-run pension fund, and government. China Railway Construction Engineering Group built the 680-metre bridge with China Railway Major Bridge Group and say it is the longest cable-stayed bridge in East Africa.

It is also Tanzania’s first toll road – which residents say is worth paying for as it makes their lives easier. The development will lead to new residential housing and is hoped to boost tourism in the country.

The World Bank estimates Africa should spend $93bn – 5% of gross domestic product (GDP) – each year on infrastructure and the African Development Bank (AfDB) notes a $50bn financing gap to reach this. Local and international pension funds can help fill the gap.

The Bright Africa report by consultancy firm RisCura says that at the end of 2014 assets under management by pension funds across 16 major African markets amounted to $334bn. Some 90% of assets were concentrated in four countries: South Africa (with $258bn) Nigeria, Namibia and Botswana. Assets had grown more than 20% a year in East Africa and 25%–30% a year in Nigeria over the previous half decade.

Potential to drive growth

Pension funds mostly invest in local fixed-income bonds, with regulation a key driver of asset allocation. But as RisCura argues, pension funds are ideal to drive inclusive growth and social stability, including through investing in longer-term projects such as infrastructure: “Local institutional investors lend credibility and a measure of validation, and often serve as a catalyst for greater external interest. Local investors also allow global peers to leverage local knowledge and networks.

With longer investment horizons, pension funds can serve as anchor investors for infrastructure and social development projects,” says the report. South African pension funds lead the way, partly spurred by rules that allow them to invest 10% of assets through private equity.

The Government Employees’ Pension Fund (GEPF) with R1.6 trillion ($111bn) assets under management in March 2015 reported it had committed R62bn towards “unlisted and developmental assets” in the previous 12 months, including Touwsriver and Bokpoort solar power projects in South Africa; MainOne data and broadband telecommunications in West Africa; pan-African power generation through Aldwych Power; N3TC which operates and maintains 420km of South Africa’s N3 highway; and two hospitals.

Other investments listed include $21.6m into private airport concession TAV Tunisia through the Pan-African Infrastructure Development Fund (PAIDF) managed by Harith General Partners. GEPF invested $2.6bn into the first PAIDF fund by March 2015 and pledged up to R4.2bn for the second by 2020. Five other pension funds also invested in the $630m PAIDF I fund, which will last 15 years and invested into more than 70 African projects. PAIDF 2 recently announced first close after raising $435m, again with pension funds as key investors.

South Africa’s Eskom Pension and Provident Fund (EPPF) in 2014 invested $30m into infrastructure projects through private-equity house Abraaj, based in Dubai, as well as mobile-phone infrastructure through London’s Helios. EPPF chief executive Sbu Luthuli says “We have to diversify” and wants to put more than $100m into infrastructure projects – 1.2% of its total R120bn assets (as of June 2015). GEPF said that it had invested 1% of its assets into African equities outside South Africa at March 2015, compared to a target of 5% (R80bn).

Financial institutions and multilateral lenders are looking to speed up the process. For instance, the AfDB created the Africa50 fund with target capitalisation up to $10bn and says it has secured $500m. For the second round to $1bn it is targeting institutional investors, including African and global pension funds. Kenya’s government and parastatals such as Kengen are leading the way in selling local-currency bonds to finance infrastructure.

The network is growing. Harith works with Asset and Resource Management Company in Nigeria to invest in West African infrastructure and is setting up a $1bn COMESA Infrastructure Fund with PTA Bank for eastern and southern Africa.

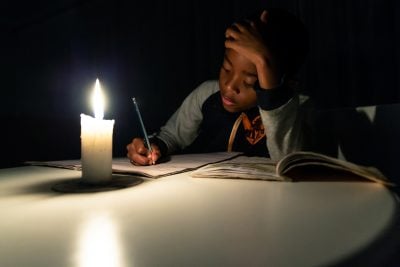

In June Harith and its Aldwych arm announced links with Africa Finance Corporation (AFC) to create a $3.3bn power portfolio, supplying 30m people across 10 countries. Andrew Alli, president and chief executive of AFC, says: “By working together we can deliver tangible benefit for Africans, switching their lights on and stimulating positive economic growth on the continent.”

But it’s not always that straight-forward. In February, Nigeria’s minister of power, works and housing, Babatunde Raji Fashola, called on the country’s pension funds, which manage some N5.8 trillion ($18.4bn), to invest more in infrastructure and other development projects. However, later in the year, newspapers reported that no infrastructure projects had been put forward that met the legal requirements of the 2015 regulations on investment of pension fund assets, including a minimum value of N5bn for individual projects and award through competitive bidding to a concessionaire with a good track record.

The Nigerian Labour Congress expressed members’ fears: “The thought of using our pension fund for investment in public-sector infrastructure development is highly frightening given the well-known penchant for mismanagement inherent in public-sector institutions in Nigeria … It is therefore immoral and careless to subject such fund which is the life-blood of workers to the itchy fingers of politicians, no matter how well intentioned.”

Despite the worries, confidence in governance is growing and attention is switching to building the supply of projects. As RisCura’s report notes: “In many countries, assets are growing much faster than products are being brought to market, limiting investment opportunities.”

Projects typically go through several stages, starting with feasibility studies to create a “bankable” project; then building or developing the project; and finally operating it once it is established, for instance collecting the tolls on a highway and fixing holes. The last stage is usually the least risky and most suited for pension-fund investors.

The Africa50 fund follows other initiatives in funding early-stage projects in order to boost the supply and mobilise more financing for later stages. Kigamboni bridge took more than two decades. Africa’s fast-growing pension funds need a faster pipeline of investible and well-run projects.

Tom Minney

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google