In Kenya’s remote western Siaya County, thousands of cheering villagers crane their necks to watch a bulldozer carve a trench through the red earth.

The ecstatic response is mirrored across East Africa as construction teams move between outlying villages and provincial towns, bringing previously ignored communities a much-needed infrastructure boost.

But this is no charity project with lofty goals of bringing clean water to a parched continent. London-headquartered Liquid Telecom deploys the bulldozers, and the trenches are pathways bringing terrestrial fibre cables to the heart of the continent.

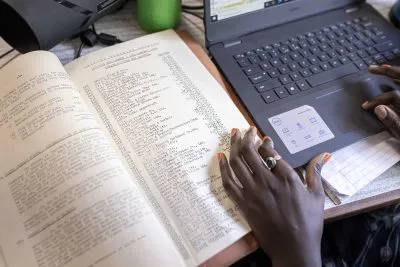

“We’re taking fibre to remote areas that I think never expected that they’d ever see it…they totally understand it’s about education, information and employment,” says Nic Rudnick, the group’s Zimbabwean chief executive, explaining the ecstatic and occasionally chaotic scenes.

“What we’re trying to do now is give those villages along the route access to high speed broadband.”

That vision sits at the heart of Liquid Telecom’s plans for the next phase of its growth. After vaulting formidable natural obstacles, bypassing reluctant wildlife and locking horns with hesitant regulatory authorities, the firm has established a 20,000 km fibre-optic network stretching from Cape Town to Kampala, focused largely on South, East and Central Africa.

The challenge now, says Rudnick, is to utilise that network to directly reach the great unconnected mass of would-be consumers. Despite rapid progress made by infrastructure providers and mobile telecoms firms, high-speed access remains a distant dream for the majority of households and small businesses on the continent.

According to a 2014 report from the International Telecommunications Union, only 19% of Africans are online – less than 10% of the world’s total internet population.

“The challenge now is to put the real internet into people’s hands instead of just putting it into the cities where they’re living – we now want people to start experiencing the results of what we’ve built up in the last few years,” says Rudnick.

Having initially focused on connecting businesses, February’s successful $150m capital raising spurred an ambition to connect 100,000 households by the end of the year. That remains on track, and the firm will likely double the figure by the end of 2016, says Rudnick. Allowing remote villages access to a superfast network that runs just metres past their houses is a key plank in achieving that goal.

But connecting homes to the grid represents only the start of Liquid’s ambitions, which stretch far beyond the construction of infrastructure and place the firm in direct competition with some of the biggest names in international media.

Rudnick is now focusing on the rollout of ipidi tv, a video-on-demand service which will deliver African-produced content alongside international shows from the BBC, ITV and other big-name broadcasters.

The plan may sound ambitious, but it is not without risk. African customers with a taste for expensive American dramas and a reasonable internet connection can already seek out international providers such as Netflix and HBO, while local rivals such as South Africa’s ShowMax are also feeling their way around the market.

Nevertheless, Rudnick says that ipidi’s support for African producers, and the backing of Liquid’s superfast network, gives his service the edge.

“In Africa the vast majority of content is still coming from offshore. This should be quite an exciting product because for the first time in Africa you’ll be able to pay locally and have the best international content but also the best local content all delivered over your fibre network.”

The competition may be intense, but the regulatory hurdles could be even more so. For Rudnick, who fought alongside Strive Masiyiwa, founder of Econet Group – which owns Liquid Telecom – in the tense legal battles to open up Zimbabwe’s telecoms sector, the picture remains frustratingly mixed.

While some countries have shown no interest in regulating the emerging digital services sector, others have enforced onerous broadcasting restrictions or denied access to firms until they’ve drawn up a new set of rules.

“One finds oneself in a whole new realm of regulation that one hopes is not there but soon discovers is…The frustrating thing is that you’ve got over-the-top players from elsewhere in the world whose services are available over the internet, but if you want to produce those services locally and look into what authorisations are required, often it’s not clear,” he says.

Regardless of the uneven regulatory picture, Liquid Telecom’s ambitions have captured the attention of capital markets keen to uncover pan-African firms with access to an emerging consumer class.

In September, Strive Masiyiwa claimed that Econet Group has dismissed ‘multibillion’ dollar bids for Liquid Telecom in recent months, and is likely to seek a listing for the firm in 2016.

Rudnick remains tight-lipped over those plans, but says that contrary to media reports, the listing may not be confined to a European stock exchange.

“Well, there are still some decisions to be made, so I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s Europe over Africa, it may well include Africa and I think some of the final detail of that is still being worked through, so let’s see what happens.”

In the meantime, Liquid has targeted a raft of deals to connect the continent’s largest mobile service providers with its network. In September, the firm inked a deal with Bharti Airtel, who will use Liquid’s transmission network to launch 3G and 4G services for its customers. Rudnick says that more deals in the sector could follow.

That potential burst of activity is likely to complement, rather than replace, the frenetic construction of new fibre on the continent. West Africa is the next possible area of expansion for a company unafraid to experiment in new regions. Indeed, Rudnick says that the firm is merely scratching the surface of what is possible.

“I don’t think we’ll ever stop building. I sometimes get asked where the exit is and my answer is, we’re just beginning. Africa is a huge continent, its people are to a large extent unconnected, so we’ve still got a long way to go.”

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google