Financing and regulation have held back mass transit systems in Africa.

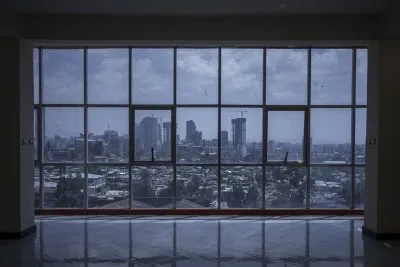

Since the start of the year, commuters trapped in Addis Ababa’s traffic gridlock have seen passenger trains humming along raised lines above the city – a glimpse of a future outside of the endless traffic jams.

Construction of the city’s $475m metro began in 2012. The testing phase is now under way, and the passenger launch is set for May. Its two lines run for a total of 32km, with underground and overground sections, 39 stations, and two operators – the Ethiopian Railways Corporation and Shenzhen Metro. It is expected to carry 60,000 passengers a day, and even that may not be enough to keep up with demand.

The metro is the first of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa outside of South Africa – although others are still in the planning stage. Nigeria’s commercial capital of Lagos intends to build 57km of lines; in Kenya, the government’s Vision 2030 includes plans to build an integrated 167km road and rail transport system linking the capital Nairobi’s 3.4m people with neighbouring towns.

Light rail is on the agenda in Ghana too, but the long-planned $1.5bn monorail project for Accra is yet to approach fruition.

Dr Nigel Harris, managing director of leading rail experts the Railway Consultancy, cautions that metro rail projects are not always economically viable and need to meet a tipping point before the investment becomes worthwhile. Harris defines this as 1m people with adequate incomes. “Unless you have enough people with money to travel, you don’t make a lot of money,” he says.

But with 2.5m people needing transport in Addis Ababa daily, and the relatively low cost of electricity, Ethiopia believes its investment is safe.

“Ethiopia has been able to mobilise economically viable financing from domestic and external sources. The rate of return in the project clearly shows the project will be technically and economically viable,” a spokesperson at the Ethiopian Embassy in London says.

The challenges for rail projects, Harris says, are the need for a conducive regulatory environment, and the capital needed to keep them running. “The main thing with railways is you need to maintain them, and that needs money.”

Investment in rail infrastructure is, however, a tool to achieve economic growth in the long-term, Harris says. “You’re not going to get your money back in less than 25 years if you’re lucky. But there are great social benefits, and that is what Ethiopia has realised.”

Gabriella Mulligan/Alexa Dalby

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google