What is capitalism? And is it good? Richard Seymour argues that capitalism, with all its flaws, is nevertheless the only system that delivers a wealthier, longer and healthier life for the majority. Africa is in a prime position to benefit from capitalism while avoiding the pitfalls that have befallen older societies.

Human civilisation has been through many changes. Despite these changes, however, progress itself was slow. For centuries, life went on, for most, people, just as it had always done. There is now the sense, though, that time is somehow speeding up. That the world, society, technology and economics are transforming at a disorientating rate. But what is the driving force of that transformation?

The scientific revolution gave rise to the industrial revolution. Engineers became entrepreneurs. But entrepreneurs need capital and it was the ability to raise capital that, among other factors, saw great leaps forward in society as its existing structures were shaken up and a new type of person was allowed to make their way to the top.

Since then, the world has seen many ideologies come and go. Political and economic experiments performed on grand scales, such as what passed for communism in the former Soviet Union, failed to bring about the emancipation of the poor, and the dream of the individual to be free of the yeoman yoke remained a distant one.

However, since the end of the Second World War, wherever capitalism has touched, dramatic changes have followed. No one would ever claim all those changes were for the best. Nor would you find many who would make the case capitalism is nothing but a benevolent force. But however you feel about the current economic system of choice, it is undeniable that capitalism has the power to transform in ways that no other economic idea has.

It is, of course, a difficult task to eulogise about capitalism these days. In the last few years, trillions of dollars have been traumatically lost from the world’s economy. Millions have been made unemployed and austerity measures imposed by governments have caused hardship and have been resented as punishing those who were not to blame for the crisis.

Africa has been largely insulated from the events which brought so many mighty economies to their knees, however. And now that new laws and regulations designed to curb the worst excesses of the banking sector are being drawn up in Europe and the US, the same sector in Africa remains open, keen to attract foreign investment and to support entrepreneurship as a means toward poverty alleviation.

Africa is following a well-trodden path. When India shook off foreign imperialist rule and eventually embraced free market capitalism, its economy began to grow.

Alongside that growth came a rise in life expectancy. The same happened in China where a sharp downward spike in economic growth that was caused by the failed experiment of central economic planning was reversed by a gradual liberalisation of the economy.

Those two countries are projected to overtake the economy of the US in the next few decades. That is, after centuries of low average income and poor health, it was the turning to free market principles of capital and entrepreneurship that set them on a course to health and prosperity.

The evidence that rapid change is already occurring is easy to find. Naturally, these cannot be attributed to just one cause, but to several. They all have something in common, though. They all rely on the general population being given the opportunity to fulfil their own potential.

Slowly, Africa’s post-colonial tyrants have died or been replaced, although a few are still hanging in amid an increasingly hostile environment. Stable government is now a common feature of many African countries.

The liberalisation of economies has led to privatisation and greater opportunities for entrepreneurs to provide services once the sole responsibility of governments.

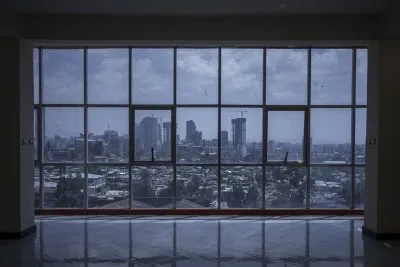

The subsequent urbanisation has allowed previously disparate members of societies to become connected. This has made governments more accountable to a greater number of people and weakened the traditional power bases of tribal leaders, which has profound implications for African society.

Capitalism has forced a change in the way business is done and with whom. Tribal chiefs have seen their power eroded as business transactions are conducted beyond the tightly controlled network of tribal allegiances, family and friends. The capitalist model forces you into relationships of trust with people you do not know, thus breaking centuries-old power structures.

It was those power structures that, among other concerns, both local and foreign investors found impossible to deal with but, now, are a diminishing problem. Countries in which such structures persist, are characterised by inefficiency, abysmal delivery, high costs, lack of competition, corruption, embezzlement and downright thievery, often on a grand scale. These countries are also often characterized by the presence of ‘palaces amid dung-heaps’.

History shows that when the common people wake up to the daylight robbery perpetrated on them by ruthless elites, they rise and are unstoppable. Today, more people than ever before are in a position to wake up, thanks to the mobile phone and social media.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google