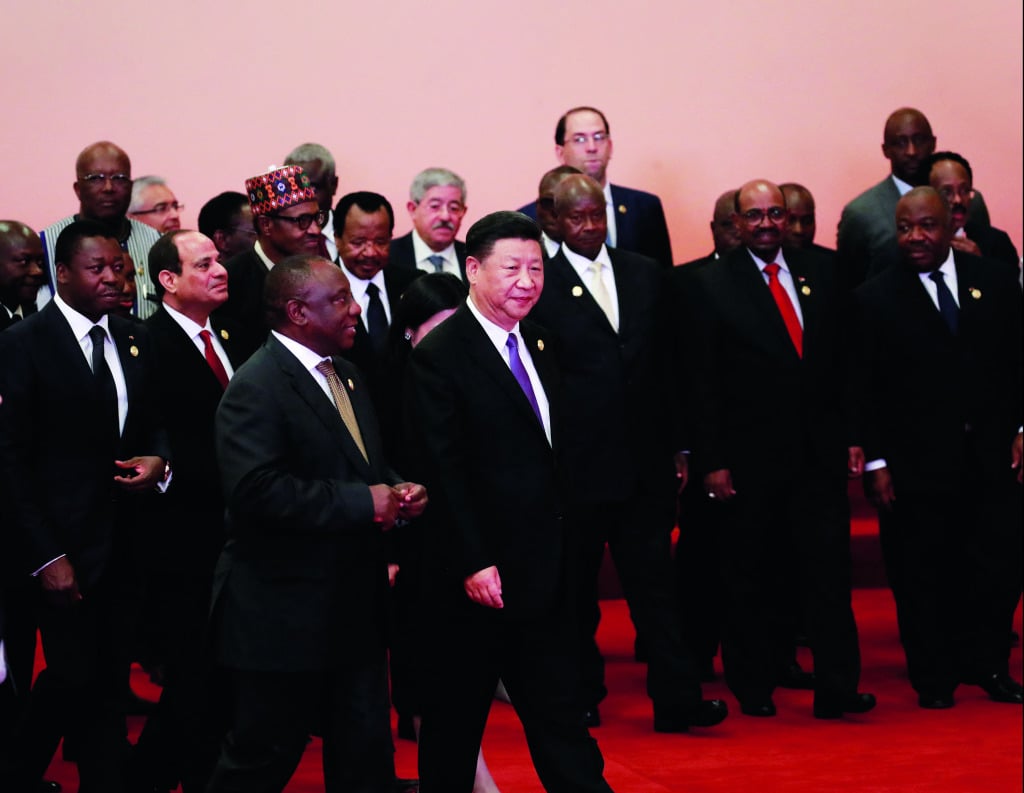

In September 2021, when the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) convenes, it will have been 20 years since it was first organised. Patterned after Japan’s Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD), it provides an organising mechanism for Chinese foreign policy toward Africa.

In the 20 years since the first FOCAC, the fortunes of Africa and China have radically diverged. The continent’s GDP has gone from around half of China’s in 2000 to one-fifth in 2020. In 2000, China’s GDP was one-tenth of US GDP.

Last year, total economic activity in China was $15.6 trillion, about 75% of US GDP, and the IMF estimates the figure will rise to 90% by 2025. In contrast, the combined GDP of Africa in 2000 was about $587bn, while today it is estimated at about $3 trillion.

Although these aggregate African GDP figures conceal substantial disparities between and within African states, the last 20 years have clearly been better to China than they have been to its African partners. As we begin a third decade of FOCAC summitry, there is an opportunity for the African side to reassess its relative position.

This FOCAC summit and the vast chasm that now exists between Africa and China should be an occasion for reflection on what it will take for Africa’s own hopes and aspirations to be fulfilled.

The courses charted by the two parties have yielded vastly different outcomes and the 20th anniversary of these meetings present an opportunity for African states to recalibrate and correct their courses using lessons from China’s past. I present below some recommendations on what Africa could learn from China’s spectacular rise.

Leadership matters

One cannot overstate the impact of leadership on the direction of any enterprise and there is much to learn from our Chinese partners about visionary leadership.

From Deng Xiaoping to all subsequent leaders of the Chinese Communist Party, there has been a relentless commitment to productivity and growth. There has always been a plan, revisited every five years, that charts their course. It provides structure to what they do and gives their governance purpose. Around these goals, they have forged myths and crafted narratives to convey and sell their vision to their fellow citizens.

These goals have defined how they engage with the rest of the world, the partnerships they form, and the policy choices they make.

In 2000, as now, China’s relationship with Africa was driven by China’s domestic context. Whether it was partnership with newly independent African states for their recognition of the People’s Republic of China over the Republic of China (Taiwan) at the United Nations, or in pursuit of African minerals to power Chinese growth in the 2000s, China has always had a plan in its engagement with Africa.

China’s quest for productivity and growth has driven its large-scale investment in human capital – including sending Chinese youth to Europe, Japan, and the United States. China’s acquisition of technology through outright purchase, cooperative knowledge transfer or corporate espionage, as well as its conduct toward allies and adversaries, has been driven by a clear domestic agenda.

Twenty years since the first FOCAC, it is clear which leadership team came to that meeting with a plan. It is thus imperative that African leaders returning to FOCAC understand that for their Chinese counterparts nothing is left to chance, and nor should it be for Africans.

Size matters

With a plan focused on improving productivity, China has used its population and vast physical size to its advantage. Africa’s landmass, collective population, and natural resource endowment should be advantages in engagement with others but has heretofore not been a benefit.

It is true that China has the added advantage of a continent-sized country and population under a single government, while Africa has had to manage 50-plus individual units, each driven by a different set of domestic imperatives. But this seems like a convenient excuse for the continent’s current crop of leaders.

Africa’s generation of political leaders post-independence had nowhere near the tools of coordination available to African leaders today, yet they understood the importance of acting as a unit. The Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was a fruit of their desire to do this. Many of them espoused an intellectual architecture that attempted to weave their history and culture into a purpose – pan-Africanism.

And while the OAU ultimately became a parody of its original intent, it was a good start. We are again presented with an opportunity to use Africa’s size to our advantage. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) could allow us to wield the power of a single market in a manner akin to what China has done over the last 20 years.

That a continent with over 50 votes in multilateral institutions is still incapable of substantively shaping the agenda is a tragedy. If we are to learn anything from our Chinese partners as we plan for FOCAC, it is that size matters.

Governance matters

Governance here refers to the structures and processes that guide how a country is run. It encompasses how decisions are made and how decision-makers are held accountable. Governance covers the state’s ability to provide public goods and how it either enhances or impinges on economic activity and actors. It describes the rules of the road; rules that are stable, predictable, knowable, and known.

Deng Xiaoping’s special economic zones were an example of governance. The rules of the special economic zones were designed to attract and keep foreign direct investment and encourage the diffusion of technology. By exempting these zones from taxes and various domestic rules, giving their chiefs and senior party officials broad latitude in adapting international best practices, these zones were set up to succeed. Their successes were later adapted to the rest of the country and their pragmatic approach presents a model for Africa.

Learning the lessons

These three overarching themes interacted to contribute to China’s rise from one of the poorest countries in 1978 to a peer competitor to the United States today.

As African leaders gather again at another FOCAC this year, it must be with the goal of ensuring that the next decade of Africa-China cooperation is characterised by better-than-average outcomes for the continent not only in its relationship with China but also with OECD members. With better leadership and better quality governance, we can wield Africa’s size as an advantage that enhances our negotiating position relative to our partners.

Gyude Moore is a senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development. He previously served as Liberia’s minister of public works.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google