Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been a shock to the world. As bombs rain down on Ukrainian cities, and our television screens fill with images of destruction, mass migration and sombre officials meeting in ornate rooms, businesses, governments and individuals across the globe are feeling the economic pain.

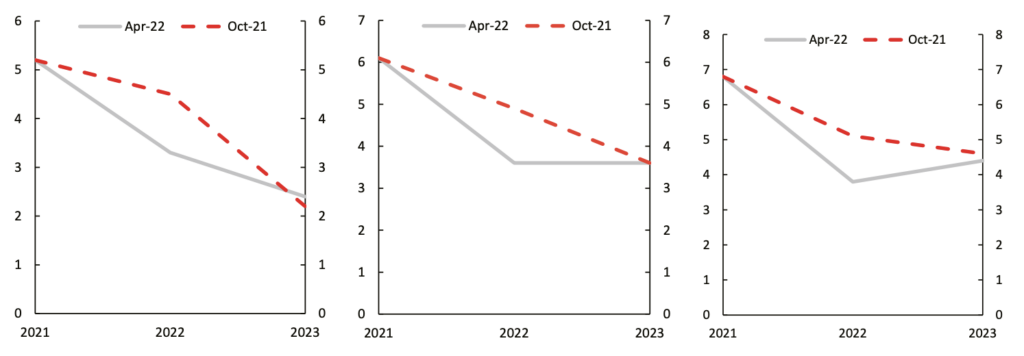

IMF figures, released on 19 April as part of the 2022 World Economic Outlook, give a sense of the magnitude. In the mere seven months since October 2021, when despite a military buildup on their shared border, outright war between Russia and Ukraine appeared inconceivable to most, the IMF have shaved 1.3% off their projection for world GDP in 2022 (see middle chart below).

The invasion has come at a difficult time for the global economy. The Covid-19 pandemic brought international trade and production to a standstill for almost two years, while governments in most parts of the world, faced with huge numbers of households and businesses teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, were forced to incur debt at levels unprecedented during peacetime.

How ironic that the recovery – fragile as it may have been – should now be derailed by a war.

Shocks through global economy

In truth, both Russia and Ukraine are minnows compared to the global economic powerhouses. At just $153bn in 2019, Ukraine’s GDP is somewhere between Sudan and Morocco, while Russia’s $1.6 trillion is roughly equal to Australia, just over half that of the UK and a fraction of the US’s $20.9 trillion. But when trying to unpick the outsized economic effects of Russia’s invasion, it is worth thinking about the ways in which shocks transmit through the globalised web of 21st century economic relations.

Commodity markets, thus far, have been the main channel through which the economic stress has travelled. Specifically the markets for energy – Russia is by far the major supplier of oil and gas to the EU – and food, with Ukraine and Russia together providing an outsized share of the global supply of basic agricultural goods such as wheat, corn and sorghum.

While energy has been getting most of the attention in more-developed countries, it is these rapid increases in food prices that are likely to hit the less-developed the hardest. According to the IMF, food accounts for roughly 40% of consumption spending for the average sub-Saharan African. In the EU, the figure is less than 15%. The longer the war continues and food prices remain elevated, the more Africans will be pushed into food poverty as a result.

This supply shock is compounded by the issue of elasticity; the speed at which demand and supply for commodities can adjust. While many countries hold substantial oil and gas reserves, and spare capacity amongst non-Russian suppliers such as Canada, the US, Saudi Arabia and some North African countries mean fuel supply can be rapidly expanded, already poor harvests and the lengthy period needed to cultivate new crops mean that food shortages are likely to endure well into 2023.

Rising debt puts African countries at risk

African governments incurred eye-watering levels of debt during the Covid-19 pandemic, with the African Development Bank (AfDB) reporting that the average African debt-to-GDP ratio is around 60%; a full 10 percentage points higher than it otherwise would have been. Moreover, a significant proportion of this debt is from a fractured set of commercial lenders, rather than traditional multilateral lenders such as the IMF and World Bank. Having accounted for just 17% of external African debt in 2000, private lenders now account for almost half.

These private lenders are more sensitive to market conditions than Africa’s traditional creditors. If the situation in Ukraine causes a global repricing of risk, then the African countries that owe them money may find these debts harder to service. When considered alongside the likelihood of widespread monetary tightening, as central banks across the world battle the inflation and volatile international capital flows that have been unleashed by the war, there is a real danger that the most heavily indebted amongst them could slip into default.

No wonder the AfDB is warning of another “lost decade” for African development.

This article originally appeared in the IC Intelligence publication Implications of the invasion of Ukraine for Africa.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google