Ten years ago, I travelled to Ethiopia for business. While I had visited Ethiopia several times before, I recall this trip vividly. At the time, the international narrative was of how Chinese workers were everywhere in Africa.

One morning, having breakfast at the popular Hilton Hotel (government budgets would not stretch to cover accommodation at the 1998-built Sheraton Hotel nearby) I was reading the local newspapers and saw on the front page a government press release setting out a “five-year schedule” for how Chinese workers would gradually decrease and local employees increase on one of the major infrastructure projects.

It was one of the first examples that piqued my interest in the nuances of Africa-China relations, and in particular in the idea of working strategically with this important country.

Fast forward 10 years, I am now thousands of miles away in Asia and my Beijing-based firm Development Reimagined has just published what we’ve called a blueprint for an African “China strategy”. And it has everything to do with that five-year schedule I read about that quiet morning in Addis.

Lessons from FOCAC

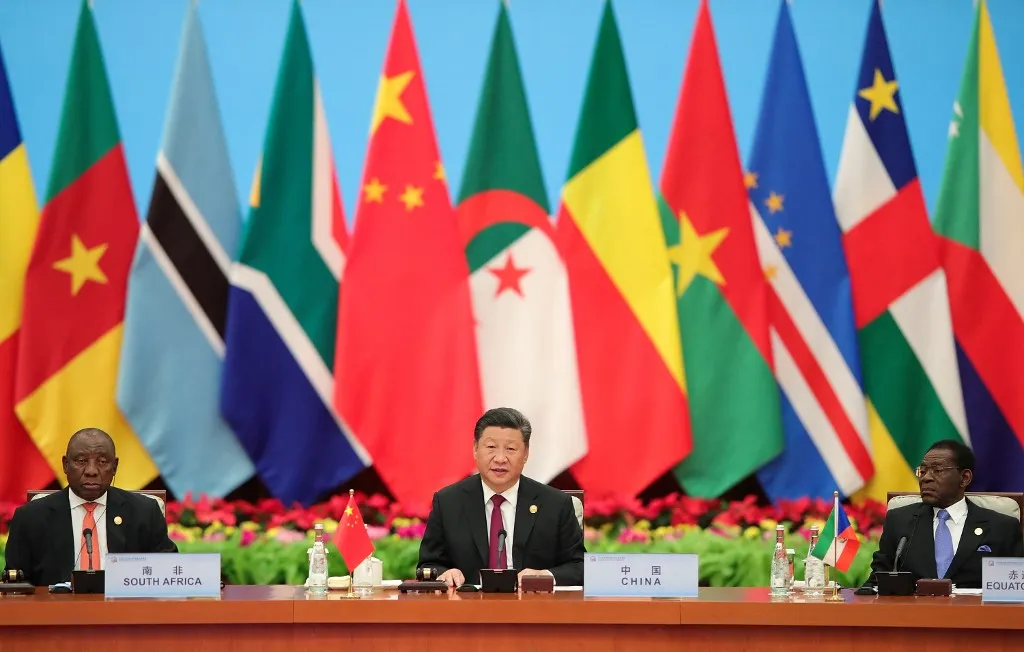

By 2011, a coordination meeting of Chinese and African Foreign Ministers – known as FOCAC – had been running for just over 10 years. It met triennially, and in 2006 it was “upgraded” to summit level, attracting numerous African heads of state.

It is safe to say the Chinese side was always more organised than the African side. To give just one example, in 2012, the African Union was formally brought into FOCAC, recognising its crucial role on the continent. Three years thereafter, China set up a specific representative office in Addis Ababa to nurture the AU relationship. But it was only in late 2018 – a further three years on – that the African Union’s representative office finally opened in Beijing.

In other words, the China-Africa relationship has so far been very much “China-Africa”, rather than “Africa-China”. That said, this is not unusual when it comes to African foreign policy. It is very often others who set the agenda. International meetings convened by think-tanks, academics and international organisations constantly ask “What should the US policy be towards Africa?”, rather than the other way: “What should Africa’s policy be towards the US?”

An urgent shift is needed in Africa-China relations

But back to China. Is it audacious to try to turn the China-Africa relationship around – to focus more on what Africa wants from China rather than the reverse? Does it matter, and is it even possible? Does the continent have sufficient bargaining power and, perhaps more importantly, collective will to do so?

I and my colleagues believe it is simply urgent and necessary to make this shift. I’ll illustrate with some examples.

In order to arrive at the strategic recommendations in the “blueprint”, we benchmark the Africa-China relationship in three different ways.

We benchmark it against Africa’s relationship with other development partners such as the US, UK and France; we benchmark it against China’s relationship with Asia; and we also benchmark it against the African Union’s seven continental frameworks – covering everything from infrastructure to agriculture to mining and tech and innovation.

We also summarise the findings of a comprehensive, 60-question survey of select African ambassadors to China – seeking their views on everything from how important they think it is to negotiate better on the terms and conditions of Chinese loans to how easy it is for their citizens to do business in China.

Overall, while China does come out ahead of most other bilateral development partners on several broad parameters such as trade, loans and student numbers, and seems to be steadily catching up in others such as investment and tourism, there are gaps.

For instance, China lags behind other development partners in the proportion of non-agricultural or mining products imported from Africa at only 16% – versus 40% or more by several others – likely due to higher Chinese tariffs on African consumer goods.

However, benchmarking against the rest of Asia reveals the real potential of the relationship. While proximity counts for a lot, what Asia demonstrates is that even low-income countries can get a great deal substantively from the China relationship – from outsourced Chinese factories providing thousands of jobs in Vietnam and Bangladesh, to Chinese tourists in Thailand, to transparent Chinese aid in Cambodia. Taking the metric of shares of non-agriculture or mining product imports for instance. Africa’s 16% compares to Asia’s 79%.

Finally, once we take an African perspective and ask “Is China meeting AU goals?”, we see that Africans should ask for more. The fact that, for instance, the 2018 FOCAC outcomes were designed around “eight major initiatives” rather than Agenda 2063’s six continental frameworks in the First Ten Year Implementation Plan speaks volumes.

Indeed, only two of those frameworks – on agriculture and science and technology – are mentioned in the 2018 action plan. We even explore whether a new China-Africa Free Trade Area would be beneficial or detrimental to the AfCFTA.

Towards a collective approach to China

It is these key, cross-continental African goals that drive the recommendations we make in the Africa-China strategy. Governments can also use the continent-wide strategy to develop more specific country-based versions. Fundamentally, our hope is that the Africa-China strategy will provide the basis for African leaders to express more agency vis-à-vis China, and even others, and that Africa will take a more organised, collective approach to engagement, in particular at the eighth edition of FOCAC, expected to convene in Senegal in late 2021.

Back in 2011, I saw that Ethiopia was using its domestic goals for creating local jobs alongside new infrastructure construction as a basis to negotiate for that unique five-year schedule. If that was possible 10 years ago, it’s surely possible now that China-Africa can shift to become Africa-China.

Hannah Ryder is the CEO of Development Reimagined, a pioneering African-led international development consultancy based in China.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google