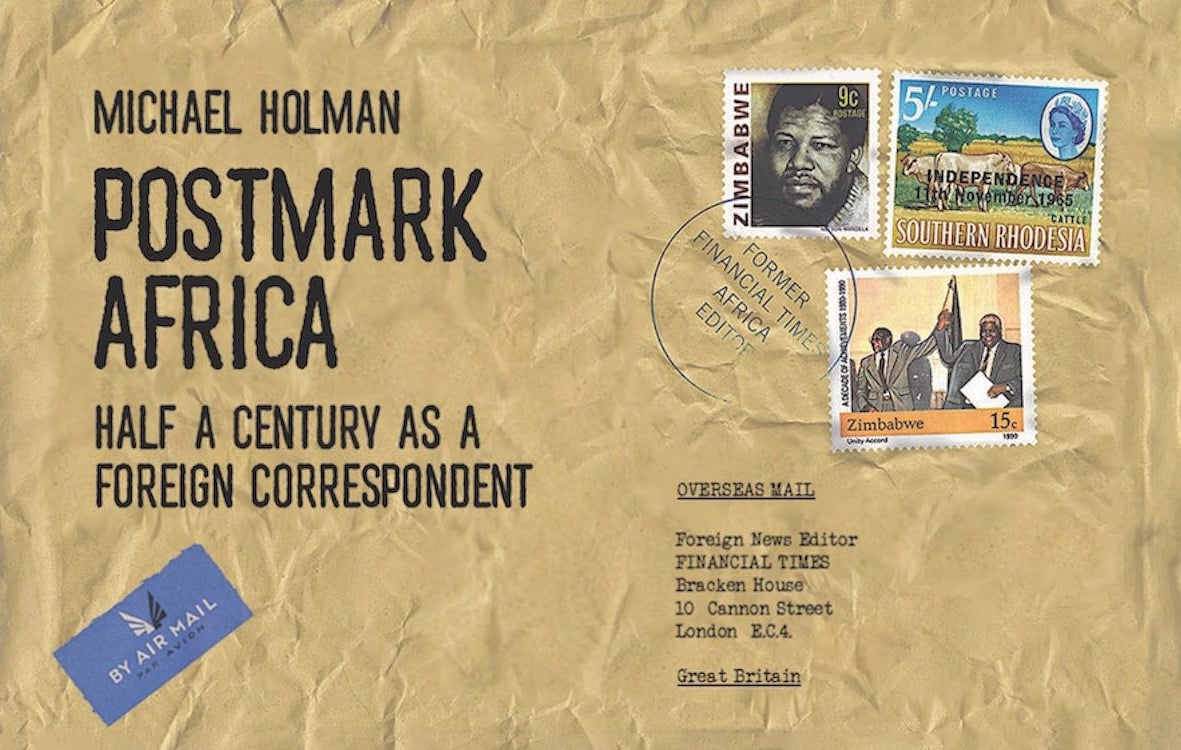

The role of Africa editor at the Financial Times offers a ringside view of the economic, political and social events shaping a dynamic continent. It is a role that Zimbabwean-raised Michael Holman, one of the most respected journalists of his generation, embraced with a passion from 1984 to 2002.

In this book, which reprints some of the veteran’s finest work after decades of covering the continent, we get an insight into the ideas and values that drove Holman from a dusty childhood in Southern Africa to the newsrooms of London.

Holman recalls his vibrant childhood in small-town Southern Rhodesia in the 1950s as “a combination of Arthur Ransome and Scouting for Boys with the innocence of the Famous Five”.

Innocence perhaps, but with a healthy dose of mischievousness. One of his pastimes was throwing stones onto corrugated tin roofs, provoking neighbours to shake their fists and remonstrate as the giggling culprit and his friends beat a hasty retreat.

But in a country as racially divided as Southern Rhodesia, the innocence of youth could not last. Holman noticed early on the divisions and prejudices that white Rhodesians nurtured not only towards the black Africans that comprised the country’s majority, but towards others of European descent.

“I was struck by the almost contemptuous way English-speaking Rhodesians treated Afrikaans speakers, who shared the lower rungs of the white Rhodesian class structure, together with Greeks and Portuguese,” he writes.

Defying Rhodesia’s white government

As decolonisation reached Africa and racial tensions heightened in the aftermath of Southern Rhodesia’s illegal Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) from the UK in 1965, Holman was increasingly drawn towards analysing his home country at a time when dissent towards the Rhodesian government was far from welcome.

Holman’s September 1964 broadside in the Bulawayo Chronicle, questioning prime minister Ian Smith’s practice of banning newspapers and political parties, showed the bravery and inquisitiveness that would drive his career in journalism.

“For while the rights of the white minority should be protected, this same minority has not the right to impose its wishes on four million Africans and still claim to represent what Mr. Smith calls a ‘democratic system’,” the young Holman wrote.

His early career coincided with historic events in Zimbabwe and the wider Southern African region, which come to assume a central role in the story. An article written for The Scotsman in 1971 titled “Apartheid, Rhodesian-style”, is a powerful indictment of the policies of the Rhodesian Front government and the segregationist tendencies that he argued increasingly mirrored those implemented south of the Limpopo.

A letter to friends in London in 1974 shows his deft treatment of controversial issues affecting his homeland, ranging from the Rhodesian Front’s refusal to grant black farmers the right to organise an effective labour union; relations with the new UK Labour government under Harold Wilson; and the growing military threat posed by the liberation movement.

Interviews and profiles of leaders of the liberation movements feature prominently, including a typically forensic analysis of Robert Mugabe, the rising force in nationalist politics who would come to dominate the country for decades with an iron fist.

Holman never shirked from describing the brutal conduct of the Rhodesian army in attempting to restrain the liberation movement through the use of brutal interrogation methods and torture, including waterboarding.

Yet even his criticism of the army didn’t save him from Rhodesia’s draft regulations as the white government increasingly demanded conscripts to fight its losing war against nationalists. Holman shares a surreptitious recording that he made in 1977 of his military exemption board hearing, a last ditch effort to avoid the draft. It failed, and he fled to the UK.

Beyond Zimbabwe

While painful, this exile may ultimately have been a blessing in disguise, helping to shift Holman’s journalistic gaze beyond his native Zimbabwe. In subsequent years, Holman developed an unerring knack for being present at some of the continent’s most dramatic political events.

Whether meeting Hastings Banda, the eccentric president of newly independent Malawi; recalling the charisma of Tanzania’s President Nyerere; or analysing the fraught bargaining in Geneva between representatives of President PW Botha of South Africa, Cuban leader Fidel Castro and President Eduardo dos Santos of Angola over the settlement that heralded independence for Namibia, Holman was witness to an exciting era of massive upheaval and outsized personalities.

Beyond the politics, exciting travel stories grip the readers’ attention. Africa’s chaotic urban environments and stunning vistas are memorably rendered, from the bureaucratic complexity of Nigeria to the “heat, humidity, atmosphere and anarchy” of Zaire, later DR Congo.

A humane voice

And while the life of a newspaper foreign correspondent might be deemed enviable, an endless round of five-star hotels, first-class air travel and gala receptions it is not. In an amusing chapter, “Ideas of Luxury”, Holman disabuses the reader by describing some of the more dubious facilities that he has been forced to use during his travels.

It is a witty counterpoint to the tragic and disturbing episodes of African life that he witnessed over the last few decades.

This collection, balancing the deadly serious and the humorous, is testament to an eloquent, humane voice who chronicled some of the most turbulent and consequential years in the continent’s modern history.

Want to continue reading? Subscribe today.

You've read all your free articles for this month! Subscribe now to enjoy full access to our content.

Digital Monthly

£8.00 / month

Receive full unlimited access to our articles, opinions, podcasts and more.

Digital Yearly

£70.00 / year

Our best value offer - save £26 and gain access to all of our digital content for an entire year!

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google